Comfort women: How the past still matters

The Japanese government has continued to downplay or deny claims of sexual slavery and other crimes against humanity committed during World War II. Over 70 years later, they still have failed to resolve the issue, in spite of testimonies from several victims of Japanese sexual slavery.

The Rape of Nanjing was an incident of mass slaughter and rape of innocent civilians in Nanjing, China, perpetrated by the Japanese military forces. Following the incident, the Japanese government sought to enforce discipline among soldiers. Deciding that their soldiers needed to redirect their sexual frustration in a more silent and covert way, the Japanese government abducted women or girls from their homes from various countries under imperial Japanese rule. Those who were not kidnapped were offered job opportunities in factories and restaurants.

In stark contrast to what they were promised, the women and girls were kept as sexual slaves in brutal conditions and tortured. Although women who survived were set free after World War II, they remained silent due to fear of social stigma. These survivors came to be known as comfort women.

After seeing Kim Hak Sun, a fellow former comfort woman, hold a press conference on television about her experiences, Lee Yong Soo, known by many as Grandmother Lee, first testified about her experience as a comfort woman in 1992.

Because Japan has still yet to offer satisfactory legal reparations, Grandmother Lee continues to testify about her harrowing experiences as a comfort woman.

In 2007, she recounted her treatment at the hands of the Japanese military to the United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs, and ended her testimony by directly addressing the Japanese government.

“If you cannot apologize, then give me back my youth,” she said.

Grandmother Lee spoke at an event at the Santa Clara University campus with Esther Peralez-Dieckmann, the director of the Office of Women’s Policy of Santa Clara County, on March. 11.

The event was hosted by Congressman Mike Honda, a longtime advocate in the United States for women’s and humans’ rights. He is also one of the few active voices in the United States government in the fight for proper reparations for comfort women from the Japanese government.

Grandmother Lee (left) answers a question from the audience. The event was hosted at Santa Clara University on March 11.

Director Peralez-Dieckmann, a staunch supporter in the effort to stop human slavery in the Bay Area, gave the opening statement, which compared the comfort women with victims of human trafficking today.

“Even when a victim is rescued, it can take years,” Director Peralez-Dieckmann said. “Two, three, four, five, even longer to resolve the issue, to make sure they get important services, to make sure that they can restore their lives and deal with all the aftermath of the violence.”

The Santa Clara County has trained individuals to provide immediate aid to victims of human trafficking by using online videos or providing them with reports on the situation in certain areas.

“One of the things we’re really excited about, and you can find it on Youtube, we created a 12 minute know the red flags training video,” Peralez-Dieckmann said. “That training has gone across the Bay Area, and it’s 12 minutes of what is human trafficking, what are the myths around human trafficking, because you hear about it, and you think it’s mostly international, but 70 percent of the victims of human trafficking identified in the Bay Area are actually from this area.”

According to a report compiled by the City and County of San Francisco’s Department on the Status of Women, over 250 known and suspected human trafficking survivors have been identified by 19 government and community-based agencies.

Following Director Peralez-Dieckmann’s speech, Congressman Honda delved into the origins of the comfort women.

“Those who were kidnapped, coerced, and taken away to be used as sex slaves – sometimes mutilated and killed – had their youth and dignity taken away from them,” Congressman Honda said. “I know, as a schoolteacher, I learned that Japan’s Ministry of Education sought to omit or downplay the comfort women tragedy in its approved textbooks. Japan is a democratic emerging nation, and it wants to take leadership in the world, and they want to make sure that their slate’s clean in this era.”

The story of the comfort women has touched many, including students at the Harker School. Ayla Ekici (12), a member of the FEM Club, agreed with Congressman Honda.

“I think that globally, we need to look back on our history, and learn from it, and not just forget and deny things that were especially hard and difficult,” Ayla said. “Sexual violence is definitely a worldwide issue, regardless of when it happened, and it should be regarded as such.”

According to Congressman Honda, the issue became apparent to him in 1992, at a Stanford pictorial display titled “The Atrocities of the Japanese Military in Asia,” which consisted of images from the Sino-Japanese war, the Rape of Nanjing, and of comfort women.

“I started doing some research and getting a little more involved in it, and 1997, I started to get more active at the state assembly and began promoting a resolution, assembly joint resolution 27, which meant a lot of resistance from our own community, Japanese Americans, and some my colleagues who were Japanese American too, but we got it voted unanimously in 1999,” Congressman Honda said.

The assembly joint resolution called for the Japanese government to offer a specific apology for the Japanese military’s crimes against humanity during World War II, and for the President of the United States to urge the Japanese government to issue said apology.

Japan paid a paltry compensation fee of ¥1 billion, or $8.3 million to the South Korean government on Dec. 28, 2015, with the majority of the Korean population and former comfort women seeing the “resolution” as insincere and unsatisfying. Many of the former comfort women desired a formal public apology from Shinzo Abe, Japan’s current prime minister and the correction of Japan’s history textbooks, rather than money.

“The grandmothers, the former comfort women, have stood in front of the Japanese Embassy for 25 years for justice,” Grandmother Lee said. “How can both governments, Korean and Japanese, just simply disregard us when we ourselves have experienced the horrors of being comfort women?”

“How can this be seen as a resolution when our opinions have been overlooked? What I want, no, what we want, is for the Japanese prime minister to kneel down in front of us, and touch his forehead to the ground in sincere apology.”

Prime Minister Abe is known for his views on the history of Japan. He stated in 2007 that there was no evidence that the Japanese government kept sex slaves, despite the fact that Chief Cabinet Secretary Yohei Kono already admitted to the use of coercion in 1993, and a UN Human Rights report on the subject. Abe continues to deny and evade claims of Japan’s usage of sexual slavery and comfort women.

