The Poet’s Project: How poetry teaches us to be tender together

Poet Rachel Mennies turns to language for vulnerability

Provided by Rachel Mennies

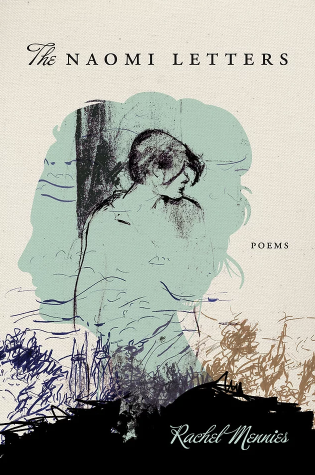

Rachel Mennies is a poet and the author of “The Naomi Letters (BOA Editions, 2021) and “The Glad Hand of God Points Backwards” (Texas Tech University Press), finds poetry to be a site of tenderness. Her most recent collection explores this tenderness through the epistolary form, as she writes lush letters to an imaginary woman.

April 30, 2022

Rachel Mennies is a poet and the author of “The Naomi Letters” (BOA Editions, 2021) and “The Glad Hand of God Points Backwards” (Texas Tech University Press), which was named a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award. Her poetry and essays appear in the “Poetry Foundation,” “Lithub,” “The Believer,” “Kenyon Review” and “American Poetry Review.”

Mennies has taught writing at Carnegie Mellon University, Chatham University, Penn State University and Loyola University Chicago and was the 2021-2022 Walton Visiting Writer in Poetry for the University of Arkansas MFA Program in Creative Writing and Translation. She currently serves as reviews editor for “AGNI,” a literary magazine based in Boston University.

Mennies spoke with Winged Post and Aquila Features Editor Sarah Mohammed (11) about the epistolary form in her new book, to write about vulnerability and share it with the world and how she has navigated the process of releasing and promoting a new book during the pandemic.

I do the worst work at the beginning of my writing process if my head is at the end of the process. If I’m trying to ask myself when I’m sitting down with a blank page or a new project “how can I achieve this end writing goal,” I do the worst work. I don’t know that there’s really a foolproof way to say, “I’m going to write these kinds of poems” or “I’m going to write this kind of subject matter and I’m guaranteed [a certain result].”

For “The Naomi Letters,” what really helped me address the question of “Who am I writing for?” is that when I started this project, I wasn’t deliberately starting a book — I was writing, though.

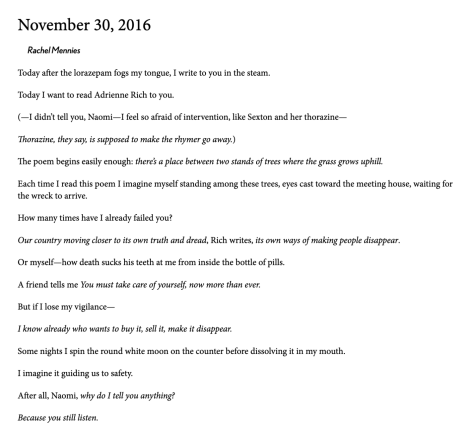

Going through difficult periods of mental illness and some great internal difficulties, I was like, “I need to talk to somebody about some of this stuff and I need to write it down.” I don’t really have language for what I’ve just been through — I’m barely on the other side, or maybe even not on the other side — so I’m going to just write letters to an imaginary person. I’m not going to call them poems. I’m going to be vulnerable, I’m going to write a lot down, I’m going to write a couple times a week in the early morning, I’m just going to have this conversation with this imaginary woman.

I ended up stumbling into the epistolary form [of poems formatted like letters, addressed to a person] because I was writing work that was so heavily rooted in disclosure and admission, so I was like, “I have to tell you something. I want to tell you a secret.” I love the epistolary form because it holds to me the paradoxical tension between public and private — you’re reading something that’s representing itself in the letter, but in a more public space. They’re meant to be public, but the conceit of them is that they are a private communication or semi-private communication between the two people.

I turned to monostiches [where each line in the poem is its own stanza] because I wanted [the work in “The Naomi Letters”] to feel like letters but feel like poems at the same time — and I love the drama of the monostich. There are poets whose work I really really admire who walk that line really powerfully — I’m thinking of poets like Simeon Berry, who does really cool work with straddling this line between lineated and prose poetry. I’m really fascinated by that.

