In the midst of the winter season, the age-old debate between real and artificial Christmas trees surfaces yet again: the nostalgic scent of pine and rustic charm of a real tree versus the glossy, truly evergreen bristles of a synthetic lookalike.

Beyond the aesthetics, however, lies a narrative of sustainability and ecological impact that provides the basis for a greener winter. In a world increasingly conscious of environmental footprints, it’s time to unravel the surprising truth: real Christmas trees are the more eco-friendly choice.

In the U.S. alone, 10 million artificial Christmas trees are purchased each year. While it seems like metal and plastic conifers protect the environment by preventing the need to plant and cut down trees, in reality, it is just the opposite.

Upper School Green Team member Stella Yang (10) noted that while the artificial trees are more easily accessible, they are an unsustainable option in Christmas decorations.

“A lot of families prefer buying artificial Christmas trees because they are cheaper and last longer,” Stella said. “But the downside is that they are made entirely of plastic, which, of course, isn’t great for the environment. The greener option would be to buy real Christmas trees. Plus, they smell great!”

Due to their unsustainable manufacturing techniques which lead to greenhouse gas and toxic chemical pollution, in order for a fake tree’s environmental impact to be lower that of a real evergreen, households must use them for more than ten years. This contrasts the average of six years it takes for families to replace their artificial tree with a new one. Bringing to mind images of mass deforestation, it seems unintuitive that watering and cutting down seven-foot-tall spruce trees by the million could be beneficial to the environment.

Upper school faculty sustainability committee member and Green Team advisor Diana Moss leads various initiatives to improve sustainability around the Harker campus. Moss reflected on the surprising environmental impacts of artificial Christmas trees.

“What we know is that the real trees are actually more sustainable,” Moss said. “It’s funny because about 20 years ago, my husband and I had a family tradition of going to cut a tree up in the Santa Cruz mountains and it was really fun. And then we thought, ‘We don’t like cutting down trees. It feels, not right,’ so we bought ourselves an artificial tree that we’ve had for 20 years. Now that I know more about manufacturing and production of things that have to be shipped long distances with transportation, I realized that I would have been better off not to buy the artificial tree and get fresh ones.”

While live Christmas trees need large amounts of water to grow, 79% of trees come from small-scale farms in places like Oregon, and North Carolina, where water is plentiful and farmers can rely on nature to water their plants.

Furthermore, it takes an average of seven years for the evergreens to grow to a marketable size, so not all the trees on a farm can be harvested each year. For every tree that is sold, nine more continue to mature, recycling air, purifying groundwater, stabilizing soil and providing habitats for animals.

