App to assist the emerging markets of India

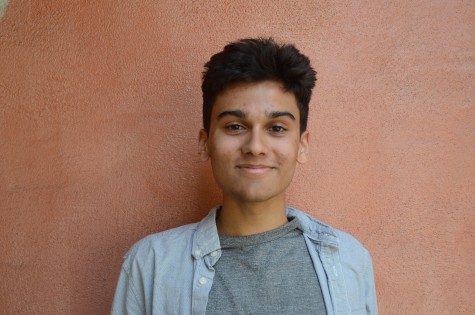

The Egyptians certainly didn’t anticipate what recent Stanford graduate Govinda Dasu (Harker ’12) would do with their Rosetta Stone.

Govinda sought to find out if translation software Rosetta Stone could be used to teach English to an individual with no prior background. He documented the experiment in order to write his own, specialized smartphone application, which would improve upon the weaknesses of Rosetta Stone in context.

“You have to make it less boring. Rosetta Stone is kind of like a classroom,” Govinda said in a video interview from Hyderabad, India with theWinged Post. “She really always wanted to watch YouTube videos a lot more than she wanted to do Rosetta Stone.”

Govinda referred to his subject Geeta, a 37-year old illiterate cook living in Hyderabad who completed approximately 20 hours of Rosetta Stone. He explained how knowing English is a valuable asset in the emerging markets of India, citing transport service Über as an example.

Govinda pointed out that Rosetta Stone is targeted at the developed market; however, the greatest demand for learning a new language lies in the developing market. He also noted shortcomings of the subject’s experience with the methods of learning the software employed, as well as her technical difficulties maneuvering the interface.

“[It] was difficult was for her to be able to understand grammar. She was really good at understanding nouns, adjectives, even verbs,” he observed. “But at the point of conjugating pronouns, ‘their ball’ vs ‘her ball’, she couldn’t understand at all what was going on. Grammar was a no, vocabulary was a yes.”

During the course of the experiment, Govinda also noted that incentivizing the software was effective in engaging Geeta’s interest.

“She was always concerned with how many points she had,” he said. “You have to balance that with not making it so competitive that you have a leaderboard and she always feels like she’s at the bottom of the leaderboard, if you make it connected to social media or contacts on her own phone.”

Govinda explained his business model, which will continue to generate revenue for ongoing support. The software will enable more low-income groups to secure higher-level jobs while it proffers itself as a recruiter to businesses.

“[I plan to] make it free for people to learn English using [the] software, but charge the grocery stores and the Übers and hotels for a conversation with our English graduates to make their process of recruiting a little bit easier,” he said.

To maximize accessibility, the application will be written in HTML5 and eventually Java, meaning it will run on smartphones and desktops, as well as the more ubiquitous feature phone. He does not expect many desktop users.

He hopes to eventually implement the program in Indian schools, which will offer a larger number of prospective users.

The Egyptians certainly didn’t anticipate what recent Stanford graduate Govinda Dasu (Harker ’12) would do with their Rosetta Stone.

Govinda sought to find out if translation software Rosetta Stone could be used to teach English to an individual with no prior background. He documented the experiment in order to write his own, specialized smartphone application, which would improve upon the weaknesses of Rosetta Stone in context.

“You have to make it less boring.” Govinda said in a video interview from Hyderabad, India with theWinged Post. “She really always wanted to watch YouTube videos a lot more than she wanted to do Rosetta Stone.”

Govinda referred to his subject Geeta, a 37-year old illiterate cook living in Hyderabad who completed approximately 20 hours of Rosetta Stone. He explained how knowing English is a valuable asset in the emerging markets of India, citing transport service Über as an example.

Govinda pointed out that Rosetta Stone is targeted at the developed market; however, the greatest demand for learning a new language lies in the developing market. He also noted shortcomings of the subject’s experience with the methods of learning the software employed, as well as her technical difficulties maneuvering the interface.

“[It] was difficult was for her to be able to understand grammar. She was really good at understanding nouns, adjectives, even verbs,” he observed. “But at the point of conjugating pronouns, ‘their ball’ vs ‘her ball’, she couldn’t understand at all what was going on. Grammar was a no, vocabulary was a yes.”

During the course of the experiment, Govinda also noted that incentivizing the software was effective in engaging Geeta’s interest.

“She was always concerned with how many points she had,” he said. “You have to balance that with not making it so competitive that you have a leaderboard, and she always feels like she’s at the bottom of the leaderboard, if you make it connected to social media or contacts on her own phone.”

Govinda explained his business model, which will continue to generate revenue for ongoing support. The software will enable more low-income groups to secure higher-level jobs while it proffers itself as a recruiter to businesses.

“[I plan to] make it free for people to learn English using [the] software, but charge the grocery stores and the Übers and hotels for a conversation with our English graduates to make their process of recruiting a little bit easier,” he said.

To maximize accessibility, the application will be written in HTML5 and eventually Java, meaning it will run on smartphones and desktops, as well as the more ubiquitous feature phone. He does not expect many desktop users.

He hopes to eventually implement the program in Indian schools, which will offer a larger number of prospective users.

The Egyptians certainly didn’t anticipate what recent Stanford graduate Govinda Dasu (Harker ’12) would do with their Rosetta Stone.

Govinda sought to find out if translation software Rosetta Stone could be used to teach English to an individual with no prior background. He documented the experiment in order to write his own smartphone application, which would improve upon the weaknesses of Rosetta Stone in context.

“You have to make it less boring. Rosetta Stone is kind of like a classroom,” Govinda said in a video interview from Hyderabad, India with theWinged Post.

Govinda referred to his subject Geeta, a 37-year old illiterate cook living in Hyderabad who completed approximately 20 hours of Rosetta Stone. He noted shortcomings of the methods of learning the software employed, as well as the subject’s technical difficulties maneuvering the interface.

“[It] was difficult was for her to be able to understand grammar,” he observed. “Grammar was a no, vocabulary was a yes.”

The software will enable more low-income groups to secure higher-level jobs while it proffers itself as a recruiter to businesses. To maximize accessibility, the application will be written in HTML5 and eventually Java, meaning it will run on smartphones and desktops, as well as the more ubiquitous feature phone.

He hopes to eventually implement the program in Indian schools, which will offer a larger number of prospective users.

This article was originally published in the pages of The Winged Post on August 29, 2014.

Riya Godbole is the Lifestyle Editor of The Winged Post. She is a senior and has been part of the journalism program since her freshman year. Her favorite...

Shay Lari-Hosain (12) is the Editor-in-Chief and co-founder of Wingspan Magazine. Shay has interviewed 2013 Nobel Laureates, authors like Khaled Hosseini...

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)