Forbidden history impacts our lives. We should talk about it.

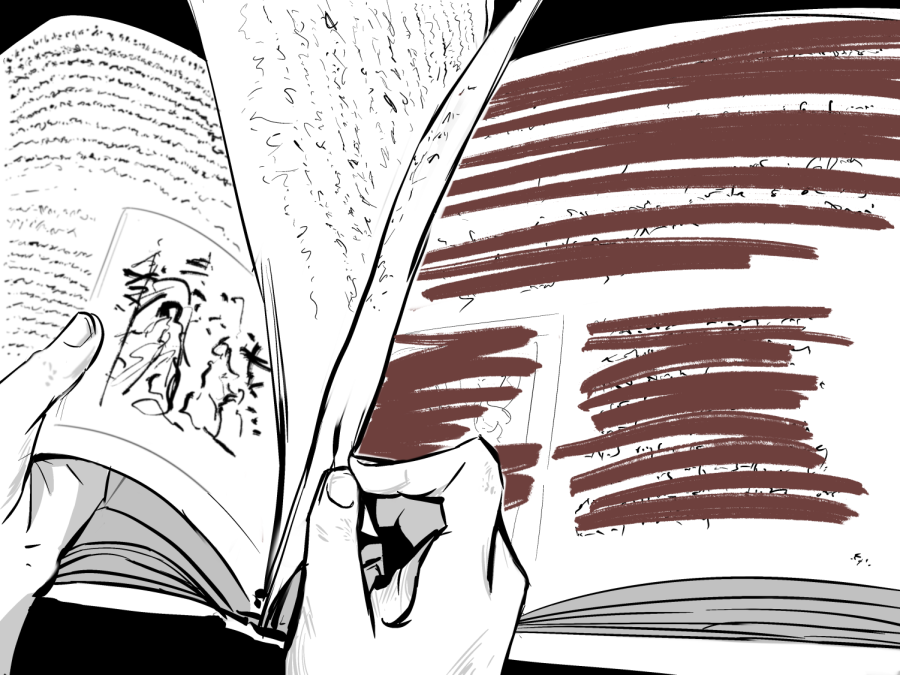

An illustration of history textbooks. When we deliberate contrasting viewpoints as well as the hard facts of the situation, we develop better understandings of each other and a more complete view of the world.

Trigger warning: This article includes discussion about human deaths, racial injustice, the Tuskegee syphilis experiment and the Tulsa race massacre. We advise readers who may be sensitive about these topics to reconsider reading this piece.

In school, teachers often tell us that learning history is a way to avoid making the same mistakes again, that by analyzing and understanding those mistakes, we will be better equipped to approach the same situations in the future. But as I have learned more about history beyond the lens of the classroom, I believe more and more that we have an imperfect view of our own history due our inability to discuss these topics.

The narrative around American history especially in elementary school often depicts the United States of America as the best nation. However, while America has numerous commendable accomplishments, this oversimplification of our history has deep and resounding consequences of a generation without a complete picture of the past. Many of the bleaker parts of our history such as the 1932 Tuskegee syphilis experiment or the 1921 Tulsa race massacre, which mistreated minorities, are widely unknown and untaught in schools across America.

The Tuskegee syphilis experiment, a government-funded study lasting from 1932 to 1972, took advantage of the lack of medical understanding of Black men to intentionally leave them untreated for syphilis in order to study the full progression of the disease, even when a cure became widely recommended. Scientists told hundreds of men, mostly uneducated sharecroppers, that they were being provided with medical treatment for “bad blood.” In reality, they were only given placebos.

Before the study was shut down, 128 men had died from syphilis-related causes and the disease had further spread among the community. Even though this study caused a deep-rooted mistrust of government institutions in the Black community and discouraged many of them from seeking medical care, according to a study conducted by Stanford University, the topic is still fairly unknown due to its racial undertones.

The overall sensitivity of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment due to the breach in human ethics, often leads us as a society to be unwilling to discuss it. Our own reluctance only exacerbates this issue by creating a stigma around sensitive racial topics, labeling them as taboo or forbidden. Glossing over events with such deep repercussions will only create a society where discussing and debating these topics is discouraged.

In the Tulsa race massacre of 1921, after a white woman accused Dick Rowland, a Black teenager, of assaulting her, racial tensions culminated in a massive riot where thousands of white men stormed the predominantly Black Greenwood neighborhood. The mob burned down thousands of homes and churches, leaving many homeless and shattering the prospering Black community.

An official count in 2001 cited the death toll as 36, but as many as 300 could have died that day. Later on, police reports and archives about the massacre went missing as officials attempted to cover up the riot. In 2012, a bill, which would have mandated the riot to be taught in all Oklahoman schools, failed to pass in the state legislature, and lawmakers claimed that schools were already teaching the riot. However, a study conducted by the Oklahoman discovered that 83% of people surveyed had never heard of the Tulsa race massacre. Furthermore, few had learned of the event inside school classrooms.

Our own attempts to hide the massacre illustrate a key point in today’s world, where the shame from these topics makes us hesitate to discuss them. People tend to shy away from talking about their own mistakes because we want others to remember us not for our missteps but our achievements. Similarly in history, society overall has shied away from talking about these mistakes; however, in the present day, we need to feel comfortable owning up to our own mistakes, understanding them and preventing them from happening again. History is immutable; despite our efforts in the present, it will never change. The best thing we can do is understand it to the fullest.

In today’s world, this hiding of history is still prevalent as the recent surge of book banning demonstrates our efforts to shape the narrative around current history. These book bans allow politicians and groups around the country to change teaching curriculums, shifting them away from topics that they want to avoid. With a large portion of these books pertaining to LGBTQ+ or racial themes, this lack of literature, representing those topics, will only contribute to the feeling of discrimination against minorities.

At Harker, we have placed an emphasis on learning about these more unknown parts of history, covering the Tuskegee syphilis experiment in biology classes and discussing the Tulsa race massacre in AP United States History. In addition, we have increased the diversity of books in English curriculums, leading to a broader array of perspectives being taught. However, we need to continue with this movement by creating classroom environments where the discussion of polarizing topics is considered the norm.

As a polarizing topic, sensitive history will, without a doubt, create many conflicting opinions. However, that is yet another reason it should be discussed. When we deliberate contrasting viewpoints as well as the hard facts of the situation, we develop better understandings of each other and a more complete view of the world.

The Tuskegee syphilis experiment and the Tulsa race massacre have long been hidden parts of history, omitted from textbooks and erased from reports. We need to become more aware and comfortable with these parts of our history in order to become a society which respects each other. Especially as our freedoms and the restrictions upon them become more prevalent issues, it is even more important to acknowledge and understand our history.

Isabella Lo (12) is a Managing editor for Harker Aquila, and this is her fourth year on staff. This year, she looks forward to learning more about multimedia...

Mirabelle Feng (12) is a Student Life editor for the TALON Yearbook, and this is her fourth year on staff. This year, she looks forward to creating unique...

![LALC Vice President of External Affairs Raeanne Li (11) explains the International Phonetic Alphabet to attendees. "We decided to have more fun topics this year instead of just talking about the same things every year so our older members can also [enjoy],” Raeanne said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_4627-1200x795.jpg)

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)