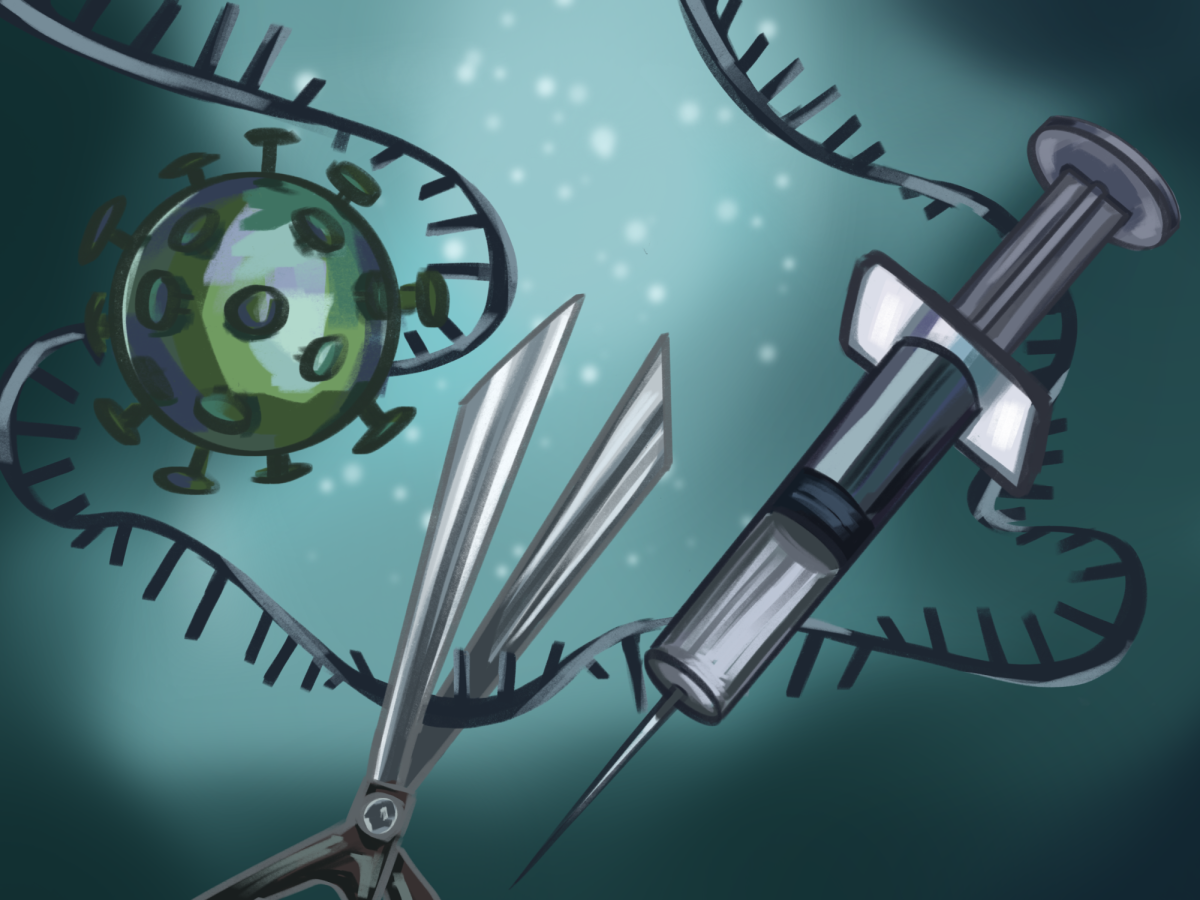

Whereas live trees absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, artificial trees contribute to greenhouse gas pollution. The majority of artificial Christmas trees are made of polyvinyl chloride (PVC), which not only requires huge amounts of fossil fuel energy to produce but also contains harmful toxins that pose serious health risks.

PVC production releases huge amounts of dioxins, which are one of the most detrimental chemicals to human and environmental health due to their persistent nature. Entering the food chain through contaminated water and aquatic organisms, dioxins are easily absorbed and stored in fat tissue, where they build up in animals. Humans can then be exposed to the chemical through meat, dairy, fish and shellfish, and develop a risk of several types of cancer including lung and liver, and developmental problems especially among fetuses.

Due to their material composition, artificial Christmas trees cannot be recycled or broken down, furthering the environmental impact of each tree. Moss added that while the trees can last for many years, most families end up discarding them after only a short period of time.

“They just end up in our landfill and that’s a bummer,” Moss said. “If you have a live tree, it can be chopped up and mulched and that’s good stuff that can go back to the earth. The trees are made in China, so they ship them, and they’re made out of plastic, which uses fossil fuels in its production. All those things are harmful to the environment.”

More than 80% of Christmas trees are manufactured in China, where factories rely on coal, one of the dirtiest fossil fuels for the numerous pollutants it emits when burned, to generate electricity. Diesel fuel-powered ships then transport these trees across the ocean, further contributing to carbon dioxide emissions and global warming.

On average, one artificial Christmas tree contributes to 88 pounds of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere, the equivalent of driving a gas car 115 miles. In contrast, a single Douglas fir tree, the most common species of Christmas tree and the best carbon-capturing tree, absorbs 17 pounds of carbon dioxide each year.

As the 2023 holiday season concludes and families remove the festive twinkling lights from the roof and the delicate ornaments from the tree, now is a better time than ever to consider future environmental footprints.

Instead of throwing away the artificial tree, pack it back up into its box to reuse for years to come. This will significantly reduce the amount of waste and toxins that end up in dumpsters or even natural ecosystems.

Furthermore, for those who bought a live tree this year, consider ways to repurpose its every part. From decorative wreaths, to enticing birdfeeders and seasonal spiced cooking, the possibilities for recycling the firs’ needles, branches, and trunk are truly endless.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)