Labs and demonstrations ignite enthusiasm in students

“And 3…2…1!” Boom.

These are not the sounds you would normally hear in any sort of academic setting, but an exception arises in the form of science classes at the Upper School—more specifically, chemistry classes.

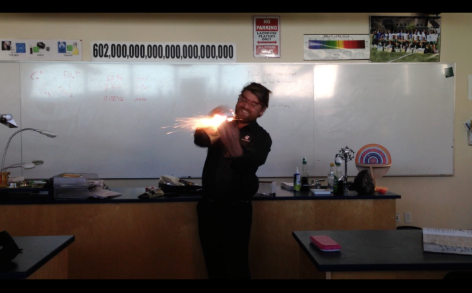

Demonstrations and labs are commonplace in science classrooms, even when they tend to be on the more dangerous side for added effect. Chemistry teacher Andrew Irvine uses a variety of demonstrations ranging from reacting thermite to making samples of contact explosive nitrogen triiodide to engage students and promote enthusiasm.

“Nobody gets hurt in my classroom, because the environment is excessively safe,” Irvine said. “It’s a way to get that ‘what-if’ out of the system of the student so that we can [see] what would happen in [my] safe setting. I’m the chemistry teacher, so I have a certain responsibility to take care of that intellectual curiosity.”

Many students favor these more daring choices of curriculum because of the added hands-on opportunities.

“It makes the class so much more interesting,” said Kurt Schwartz (10), a current student in Irvine’s class. “The class is actually involved in learning because they see practical uses of it, so more interest in the class would help students pay attention and stay awake.”

According to Irvine, accidents have been infrequent throughout all of his classes, but he remembers one in particular during his first year teaching at Harker.

“The most dangerous experiments are probably the alkali metals. When you put them into water they react violently. I do it outdoors now, because the first year I did it indoors in Dobbins, and it went up, hit the ceiling, bounced off the ceiling, and landed on some kid’s head and some girl’s blouse,” he said. “And it didn’t give them major injuries. It gave them a small little burn, but it was terribly scary as a new teacher.”

He also recalled an accident during his first year when he suffered second-degree burns on his hand while attempting a demonstration on his own. More recently, he and the Chemistry Club attempted a hydrogen explosion in a large water jug.

“If you let hydrogen mix with the air, you’ll get more surface area,” he said. “The reaction rate will increase, so instead of getting this large, concussive boom where the hydrogen is burning outside the bubble of hydrogen and eventually it burns into the middle, you’ll get a big gunshot sound because it’s so rapid.”

Another chemistry teacher, Robbie Korin, reflected on his own class’ experiences in demonstrations and labs. A notable demonstration he does for his chemistry students involves the melting and freezing of wax, causing the vapor above the wax to combust due to the exothermic reaction.

“We always do that as a demo, because it’s kind of fun to do,” he said. “For demonstrations, we keep the students back, and then we do it far enough away, and we have a safety shield that we can use if we need to.”

Other departments may not have the same explosive factors as chemistry classes, but biology teacher Michael Pistacchi stressed the importance of hands-on learning.

“When you are a scientist, you spend most of your time actually working with your hands […] so it’s pretty vital for students to spend a lot of time doing hands-on work,” Pistacchi said. “That’s the best way to interact with the material, to see how the structures work. You can talk about the respiratory system, but actually seeing the lungs is a key way to understanding what you’re doing.”

Other students still have fond memories of exciting science periods.

“All of the demonstrations were really fun,” Sophia Shatas (11) said. “We’re teenagers. We thrive on close danger experiences, even though we know that we’re safe, so I think it just adds excitement and makes it interesting.”

Students can also join the Chemistry Club for further exposure to chancy demonstrations and experiments.

This piece was originally published in the pages of the Winged Post on March 12, 2014.

Elisabeth Siegel (12) is the editor-in-chief of the Winged Post. This is her fourth year in Journalism, and she especially loves production nights and...

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)