The Poet’s Project: “Taking the world apart at its smallest level”

Poet Ruben Quesada cultivates poetic spaces of joy, diversity and inclusion

Provided by Ruben Quesada

“My role as a poet, as a person in the literary community is to advocate for literature, my own and others’. I think that’s an incredible responsibility, and one that I take on and welcome,” poet Ruben Quesada said.

August 21, 2021

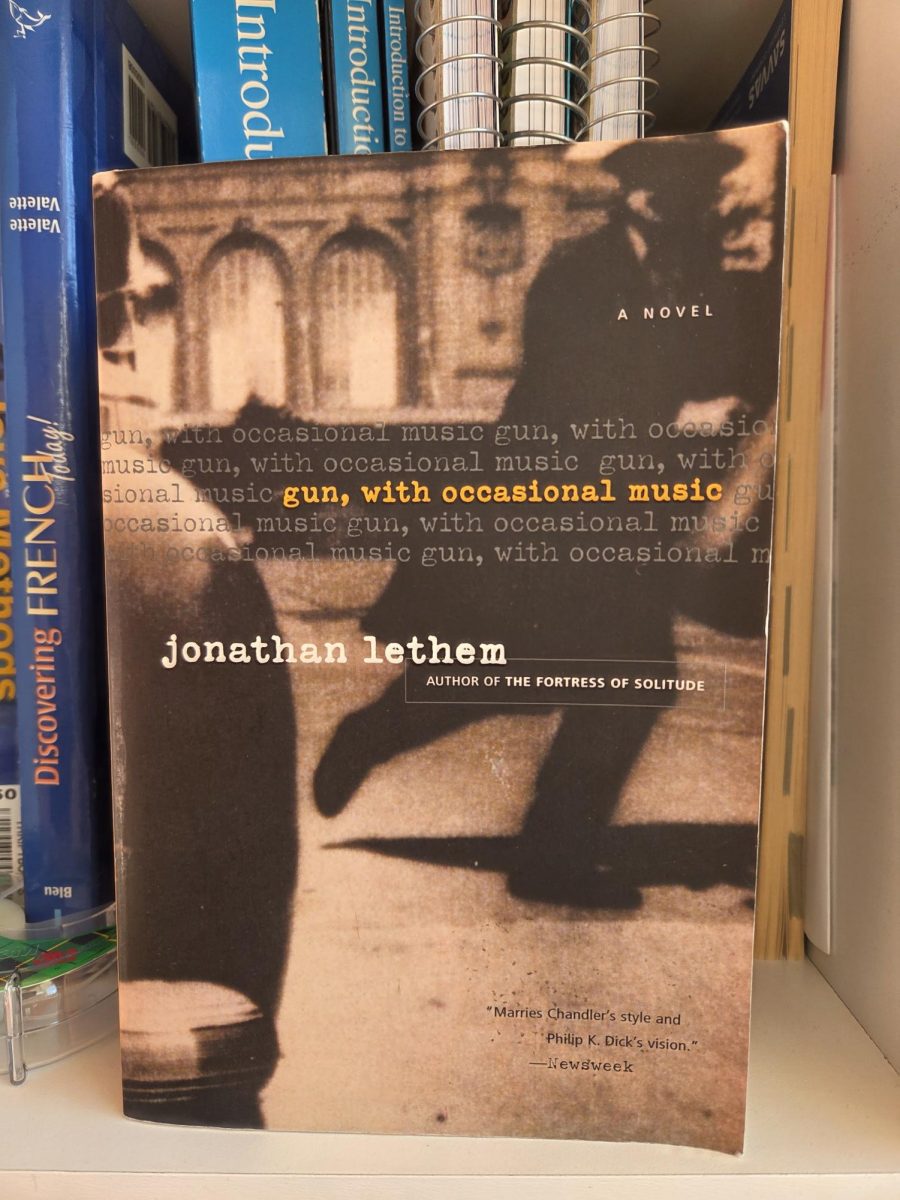

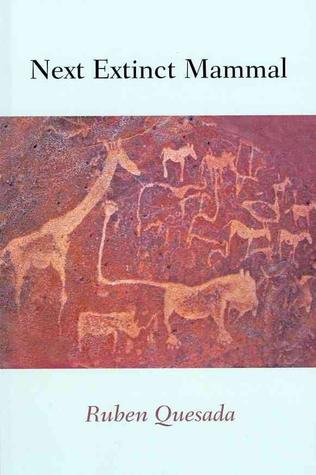

Ruben Quesada is a Latinx poet, critic and community organizer raised in Los Angeles and currently living in Chicago. He is the author of two poetry collections, “Revelations” (Sibling Rivalry Press 2018) and “Next Extinct Mammal” (Greenhouse Review Press 2011), and a chapbook of translation, “Exiled from the Throne of Night: Selected Translations of Luis Cernuda” (Aureole Press 2008). Quesada works with the National Book Critics Circle as a Board Member and the Vice President of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion.

He holds a Ph.D. in Literature and M.F.A.s in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts. His writing appears in Best American Poetry, Harvard Review, American Poetry Review and elsewhere.

