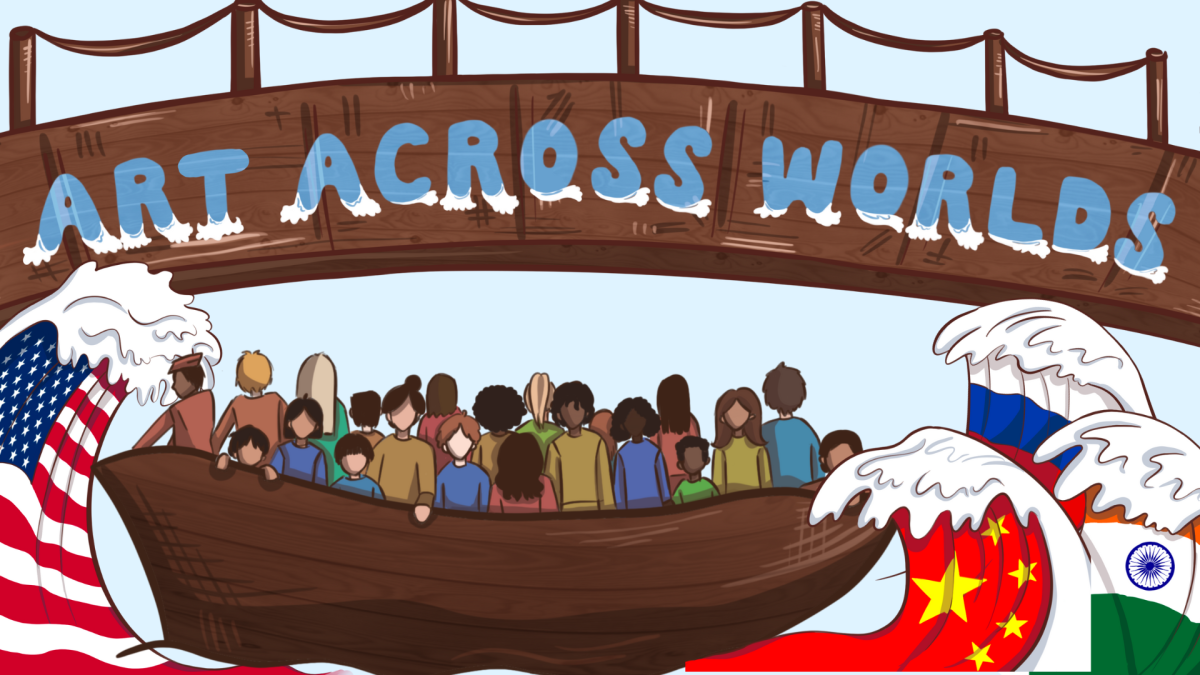

Pop culture isn’t just entertainment — it’s a measure of belonging. From inside jokes in classic sitcoms to chart-topping songs, American media signals who “fits in.” For immigrant youth, this raises a crucial question: how do you blend your heritage with the culture around you?

Junior Aanya Shah, the child of two Indian immigrants, feels this tension deeply. Aanya has come to navigate her feelings through art, finding a space where she can merge both her Indian roots and the American culture she experiences daily.

“I feel like I’m stuck between two worlds,” Aanya said. “At school, I don’t always relate to the things my peers talk about, and at home, I feel like I’m not fully connected to my family’s traditions. Art helps me create a space that is entirely my own.”

Aanya’s paintings blend traditional Indian motifs with modern Western influences, reflecting the two cultures that define her. Yet, she is acutely aware of the pressures to conform to one identity.

“I do feel like there’s an expectation to fit into certain boxes,” Aanya said. “It’s like you either have to completely embrace your heritage, or you have to be fully American. But I don’t think it has to be one or the other.”

Like Aanya, Vera Sorotokin, a sophomore whose Russian father and Ukrainian mother shaped her upbringing, also grapples with her dual identity. Growing up with these two cultural influences, Vera’s art became her tool for reconciliation.

“Through my work, I really hope to connect both sides of my family,” Vera said. “That’s been a long, long wish of mine because we’ve had so much conflict between the two sides in my family, too. So another goal for my paintings is to bring everyone together and eventually reach peace. I don’t know if that’s possible, but that’s my hope.”

Vera’s work embodies a deep longing for unity, drawing from both her Russian and Ukrainian heritage to foster healing through art. Yet, she also faces the challenge of bridging cultural divides that run deep in her own family, reflecting a broader struggle that many children of immigrants face.

