The Poet’s Project: ‘I come to video games thinking that they’re equally capable of being art’

Keith S. Wilson finds new forms of expression in visual poetry and video games

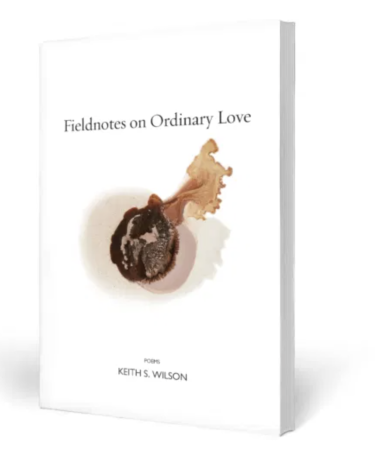

Keith S. Wilson is an Affrilachian poet, game designer and author of “Fieldnotes on Ordinary Love” (Copper Canyon), which was recognized by the New York Times as a best new book of poetry. His work has been anthologized in “Best New Poets,” “Best of the Net” and “Appalachian Reckoning: A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy,” and more of his poetry appears in Elle, Poetry, The Kenyon Review and Crab Orchard Review. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment of the Arts, Cave Canem, Kenyon Review, Stanford University and Tin House.

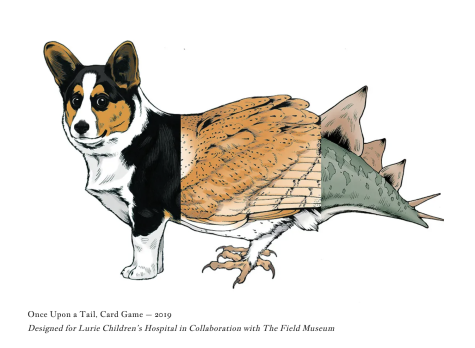

As a game designer, Wilson created “Once Upon a Tale,” a storytelling card game designed for Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago in collaboration with The Field Museum of Chicago. He has also designed alternate reality games (ARGs) for the University of Chicago. Wilson spoke with Winged Post and Aquila Features Editor Sarah Mohammed (11) about how he works in lyric forms and visual poems that explore new possibilities of existing on the page, and how these forms influence and are influenced by his making of video games.

At a young age, I loved reading — it was always like being transported to another world. My aunt read to me and my brother. She’s very performative in the way that she read it out loud: she performed poetry. She read Shakespeare and authors I don’t think I would have gotten if I read on my own, but when I saw them performed I felt like I understood them.

Visual poems [which explore new ways of existing on the page, like “line dance for an american textbook”] are really exciting to make. It feels like I’m inventing something every time I write a poem. I think all poetry is sort of like this, to a certain degree: every time you sit down and write a poem, you’re inventing a new form. Unless you’re actually making a sonnet or something that’s a received form that already exists out there, every time you write a poem, you’re making your own rules—even if you aren’t actively thinking about them. Visual poems allow me to do that to an even more exploded degree.

I’m making the form of visual poems up as I go along, and it feels really playful and experimental in a way that I really love—a way that interacts with the things that I love the most: words. Every time I sit down and make something visual it always still ends up having writing in it.

When you’re writing a visual poem, it makes you recognize the way that the words are working, the way that they fall on the page, the way that repetition works. It makes you notice those things in a new way, which is ultimately what poetry does in the first place: it gives people a new way of looking at something that they might have actually already experienced and never thought of directly. You see yourself in somebody’s poem. That’s sort of like drafting visual poems: I’m writing but I’m doing it in such a new way that it’s so exciting.

[Poet and Performer] Douglas Kearney does a lot of typographic work with fonts, and it inspires me to try to do work with fonts when I’m stuck on a poem. Turning to his poems gives me a different kind of inspiration. Poets should still read short stories and novels and plays and all kinds of different things because you never know what’s going to inspire you, or what sort of work is going to inform you, find their way on the page and help you solve problems.

Video games and visual poetry for me have a lot of intentionality. Coming to the page, any kind of reading is valid and there is some range of potential readings that I want. Same thing with a video game: there are certain kinds of things that you’re allowed to do in that game. But ultimately, you don’t really know what you’re going to walk away with, how long you’re going to spend on it; if you ask someone how long they spent on the same game, it can range radically: one person spent 10 hours and one person spent 40 hours. They have totally different answers regarding what path they took in certain video games.

There’s a way that visual poetry does that as well, where there’s a bunch of stuff on the page, but I can’t determine how you’re going to read it. Having been put in the position of the reader of a video game for so many years, I’ve done a lot of things where I was allowed to choose how to interpret or how to experience something.

Poetry has a history of interrogations of truths and ideas. In video games, there are people doing that work [of interrogation] but there also is a culture that says—this is just the game, it doesn’t matter. It’s entertaining, but we don’t have a commitment to telling the story right. Having created visual poetry means that I come to video games thinking that they’re equally capable of being art and equally important to get the message right and equally possible to hurt people without intending to.

What’s informing the way that I’m making video games is different than some people create games who say, “Whatever, you just shoot things.”I think there’s a smarter way of handling any kind of video game in terms of the humanity that’s behind it, as opposed to just the entertainment—that’s something that comes from poetry, visual poetry.

Sarah Mohammed (12) is the co-editor-in-chief of the Winged Post, and this is her fourth year on staff. This year, she is excited to help make beautiful...

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)