Memorial held for Fields medal winner

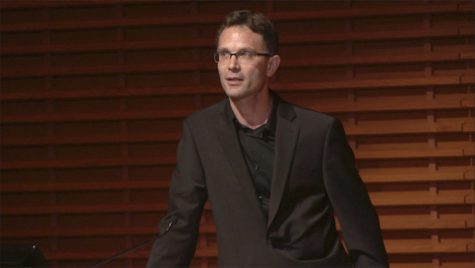

Provided by Stanford Video

A memorial service for Dr. Mirzakhani, who had taught at Stanford, was held on Oct. 21 in the CEMEX auditorium in Stanford.

November 18, 2017

Dr. Mirzakhani, renowned scholar and math genius, died on July 14 of breast cancer at age 40. Stanford University held a memorial service for Dr. Maryam Mirzakhani, professor of mathematics, on Oct. 21 at the Stanford CEMEX Auditorium.

She finished her undergraduate studies in Iran and attended Harvard University for graduate studies. In 2004, Dr. Mirzakhani was granted her PhD, and she joined the faculty at Princeton University as a Clay Mathematics Institute Research Fellow and an assistant professor. In 2008, she moved to California to become a professor of mathematics at Stanford University.

In 2014, Dr. Mirzakhani was awarded the prestigious Fields Medal, popularly considered the Nobel Prize of mathematics, for her outstanding contributions to the dynamics and geometry of Riemann surfaces and their moduli spaces. The Fields Medal was first instituted in 1936 and after 78 years, Dr. Mirzakhani became the first female mathematician to win the award.

“I thought that was very cool because she was the first woman to be honored with [the Fields Medal], and to me that’s just great reinforcement of the fact that she was determined and she was curious,” Dr. Aiyer said. “You put those two things together so you are rewarded for what you do.”

In addition, although the U.S. has been participating in the IMO since 1974, it has only sent five female contestants. At the upper school there are fewer girls in some advanced STEM classes. Dr. Aiyer observes that the percentage of girls in her advanced topics class is about 20%.

Joanna Lin (12), Math Club president, who has participated in math competitions since fourth grade, has discovered her passion for the subject.

“There is definitely an observable gender imbalance, but thankfully there are competitions like MathPrize for Girls at MIT, which allow girls around the nation to convene and meet other girls who participate in math competitions,” she said. “As a community, it’s been like a second family to me. I’ve traveled across the country and stayed hours after school for contests with this club, and it’s really a special place.”

Other students do not feel that the gender imbalance is a large hindrance to girls entering STEM.

“There are fewer girls in my advanced math topics class, but I don’t feel intimidated by that because I’m not the only girl in my class, and the guys are friendly too,” Math Club officer Grace Huang (10) said.

Dr. Mirzakhani also received the Blumenthal Award for the Advancement of Research in Pure Mathematics in 2009, and the American Mathematical Society honored her with the Satter Prize in 2013.

She inspires many young women and girls in mathematics through her numerous awards and invaluable contributions. However, Dr. Mirzakhani had not dreamt of being a mathematician in her childhood.

“As a kid I dreamt of becoming a writer,” she said in a 2008 interview with Clay Mathematics Institute, adding that her maths grades in middle school had been poor. “I never thought I would pursue mathematics before my last year in high school. I do believe that many students don’t give mathematics a real chance… I can see that without being excited mathematics can look pointless and cold. The beauty of mathematics only shows itself to more patient followers.”

Though her work is more theoretical in nature, her creative research has lot of applications in mathematics and science in areas such as theoretical physics, quantum field theory, engineering and material science, robotics, computer vision, and computer graphics. Dr. Mirzakhani’s work involved the geometric and dynamic complexities of curved surfaces such as spheres and doughnut shapes.

With the support of a more encouraging teacher and the influence of her brother, Dr. Mirzakhani, developed a passionate interest in math as a child. She demonstrated her talent for math in high school when she was a member of the Iranian team at the International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO) in 1994; she won a gold medal two years in a row and earned a perfect score in 1995.

According to Dr. Mirzakhani’s husband, Jan Vondrak, she wanted to be remembered as a role model for her drive for excellence, rather than her mathematics itself. He encouraged young people to find their own path, what they love and what is meaningful in Dr. Mirzakhani’s memory. At Harker, the students are given a multitude of course choices in order to help them discover their passions.

“We let students know its all about what you want to do and what your interests are and let them figure it out,” Dr. Aiyer said.

This piece was originally published in the pages of the Winged Post on November 16, 2017.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)