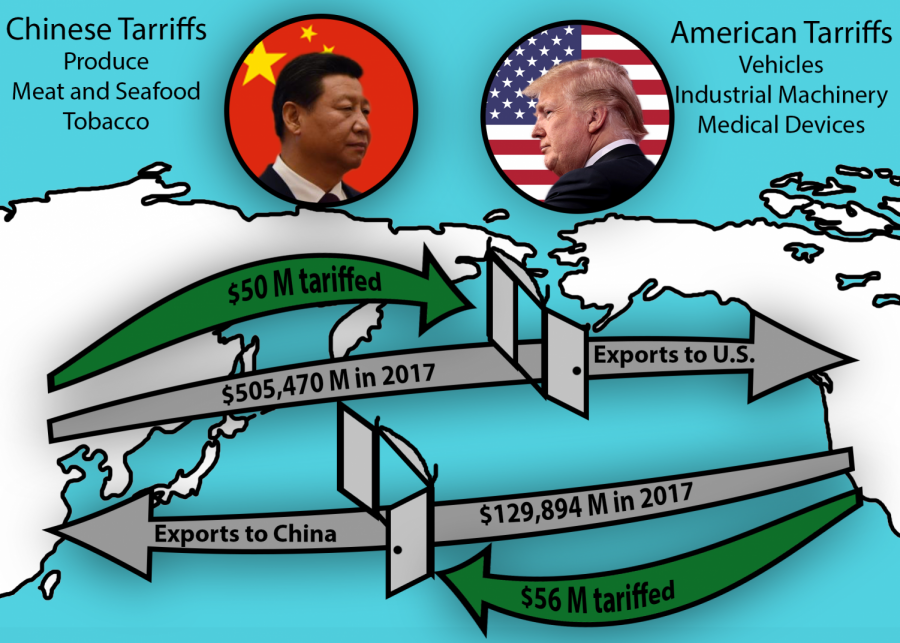

China retaliates as U.S. increases tariffs

August 31, 2018

For the past year, the United States and China have been slugging it out in one of the largest trade wars in history, in terms of the value of tariffed goods. The U.S. enacted 25 percent tariffs, that would affect $16 billion worth of Chinese goods on Aug. 23. Immediately, China responded with a 25 percent tariff of their own on an equivalent $16 billion worth of American goods.

A tariff is simply a tax that a political entity places on imports from another polity, typically to favor domestic producers and thus stimulate domestic economic growth while reducing the amount of reliance on foreign exports. However, if the country whose exports are being taxed sees the tariffs as unfair, which is nearly if not always every time, it will sign its own tariffs, which leads to another round of tariffs signed by the first country, and this cycle continues until negotiations are held.

This is the underlying basis behind every trade war: two countries trying to either alleviate or further the trade deficit with each other by applying tariffs on foreign goods and subsidizing domestic goods until one of them backs down.

“Trade wars, by definition, are pretty much always lose-lose. Because trade, by definition, with some exceptions, is generally win-win — voluntary and untouched,” upper school economics teacher Sam Lepler said. “If you want a shirt, and I want pants, and I have a shirt, and you have pants, and we trade, we are both by definition better off. So the more voluntary free trade there is, generally speaking, the more both parties are benefiting from that trade; otherwise, they wouldn’t make the deal.”

President Trump ordered the Office of the United States Trade Representative to investigate the trade relations with China on Aug 18, 2017. In a memorandum signed by President Trump in August 2017, he explains the various restrictions unfair treatment that China has imposed on the US over the years, mostly pertaining to allegedly biased intellectual property laws, intellectual property theft conducted by the Chinese government on U.S. companies. As a result, Trump enacted tariffs by March 2018 on Chinese products in an attempt to retaliate. In response, China increased taxes on American goods.

However, that time in between the first tariffs being signed and when one country backs down or tries to negotiate is usually when most consumers are hurt. For example, a $130 million construction project with about $20 million accounted for steel could have steel prices jump by $6 million when an opponent in a trade war increases tariffs. That cost could be the difference between the project being finished and it remaining incomplete.

Although the idea of trade — exchanging goods between two consenting parties — has existed for several thousand years, the modern economy relies heavily, to the point of absolute dependence in some cases, on international free trade to survive. However, this universal dependency leads to some countries taking advantage of it for personal gain. If a country, — especially one of the two largest economies in the world, China and the U.S. — decides to enact tariffs on trade or stop trade completely, most, if not all, countries contributing to the global economy would be affected.

“Nearly two-thirds of goods traded today are connected to global value chains,” World Trade Organization (WTO) Director-General Roberto Azevêdo said in a speech on May 31 to the WTO. “In this context, shocks to the trading system are likely to be globalised.”

In addition to severing economic ties between two countries, trade wars can have the consequence of also raising political and military tensions.

“When those economic interconnections dissipate, the cost of going to physical war against another place decreases — [it] becomes easier to go to war if you’re not really trading with those people,” Lepler said. “If you have a trade war that can get dramatic enough, it raises the specter of more military conflict as well.”

“[We’ll see in the longer term a hit to U.S. exporters for sure,” Lepler said. “Ultimately, [there will be] sustained higher inflation [and] higher prices in America.”

“You can look at the Smoot-Hawley tariff as maybe the most famous historical example of that, where the United States, middle of the great depression, really worried about trade and that we were buying more from abroad than they were from us,” Lepler said. “So we put a really big tariff and that killed all international trade basically. It ended up hurting both the United States and Europe dramatically.”

This piece was originally published in the pages of The Winged Post on Aug. 31, 2018.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)

![President Trump affirmed the establishment of tariffs on imported steel and aluminum on March 8 in an effort to bolster American companies that struggle to compete with foreign companies. “From an economics standpoint, the purpose of tariffs is to protect a domestic industry [and] try to boost employment in that industry under the theory or the hope of creating more steel and aluminum domestically and therefore growing the economy,” economics teacher Sam Lepler said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/IMG-1807-300x751.jpg)