Quesada has taught at the University of California, Northwestern University, Vermont College of Fine Arts, The School of the Art Institute, the Attic Institute and the Writer’s Program at the University of California, Los Angeles. He has received fellowships from CantoMundo, Lambda Literary Writers’ Retreat, Santa Fe Art Institute, among others. Quesada blogs about poetic practices and insights for The Kenyon Review.

Quesada spoke with Aquila and Winged Post Features Editor Sarah Mohammed (11) about his experiences growing up and beginning to write, his focus on creating spaces for Latinx poets and writers and the role of social media in promoting and sharing contemporary poetry.

Early on, I remember being very interested in science. I remember being about eight or nine, going to the public library and trying to get as much information about space and relativity. I tried to find books on Einstein’s theories. There was something that just fascinated me about space and about the world around us and about trying to understand the different elements and components that create everything around us.

And when I try to think of an analogy to that idea, I think about people who engage in the practice of ceramics, people who can create something out of nothing. I’m just so fascinated by that idea: it’s almost godlike, the way they can create these things. I’ve come to learn that language can function in a similar way: it can create universes, it can create worlds in our imaginations.

But, growing up, I wanted to know what was behind the physical world around me, so I really gravitated towards science and math. I remember loving my chemistry class in high school and loving my physics class and thinking, “This is what I want to do, I want to figure out and take the world apart at its smallest level.”

When I was about 13, I started keeping what many might call a diary. But what I did was I started writing letters to people. The letters were never meant to be sent or shared with anyone, it was just a space for me to put down my thoughts and feelings about either people or things that were happening to me, and just trying to create a space for myself to make a connection, not only to others, but to the world. I wasn’t ready to share these feelings or ideas with anyone and I thought, “Well, this would be the best way to do it, just to put it down on paper.”

Every year, I started a new journal, and I still have them. I’ve collected them. That was certainly one way to really exercise and flex the writing muscle and to get the ideas and emotions collected in a space that I could then revisit if I needed to.

I didn’t believe that I could have a life doing poetry or just writing. I’ve come to learn that a lot of working class families don’t necessarily see a career in the arts as something that is going to be useful for their children. The arts, especially in the [United States], have not traditionally been something that you get into for financial stability.

But anyhow, I had a wonderful mother. I was raised by a single parent, and my mom wanted me to follow my dreams, and she wanted me to do something that I was passionate about and something that made me happy. She’s always been a great believer in people’s joy, so I grew up with that instilled in me, and that really supported my passion for wanting to be a poet and wanting to follow the arts.

I went to college, and I studied literature. That’s what I’ve done for the last 20 years. It happens so fast; 20 years seems like a long time. When I was younger, I probably would have thought that seemed like a long time. But now, in retrospect, it went by very fast. That’s not to say that I wish I would have hurried and done more with that time, but to think that I’ve been attune to literature and to poetry for the last 20 years is a life I never imagined I would have.

Over the last 20 years, I’ve seen an exponential growth of people of color in the literary community. It’s been absolutely beautiful. At the start of the 21st century, there was a trickle of writers who were people of color or of marginalized communities. It’s been reassuring to see that the publishing community in the literary community is creating space. A lot of it, I believe, is attributed to people who created that space when they didn’t see a space.

Last summer, probably about this time last year, I was really interested in examining the frequency of Latinx people in literary journals. And I didn’t find all that many, [even with] the Latinx population in the United States [being] about 20%. Considering that, traditionally, the Latinx population doesn’t necessarily encourage their children to be artists because a lot of the Latinx population is rooted in a working class history, [and] there are people out there who have a lot of creativity within them but just don’t act on it.

I really wanted to create a space to encourage more Latinx people to put their work out into the world, and I was able to partner with [PANK] magazine. I created a portfolio last summer where I published a group of poets and writers of fiction and nonfiction, essayists and visual artists. I published them online, on the [PANK] magazine website.

I started at the beginning of July, and I ended at the end of August, and I ended up publishing just over 100 poets and writers of different varied Latinx identities and intersectionalities.

Something that I think needs to be further explored is the various intersections of Latinx identity. The next area that I’m really interested in looking at is where does the Latinx identity intersect with other races and other cultures in the world, and how do I create space for that.

There’s [also] a lot that can be done with social media—one of its greatest benefits is the ability to connect people. I think often technology has been used for various things like business capitalists needs, but as a poet and as a writer, one of the things that’s important is not only getting people to read work but connecting people to other people’s work that they may not be familiar with.

When it comes to poetry and writing, I don’t think that sharing literature to the masses and getting as many people to read a work of literature is a bad thing. I think that getting as many eyes, as many people interacting with the work of art, a work of writing, is something that is a great benefit to literature, to the people who create it and to the people who read it.

I have heard people not necessarily embracing the marketability of literature through social media, but I think it’s great for connecting communities and people to literature that may have never had access to it.

My role as a poet, as a person in the literary community is to advocate for literature, my own and others’. I think that’s an incredible responsibility, and one that I take on and welcome. With gratitude, I think that having a life where you champion the work of people that are in the world with you is one of the greatest joys and one of the greatest privileges.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)