So you wanna be a Guggenheim award-winning artist?

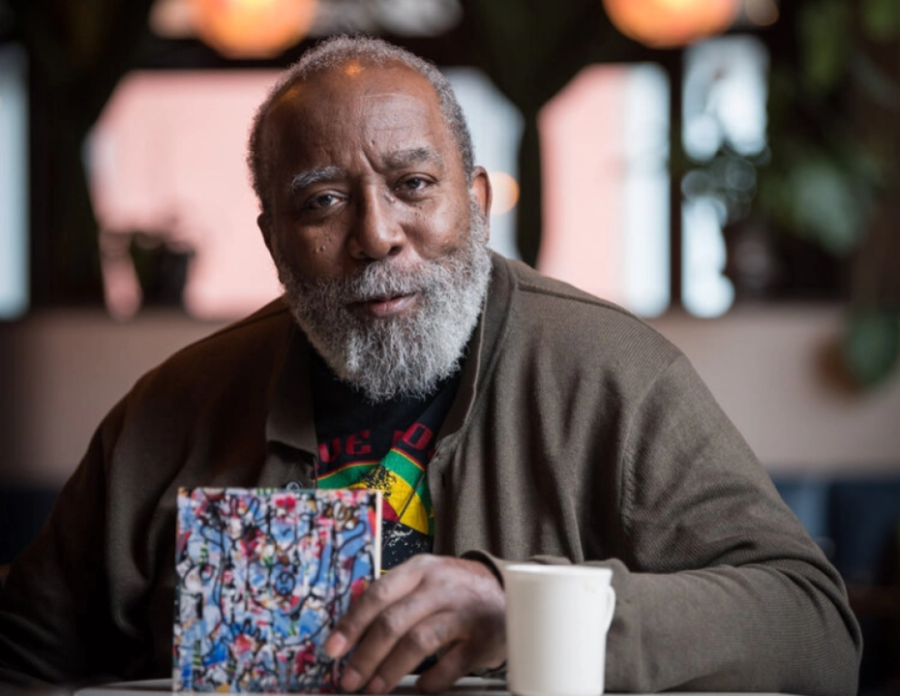

Visual artist Ta-coumba Aiken works with color and motion, winning a Guggenheim Fellowship Award this year

When Ta-coumba Aiken got the phone call announcing his Guggenheim Fellowship Award, he didn’t believe it at first. Aiken had applied for the award eight times previously, but in April 2022 he received the prestigious prize, in the Fine Arts category.

The Guggenheim Memorial Foundation recognizes artists and scientists throughout the nation, and 180 fellowships were awarded in April of this year. The foundation selected Aiken out of 2500 other applicants in the Fine Arts category, recognizing him for his work in dynamic art, specifically spirit writing and rhythm patterns.

Aiken described finding beats in art, similar to the beats in music and jazz, building together to form a rhythmic pattern. Aiken found these styles in indigenous culture, with spirits of different types of music, and used these abstract dances of beats and flows to create art. His work often involves bright colors and dancing lines, filling space and color.

“I just started trying to figure out why certain things were popular and why other things weren’t,” Aiken said. “So I based on music, and cultural music from different places, and then noticed that there was this constant regular beat, and that became the rhythm pattern. That was the spirit of it.”

Aiken started creating art at three years old, in his Illinois home in the 1950s, and he presented his first art exhibit in the house’s basement at age six. Pricing his art and inviting neighbors to come, Aiken started attracting other buyers, and he ended up gathering $657.36 from that first exposition.

Aiken’s passion for visual art continued, and he attended the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, residing in that city for many years since. Aiken started doing illustrations such as for set designs and posters for shows, to make a living, before making a name for himself and starting public art in Minneapolis. Years later, after receiving the Guggenheim award, he still is grateful for just being alive and the success of his art.

“People say, ‘Oh, you deserve this, blah, blah, blah,’” Aiken said. “I’m like, I work every day, I paint and draw and do whatever I can do for our community every single day. So what I deserve is to be able to breathe and be thankful for breathing, and anything after that is icing on the cake. But I was exceedingly grateful to be recognized.”

One such example of Aiken’s public art was his Guinness World Record-winning Lite-Brite mural, in which he assembled 596,000 Lite-Brite pegs that light up in bright colors. The mural won the record for Largest Lite Brite Picture, and was designed by Aiken with funding from the Forever Saint Paul Challenge and St. Paul Foundation, as well as help from the public.

“I had something like 600 volunteers, some were homeless, and some were district court judges and senators, and I got all these different people from all different walks of life working on it,” Aiken said. “So I guess I’ve been just mimicking my life through my art all this time.”

Other examples of Aiken’s public art include a mural etched in glass in St. Paul and various sculptures in cast bronze at the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden or a 76-foot wide mural painted on cover coated steel, decorating Minnesota for any visitors to see.

“I did public art because people couldn’t afford my paintings, and I thought, ‘How is there a way that I can do my art, and millions can see it for free, but one person pays for it?’” Aiken said. “It was mainly because I believe in people, and I want people to see things, and I don’t think that one certain class of people should have everything, and then other people get the crumbs of that. Even though we leave the crumbs for other people, they create new fashion, new music, new design, new stuff.”

Aiken’s current studio is decorated with various finished and unfinished pieces of artwork of different colors and sizes, as he continues his journey through art. He reminds aspiring artists of the possibilities in new art and curiosity.

“Don’t just wait for what’s happening in there, but go to the museums and look at the painting and ask how it was done,” Aiken said. “How’d it get up there, literally have the conversation with the piece, then go and study that.”

Sally Zhu (12) is the co-editor-in-chief of Harker Aquila, and this is her fourth year on staff. This year, Sally wishes to interview more people around...

Sarah Mohammed (12) is the co-editor-in-chief of the Winged Post, and this is her fourth year on staff. This year, she is excited to help make beautiful...

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)