I started the book in the summer of 2016, at this point very much a private writing process. A year later, when I had 100 pages of work, I turned to the people in my small circle that I trusted and that’s where it got a little bit bigger. From there, it became a manuscript, whose publisher I found in 2019.

The greatest thing that I can imagine that will happen to the book is that I get to have a conversation with somebody about it, because we’re all in these private Zoom boxes now. Finding other people who have connected with the vulnerability and the tenderness of the book that I hope it captures is the thing that means more to me than anything else I probably could have imagined in the world in which I was writing a book.

I spent my entire 20s on Tumblr. If you had told me that this book would find traction on Tumblr back then I would have just died of happiness a thousand times. I’ve seen it bubble up on there — it’s made me imagine my younger self, and I’m still very touched to know that people are “retumblring” it. Just seeing it pop up on different blocks on that website just makes me so happy.

I believe in the power of vulnerability in writing and in earnestness and tenderness as deep seats of artistic power, interpersonal power. The lines that bubble up on Tumblr are the ones that are like, “How do I look away now that I’ve seen you.” I’m really touched that some of the more vulnerable moments in the book are the ones that kind of pop up on socials — I just feel very seen by that.

It’s funny how those things happen after you finish. You can’t really say as a writer who’s going to cherish or what’s going to land with a reader, so it’s cool to see what folks have found and felt in their own readings. When I read books now, I underline things that I love and I bring them into spaces with friends and I see what they have underlined.

There is something about the way that forcing us to virtual spaces hopefully also made a lot of poetry communities more accessible to one another, whether it’s a question of being able to attend or participate in readings that you were previously geographically bound to. I can say from personal experience that doing a virtual book launch is wildly more affordable and accessible [than an in-person one].

I do think that [these virtual literary events coming out of the pandemic] hopefully could be the beginning of some more radical reimagining of how we gather and celebrate one another’s work, publish one another’s work and commune in ways that are less bound by individual poets’ income or institutional access and physical ability. I’m curious when that happens, what lessons we’ll take from that and bring back into the reopen for a safer world.

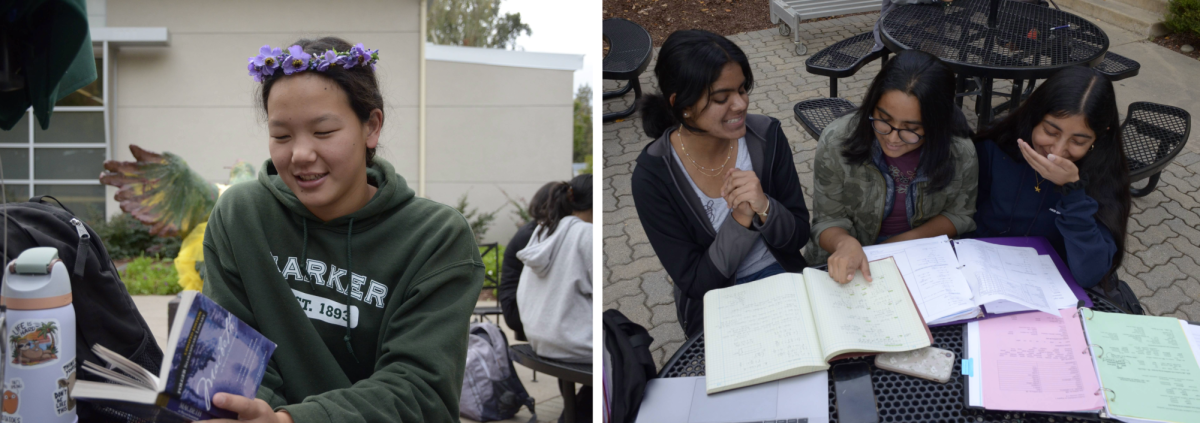

![LALC Vice President of External Affairs Raeanne Li (11) explains the International Phonetic Alphabet to attendees. "We decided to have more fun topics this year instead of just talking about the same things every year so our older members can also [enjoy],” Raeanne said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_4627-1200x795.jpg)

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)