Ebola outbreak: A public health emergency

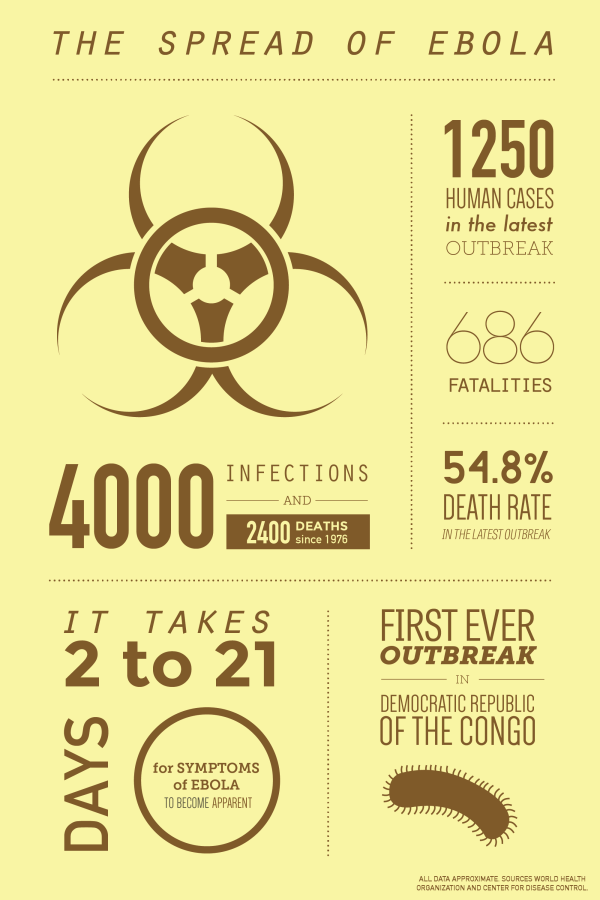

The latest outbreak of Ebola, spanning African countries Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, started in March and has progressed to an official human case count of nearly 1300, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Ebola virus disease, otherwise known as Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF), is contracted through intimate contact with the blood or bodily fluids of infected animals, and is then spread through humans by skin-to-skin contact with infected individuals. The World Health Organization fact-sheet lists symptoms such as acute fever and the typical common cold symptoms, vomiting, diarrhea, rash, impaired kidney and liver function, and in some cases internal and external bleeding.

On Aug. 8, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) by the World Health Organization. Two American Ebola patients were taken from Liberia to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta and received treatment for the disease in one of the four U.S. units capable of securely containing the infectious disease. They were released on Aug. 22.

Dr. G. Marshall Lyon, an Assistant Professor of Medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Emory University School of Medicine, shared his insights on the situation in an email interview with the Winged Post.

“The recommended therapy for patients suffering from Ebola is one of supportive care,” Dr. Lyon said. “I would press upon future physicians caring for patients that aggressive supportive care is the best chance to help patients survive an episode of Ebola virus disease.”

The Ebola virus specifically targets blood clotting cells, which leads to uncontrollable bleeding. The virus also damages the immune system and organs.

Lyon does not believe that the threat of Ebola is significant enough to trouble the developed world.

“Typically Ebola happens in outbreaks over a limited period of time, and then months to years pass before another outbreak happens,” Lyon said. “The strains of Ebola which infect humans naturally occur only in Africa. In my opinion I think it’s only a matter of time after this outbreak ends before another one comes along. Our healthcare standards are much, much better than what is currently available in sub-Saharan Africa. And, that healthcare system is much more accessible than most of Africa.”

Aadyot Bhatnagar (12) is currently working on a Mitra grant paper on the efficacy of malaria control policies in Tanzania, which according to him made him read academic literature on the interactions of past Ebola outbreaks with the infrastructures of presently afflicted countries.

“I believe that the history of malaria control can teach us some more general epidemiological lessons about controlling the spread of infectious diseases in developing countries,” Aadyot said. “Prime among these themes are the need for better-equipped hospitals at the community and village level, improved access to health workers, and more effective ways to educate the public on how to avoid infection.”

Aadyot was also dismissive towards the idea that the Ebola virus would become a catastrophic illness because of its detection at an early stage as well as its limited ability to infect new patients, being fluid-borne.

“As the climate is changing around the world due to global warming, it is very possible that the severity and ranges of these types of diseases may change significantly,” Upper School Biology teacher Dr. Matthew Harley said. “My guess is that there will be large fluctuations in the severity of this disease but that it will remain fairly well contained geographically for at least the next few years.”

The difference between Malaria and the Ebola virus lies in how both are spread. While Malaria is vector-borne, Ebola is usually transferred from person to person. Controlling the vector in Malaria’s case is a simple way of combating the disease; the lack of a vector makes the Ebola virus more difficult to contain but also more difficult to contract.

Those who survive the Ebola virus acquire antibodies to the virus and are immune to future disease from the virus, which indicates that a vaccine is possible though still expensive.

This article was originally published in the pages of The Winged Post on August 29, 2014.

Elisabeth Siegel (12) is the editor-in-chief of the Winged Post. This is her fourth year in Journalism, and she especially loves production nights and...

Shay Lari-Hosain (12) is the Editor-in-Chief and co-founder of Wingspan Magazine. Shay has interviewed 2013 Nobel Laureates, authors like Khaled Hosseini...

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)