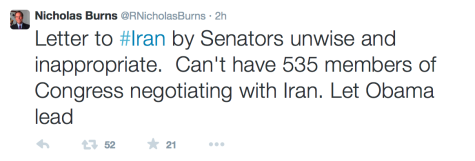

U.S. and Iran approach nuclear deal for a reduction of sanctions

The White House

President Obama meets with Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu in October 2014 to discuss Iran’s nuclear program.

As the March 24 deadline inches closer, the coalition of Western states and Iran continue to negotiate a deal that would constrain Tehran’s nuclear program.

The P5+1 (U.N. Security Council permanent members — Britain, China, France, Russia, and the U.S. — and Germany) wants limits on Iran’s centrifuges, the elimination of most of its existing fuel and the permission to conduct routine inspections — in return for an attenuation of economic sanctions. According to a news article published in the New York Times on Feb. 23, Iranian production of nuclear fuel will ostensibly be limited for 10 years under a deal. Tehran would like to see such sanctions lifted, affirming that it is not seeking nuclear energy for military purposes.

“They must either reach an agreement with Iran within the framework of logic and international law and the sooner they do it, it’ll benefit everyone involved,” President Hassan Rouhani of Iran said at a cabinet meeting on March 4, according to a government transcript. “Or else they will have to deny the facts and continue with their sanctions regime, in which scenario they will have to witness the faster progress of Iran’s peaceful nuclear program.”

Dr. Matthew Bunn shared his insights on the deal in a phone interview with the Winged Post. Bunn served for three years as an adviser to the Office of Science and Technology Policy, where he played a major role in U. S. policies related to the disposition of nuclear weapons materials in the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. For President Clinton, he directed a clandestine report on security for nuclear materials in Russia.

He is referring to Israeli PM Binyamin Netanyahu’s blowhard campaign for the West to drop negotiations entirely. Israel instead seeks an indefinite moratorium on Tehran’s construction of nuclear infrastructure, predicting that Iran would capitulate if sanctions were tightened.

Dr. Bunn further explained why Israel’s proposition would fail, noting that if a deal was clinched, the Iranian government would not surrender loosened sanctions solely for a nuclear bomb.

“Politically, [successful negotiations] would create a flow of benefits to Iran, including to powerful players within Iran [who] would not want to cut off [such benefits], and would reduce the sense of threat in Iran, particularly since it would be an agreement with all of the permanent members of the U. N. Security Council,” he said. “I think as a result of Netanyahu’s visit, Obama probably has a slightly better chance than he had before of being able to sustain a veto [of any further sanctions that would scupper the deal].”

Even CNN’s Fareed Zakaria, not often a vehement critic of U.S. government policy, declared that Netanyahu had “entered never-never land” after the prime minister spoke on March 3 before a joint session of Congress — a rare, provocative gesture by any foreign leader. Netanyahu ventured to galvanize House Republicans against President Obama’s plan, which is largely backed by Western Europe.

Robert Einhorn, a senior fellow with the Arms Control and Non-Proliferation Initiative at the Brookings Institution, wrote an op-ed in the New York Times on Feb. 26 advocating for a diplomatic settlement between Iran and the U.S. During the Clinton administration, Einhorn was the Assistant Secretary for Non-Proliferation at the State Department, and during the Obama administration he was the Secretary of State’s Special Advisor for Nonproliferation and Arms Control.

Einhorn shared his insights in a phone interview with the Winged Post.

“It’s not a perfect agreement, and it will be a controversial agreement, but I think it is far better than the alternatives to a negotiated solution,” he said. “[Netanyahu] is asking us to achieve the unachievable. In principle, it would be better to get everything Netanyahu wants, but I would say it’s impossible.”

On March 5, Secretary of State John Kerry stopped in Riyadh to reassure Saudi officials that their interests will be protected in the face of a deal with largely Shia Iran. Sunni leaders worry that loosened economic sanctions will enable Iran to supply aid and possibly paramilitary forces to Alawite President Bashar al-Assad of Syria in the conflict against the Islamic State, and to Hizbollah in Lebanon. Although American and Iranian goals align in Iraq and Syria, Kerry pledged that collaboration between the two countries never occurred.

“The Gulf Arab states are less focused on the specific elements of the nuclear deal than they are on what they think may be the implications of reaching any deal,” Einhorn said. “They’re concerned that if we reach a deal with Iran, there will be a shift in our allegiances in the region that will put greater importance on relying on Iran’s goodwill, distanc[ing] ourselves from our traditional allies. I don’t think that’s at all the intention of the Obama administration.”

Safia Khouja (12) is half Lebanese — she believes the prospective U.S.-Iran deal is necessary. Similarly, Felix Wu (12), a member of Harker JSA, believes that Netanyahu blundered with his largely political gesture in Washington.

According to the State Department, negotiations will resume on March 15 in Geneva after a brief interim.

This article was originally published in the pages of the Winged Post on March 13, 2015.

Shay Lari-Hosain (12) is the Editor-in-Chief and co-founder of Wingspan Magazine. Shay has interviewed 2013 Nobel Laureates, authors like Khaled Hosseini...

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)