Senior Iris Cai’s exploration of identity takes a different form — through poetry. Iris, who hails from a Chinese family, uses her writing to capture the complexities of her Asian American experience. Her poems often delve into the contrasts between the values of her family’s Chinese heritage and the American culture she navigates outside the home.

“The dynamic of being Asian American and interacting with my family members, which is one heritage, and going out into the outside world, which has a different culture — the tensions, but also the interplay between that really interests me,” Iris said.

In her poetry, Iris often includes pinyin, the romanization of Chinese words, to highlight the differences in language and meaning. This technique allows her to bridge the gap between her two worlds, showing how language and culture shape the way she sees herself.

“Sometimes I include pinyin in my poems, which is writing out Chinese words but in English characters,” Iris explained. “It’s a way of playing with language and showing how the same thing can carry different meanings in different contexts.”

Aanya, Vera, and Iris view art as more than just a creative outlet. Through their work, they challenge the notion that they must choose one identity over another, embracing both their heritage and the surrounding culture as integral parts of who they are.

For many children of immigrants, however, pursuing art isn’t always encouraged. In families where stability is prioritized, creative careers may be seen as impractical. The sacrifices of prior generations may influence youth from immigrant families to follow in their parents’ footsteps rather than breaking the mold.

“My family is all immigrants, and we’re grappling with the weight and also the partial loss of history that occurs when we migrate to a new land,” Iris said. “Family is really important, so sometimes conversations with my family members or relationships between us and the idea of loyalty or tradition versus following my own path influence me and my writing.”

One organization working to support young artists with immigrant backgrounds like Aanya, Vera and Iris is ARTogether, an Oakland-based nonprofit that provides art programs for immigrant and refugee communities. Through school partnerships, murals, festivals and mentorship, ARTogether recognizes that art is more than a hobby — it’s a means of self-definition.

ARTogether program director Michelle Lin recognizes that one of the biggest barriers to young artists isn’t just external — it’s internal. Many emerging artists struggle with self-doubt, questioning whether their work is valid.

“There are a lot of resources immigrant and refugee artists have additional obstacles towards,” Lin said. “They’re trying to figure out how to get started and deal with the internalized feeling of being illegitimate as an artist.”

Lin knows this struggle firsthand. As a poet, weaver and arts organizer, she recalls how her own artistic journey helped her embrace her intersectional identity.

“I help build spaces for folks to come together and support one another through art,” Lin said. “When I was younger, writing was very solitary. Then in college, I found a community with other poets and people of color. Poetry became a way to be in conversation with others.”

That shift from isolation to community shaped her work at ARTogether. She understands the emotional weight of being part of an immigrant family, where cultural expectations and personal identity don’t always align.

For Lin, resisting assimilation is an intentional act that requires redefining success beyond mainstream standards. She believes immigrant communities shouldn’t feel pressured to conform to a singular narrative, especially one that erases their unique cultural histories.

“I’m not interested in aligning myself with a white-dominant narrative,” Lin said. “When I say I’m against assimilation, I mean I’m against being folded into something that divides communities of color. A lot of my work is around my experiences as a queer, estranged child of immigrants, particularly as an Asian diasporic person. I think about how to build a life here while staying connected to my heritage.”

Instrumental music teacher and composer Jaco Wong advises several students as they compose their own pieces. He recognizes that many students wish to represent their cultural stories, having written his own pieces revisiting his experiences from his childhood in Hong Kong. In AP Music Theory, he teaches students about the language of music: how it serves as a backdrop for personal expression and transcends cultural boundaries.

“Music is really powerful in society,” Wong said. “Not all music is cultural, but when it is, it could add so much color to what you’re experiencing in life and listening to. That’s the beauty of it — music itself, it’s kind of a neutral medium. Composers and listeners decide to do whatever they want with it, and that can be really powerful.”

In a world that often forces youth with immigrant backgrounds to choose between their heritage and their surroundings, art offers a space where they don’t have to choose at all. Through artwork, young artists can explore different ideas of home and belonging and reconcile the parts of their identity.

“Home can take on different meanings,” Iris said. “There’s the literal home of being in your physical house with your family around, and there’s the idea of homeland, where your family is originally from. You can also feel at home in different places with different people. For me, home is like a combination of all three. I would say that culture is a backdrop or a lens in which to view my writing.”

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)