Statistically slim odds of winning did not daunt senior Ashvin Swaminathan. He coolly accessed the list of Intel semifinalists in hopes of seeing his own name amongst the bevy of brilliant student researchers.

“It’s almost more nerve-wracking than the Harvard app,” he said, though his posture betrayed none of his nerves. His eyes were locked to the screen. He saw his name. His composure morphed into relieved ecstasy. He leapt into the air. Ashvin was one of only 300 in the nation experiencing the same reaction.

Ironically, his joy makes one picture the thousands of rejected applicants with dejected shoulders who now have to bear the disappointment of not being selected.

For some students who participate in competitions, like Ashvin, competitions can serve as pressure cookers for creative genius, ripe to be harvested in the pursuit of college, scholarships, and parental or personal glory. To others, however, the double-edged sword of competition also causes excessive anxiety and threatens to stifle creativity and individuality, especially in the classroom.

While our school advertises itself as a college-prep institution, some believe that the denotation threatens its students’ emotional well-being.

“The thing is, we should be a life-prep school,” said Juhi Muthal (10), who judges the submissions for the school’s literary magazine, HELM. “I’m very happy with the way that Harker teaches us how to think, but it makes students feel like they need to measure up.”

The shift to a more competitive mindset may be more recent than expected. Dr. Denise Pope, a senior lecturer at Stanford University, notices a wide generational gap in terms of acceptable coursework.

“When I was in high school, we didn’t have to take the top classes or cheat or slide through classes to get an extra point on our GPA’s,” said Dr. Pope, who co-founded Challenge Success.

This is the second year the Upper School has participated in the program, which informs Bay Area students and their families of the need to lead balanced lives.

“Nowadays, there’s a really hyper-competition about college. More people apply to college, which is great, but elite universities haven’t expanded their offerings,” she said.

On the other hand, student researcher Samyukta Yagati (10) sees college as only a small root of the competitive environment. She admits that comparisons between students sometimes propels them to achieve academic success.

“On a day to day basis, getting into college isn’t really immediate,” said Samyukta, who has won awards at the regional Synopsis science fair. “Day to day competition is more like ‘Oh, I did this well, but how did other people do?’”

In contrast, Ashvin claims to compete with only himself. He got into the competition circuit early when his fourth grade teacher gave him his first math contest, the California Math League (CAML) competition, on which he got a perfect score. The 2012 CAML was returned on January 10 to current third graders who were required to take it, perhaps hooking future mathematicians onto the thrill of competing.

“It’s honestly fun for me to do tough problems in a time constraint,” said Ashvin, who finds inspiration in his mathematician father and engineer mother.

To him, in fact, the Upper School should have a more competitive atmosphere.

“I thrive in competition. I’d actually like my classes to be more competitive, though it ultimately depends on the individual,” he said.

While Ashvin has been successful in terms of achievement, college counselor Martin Walsh does not see a correlation between competition and success, which “everyone defines differently.”

“You can’t define all success in terms of winning and losing. For me, success might be finally finishing Moby Dick, which I’ve been working on for eight months,” he said.

Sophomore Maya Nandakumar agrees with Walsh, believing that competition has a “net negative” effect on a person’s confidence.

“The competitive spirit definitely threatens your self esteem,” she said.

Dr. Pope identifies the stifling nature of the “competitive spirit,” which she credits with suffocating artistic and intellectual creativity as well as curiosity.

“If you look at what you have to do in most classrooms to get the A, you’re going to need to curb that creativity,” she said. “Part of the nature of creativity is risk-taking, and if you’re trying to get that grade or that spot, you’re not going to take that risk. And that continues into adulthood. What Silicon Valley CEO’s say is that people who are concerned about keeping their jobs or pleasing their bosses are less likely to think outside the box. Sometimes you have to be disruptive.”

When we were younger, the motivation to compete often lay in a physical reward. It was the possibility of a gold star, a trip to the local GameStop, or an extra dollar in allowance that propelled some to enter spelling bees and music competitions.

In high school, though, the incentives become far more abstract. The gold star becomes a college acceptance glinting in the future, and the shopping expedition transforms into parental hints and nudges to succeed. In order to procure those rewards, participants sometimes have to stifle their own creativity.

The Students as Content Creators (SACC) project is an ongoing series of articles that relate the process of young people producing their own ideas in various areas of business, science, art, music, theater, and more. Some stories also examine potential conflicts that may arise due to ownership issues.

The SACC symbol used in this article is a derivative of the trademarked Creative Commons logo.

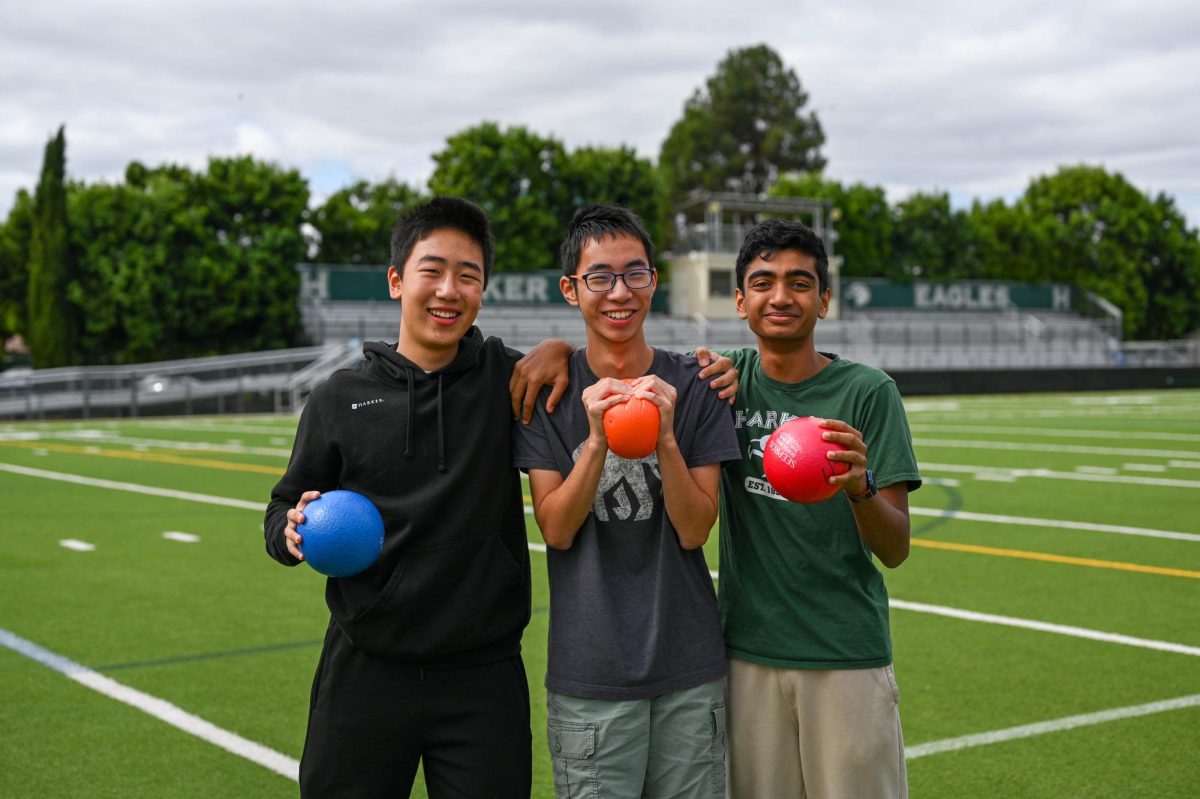

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)