The prime minister also formerly led the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform, a society that promotes a nationalistic version of Japanese history. A textbook written by the Society were heavily criticized by many Western historians for the downplaying or not including full accounts of Imperial Japanese war crimes during World War II, including the abduction and torture of comfort women.

Estimates of the number of women forced to pleasure Japanese soldiers have varied. According to George Hicks, an American war journalist, who based the estimation off of a presumed ratio of women to overall troop numbers, there were 139,000 victims of forced prostitution.

A memo from the Operations Journal from Setsuzo Kinbara, Chief of the Medical Affairs Section in the Medical Affairs Department of the War Ministry, reads: “Brought in a group of comfort women – 1 woman for 100 soldiers.”

There remain only approximately 50 known comfort women survivors in South Korea, a number that continues to slowly decrease.

Grandmother Lee, one of the 50, was kidnapped from her home by a Japanese soldier at the age of 15, and was shipped via train along with five other girls to Pyongyang.

“I was riding on a train for the first time in my life, at 15 years old. I realized that wherever I was going, it wasn’t good, and I started to plead, ‘I don’t want to go, I want to go home,’” Grandmother Lee said. “The Japanese soldier began to snarl, ‘Josun jin, Josun jin,’ and started to kick me with his boots. He started to pound away at my head with his fists, and then he pressed my face to to the ground with his boot. I was confused. What did I do wrong? Why was I, a proud daughter of the Josun dynasty, being treated as though I was lower than trash?”

The soldier called Grandmother Lee “Josun jin,” or the derogatory term for “Korean” in Japanese. It was a bitter reminder to the colonized Koreans that the Korean peninsula’s last dynasty was no more, and that a new tyrannical power had taken its place.

After arriving in Pyongyang, the girls were immediately sent to Anju, another city located in the northern region of the Korean peninsula.

“There were navy ships at the port, and they shipped us onto the one at the end of the dock,” Grandmother Lee recalled. “There were around 300 soldiers who were also boarding the ship. I went to the bathroom. As I was about to go outside the stall, I saw a pair of army boots through the stall. They tried to restrain me, but I bit their arms. These men, these demons, outnumbered us by 300 to 6. And then they started to rape us.”

The boat’s destination was a comfort station in the mountains of Hsinchu County, Taiwan, where Grandmother Lee would suffer horrific treatment at the hands of Japanese soldiers for the rest of World War II.

After being subjected to rape, electric torture and beatings, Grandmother Lee was finally able to return home after the Battle of Okinawa, only to find her parents holding a memorial service for her. They did not recognize her. Although she had come home, Grandmother Lee feared great social stigma for being unable to give birth.

“My body no longer functioned as it did before. I could not give birth, neither could I marry,” Grandmother Lee said, blinking back tears. “I thought I was worthless. I thought I was one of the only ones taken away from their homes, but I was wrong.”

After testifying about her experiences as a comfort woman in 1992, Grandmother Lee joined the movement to receive legal reparations from the Japanese government. She now constantly participates in weekly demonstrations, along with fellow former comfort women, in front of the Japanese embassy in South Korea.

“Whether there was rain or snow, for 25 years, I and other former comfort women have stood in front of the Japanese Embassy, demanding moral apologies and legal reparations,” Grandmother Lee said. “As we stood in front of the Japanese embassy, people all over the world came to stand with us.”

Grandmother Lee now continues to fight for an apology from Japan not only for herself and other comfort women, but for all victims of sexual violence.

“It is difficult for me to tell people exactly what happened; when I do, I must hold back my tears every time,” Grandmother Lee said. “For the women in this world, it is necessary that these sort of crimes are rooted out. It is necessary that I testify.”

After hearing about Grandmother Lee’s story, Ayla expressed similar sentiments.

“This doesn’t get much coverage in the Western world,” Ayla said. “We definitely need to do something about it, and help these women who were used as sexual tools.”

The first rally for reparations for comfort women was held in front of the Japanese Embassy located in Seoul, 1992. The rallies continue to be held every Wednesday to this day.

“Every Wednesday, for 25 years, I protest in front of the Japanese Embassy. But now, it’s not just for myself. It’s for all the women in the world who have suffered, or might suffer, sexual violence. I used to be a victim, but now, as a women’s rights and human rights activist, I will fight back. As long as the roots remain, these sort of problems will always grow back. I firmly believe that Japan’s apology will be the first step towards cutting through the deep roots of history.”

Despite her patience, Grandmother Lee has become increasingly frustrated with the waning interest on the issue of comfort women.

“There is evidence and testimony against Japan! I myself am a live witness, evidence, of their crimes,” Grandma Lee exclaimed. “And yet, they still deny it. They have been lying from the very beginning, and they are continuing to do so. They are determined to lie to the bitter end. We cannot stay beaten, and continue to be beaten.”

“I have remained alive for all these years for the sole purpose of revealing the truth. The day I die is the day the truth is revealed and recognized.”

This piece was originally published in the pages of The Winged Post on May 4, 2016.

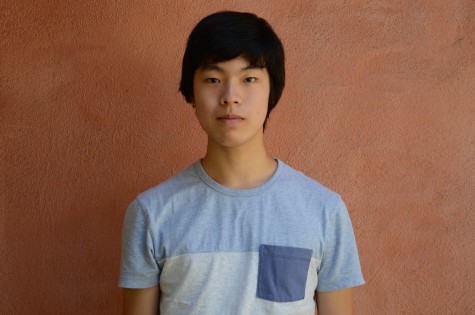

Brian Park (9) is a reporter for the Winged Post. As a newcomer journalist, he is looking forward to being able to write on various topics the campus has...

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)