Global Reset: Tip of the iceberg

Temperatures likely to reach Paris Accord limits

September 8, 2017

This year marked a change in attitudes towards climate change – no longer is it an issue of the future. As evidenced by the urgency of the Paris climate accord, leaders and legislators have followed scientists and activists in tackling the threat of climate change. The questions that remain concern how much warming Earth can stand before certain areas become uninhabitable.

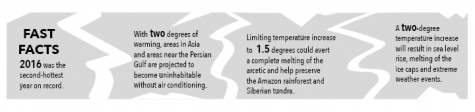

This past year has been marked by climbing temperatures, rapid consumption of fossil fuels and increasing reports of extreme weather events like droughts and floods. 2016 was the second hottest year on record. Areas such as Louisiana faced catastrophic floods, while the Californian drought raged on. These conditions are only projected to worsen if people do not work to curb carbon dioxide emissions.

“If we do nothing to fight climate change, in twenty years we’ll see a lot more of drought and floods,” said Dawn King, a lecturer at the Institute at Brown University for Environment and Society. “These changes might not happen in every geographical area—for example in California you might not experience these changes until maybe 30 to 40 years later—but low-lying island regions like Miami and New Orleans are going to be impacted.”

What is most alarming, however, is the idea that at some point in the near future, the Earth will reach a tipping point at which catastrophic events will force humans to greatly adjust their ways of living in order to survive.

This idea is based on the concept of equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS), a measurement of how global temperatures will respond to a doubling of carbon dioxide emissions in the atmosphere that offers a way of estimating how much global temperatures will change over a certain amount of time. In last September’s report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reported that the current ECS is a temperature increase of anywhere from 1.5 to 4.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels.

Determining a concrete value for ECS is difficult due to the amount of factors that affect the progression of climate change and global warming. For example, feedback mechanisms like clouds, which can both cool by blocking out sunlight and warm by absorbing heat energy from space, may either help or harm the planet.

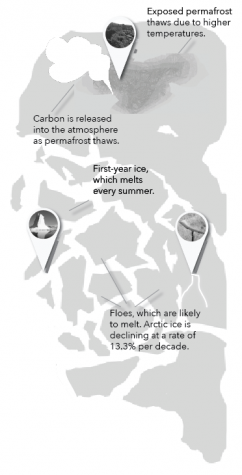

What many scientists do agree on is that regardless of the ECS value, a temperature increase of two degrees Celsius will result in sea level rise, melting of the ice caps, extreme weather events and decreased viability of agriculture, among other issues that encompass all spheres of civilization, from economy to environment. For areas near the melting ice caps or islands at low elevations, the impacts of climate change may come more rapidly as sea levels rise and ice melts.

In light of these projections, scientists and legislators alike are investigating what a temperature increase of 1.5 degrees would look like, as opposed to an increase of two degrees. Though the IPCC has not yet conducted a comprehensive study to answer this question, several studies support the idea that the 0.5 degrees will make all the difference for the planet.

According to a 2016 study by Nature, with two degrees of warming, areas of Southwest Asia and areas near the Persian Gulf are projected to become uninhabitable without air conditioning. Food crops would also be significantly less viable at two degrees as compared to 1.5 degrees.

“A changing climate will have a number of impacts on food crops. First, the area where certain crops can be grown will change … Cropping frequency may change as well, with longer frost-free periods and warmer weather on average increasing the number of crops that can be grown in certain areas, but in other cases making certain regions hostile to non-irrigated crop production,” said Christopher Seifert, a PhD student at the Stanford Center on Food Security and the Environment. “Overall, food crops in already food secure areas like Canada, Russia, and the Northern Europe may benefit from a hotter environment, while crops in places with a lot of hunger — Africa, India, Central America — are hurt.”

On the other hand, a 1.5-degree temperature increase could avert a complete melting of the Arctic, which is almost certain to occur with a two-degree increase. Currently, the melting of permafrost, a layer of frozen plants and organic matter, also poses problems as the organic material will release carbon dioxide into the air.

Limiting the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees could also preserve ecosystems such as the Amazon rain forest, the coral reefs and the Siberian tundra. It could also prevent complete inundation of low-lying land by rising sea levels.

With the signing of the Paris climate accord, country leaders also looked to an estimated temperature rise of two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels as the point of no return and acknowledged that limiting temperature rise to 1.5 degrees would be ideal. Some members of the accord have already put plans into motion to curb carbon dioxide emissions — France’s environment minister has already announced the country’s plans to ban petrol and diesel vehicles by 2040.

Though researchers see the accord as a step forward, many are skeptical about the effects that such efforts will have on global temperatures. Given that Earth’s temperatures have already risen one degree above pre-industrial levels, many agree that Earth will cross the 1.5-degree threshold by mid-century. Likewise, statistics from the IPCC indicate that carbon emissions must be kept below 430 parts per million (ppm) in order to avoid reaching 1.5 degrees of warming, and carbon emissions already reached 400 ppm in 2013.

“The 1.5 to 2 degree limit the Paris Agreement outlines won’t be enough to limit the impacts of climate change that we’re seeing today—even if we stopped all greenhouse gas activity today, there’d still be so much carbon dioxide in the air it’d take decades for it all to dissipate,” King said. “However, the Paris Agreement is a great first step towards addressing climate change as an international team.”

Additionally, President Donald Trump’s desire to withdraw from the accord poses an obstacle, as the United States contributes about 15% of global carbon dioxide emissions. Though full withdrawal from the accord will take four years, the United States’s absence from carbon-reducing efforts may hurt or inhibit the efforts of those in the accord.

With the feasibility of the accord’s goal and the setbacks faced by accord members in mind, many scientists feel that the most viable method for curbing global temperature increases is a combination of switching to forms of renewable energy and extracting carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Scientists are currently exploring ways to capture and store carbon dioxide and considering the economic viability of such efforts.

This piece was originally published in the pages of the Winged Post on September 6, 2017.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)