Humans of Harker: Speak up

Haris Hosseini starts the conversation

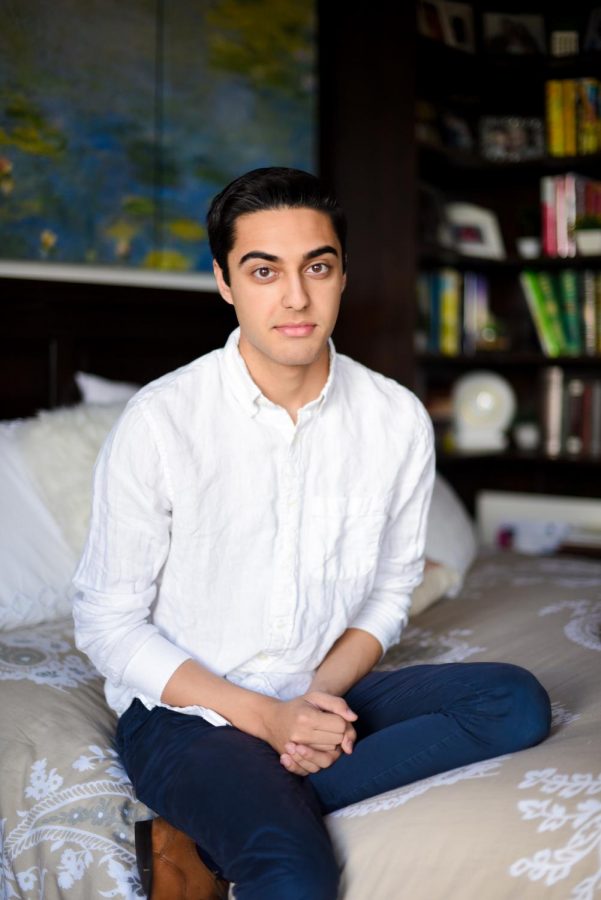

“Use your voice. Speak your mind, because that’s what this country is about, that’s what life’s about, that’s what our world has come to be about. Speak your mind, and listen to others. But vote—most importantly vote,” Haris Hosseini (12) said.

His voice resonates in the bright, open space of the athletic center as he strides across the gym floor before a sea of his peers and his teachers. He bears a stately confidence, looking up into the audience and holding their attention with ease and mastery. His every gesture, his every step and even his every pause is carefully calculated to support the message he has come to communicate—a message whose words land one after the other with gravity and precision, like darts on the bullseye of a target.

In fact, words seem to come effortlessly to Haris Hosseini (12). Whether it be before an audience of hundreds or simply with a friend in the hallway, he speaks with an eloquence that is simultaneously measured and natural. Such a combination rather embodies Haris’ nature as a whole—poised yet upfront, composed yet passionate, confident yet open to vulnerability.

But as Haris continues his speech, pacing up and down the length of the gym, one particular quality rises above the rest and distinguishes him as a speaker—his authenticity. Throughout his speech, entitled “The Man Problem,” Haris does not shy away from meeting the eyes of his audience as he tackles the problem of “toxic masculinity,” a societal construct of manhood that enforces ideas of “toughness” and violence as symbols of masculinity.

While that fearless authenticity translates into presentational charisma onstage, it is the product of a years-long journey of self-reflection and self-acceptance—a journey that, like many, saw its fair share of challenges and small victories alike, from grade school through high school.

“It took a lot of time and effort and energy to accept myself for who I am,” Haris said. “I’m still in the throes of that experience, but what high school has really taught me is to accept myself for the person that I am regardless of mold, regardless of what I’m told to be.”

Haris remembers his own struggles with the social expectations that come with growing up as a boy in America. As a child, Haris stood apart from the crowd: both his sister, Farah Hosseini (10), and his parents remember him as the boy who did not join the other children on the play structure during recess and rather stood on the edge of the blacktop, talking to teachers and reminding his peers not to run. His parents recall that when he was young, Haris was the sole student at his guitar recital to perform a 60s piece by Patsy Cline as opposed to the pop songs that were favorites among his peers. Haris was an “old soul,” his family liked to say.

“Haris has always been an adult his entire life,” Farah said. “Even at those earliest times, I knew the kind of person he was and how we wouldn’t have a relationship like normal siblings, because Haris was always going to have a mind where he’s like a forty year old trapped inside a young kid’s body.”

Haris’ uniquely mature sense of self often brought him into conflict with the norms of boyhood, leading him to question not just his [place among his peers] but his own identity as well.

“Growing up, I never fit the mold. I just didn’t. I tried, probably not very well, to fit the mold of what it means to be a boy, and I never did,” Haris said. “That led to really starting to find conflict with myself—who am I, and why can’t I fit in? Why am I different from other boys I see?”

He struggled with this internal conflict for years, living what he described as a fraction of himself, but with time, he came to find empowerment in his tight-knit family—particularly in the values that his parents have espoused and taught since Haris’ youth. When Haris was young, his father, Khaled Hosseini, sat down with both Haris and Farah for one specific purpose: to establish trust on the basis of honesty.

“Every relationship, it’s foundation is honesty,” Khaled said. “It’s something that I really appreciate because with both his sister and Haris, we’ve always been able to have straightforward conversations, even about difficult things.”

However uncomfortable and fearful it proved to be, Haris knew at heart that he could not escape the truth—and he took his father’s lesson to heart.

“Sometimes the truth is uncomfortable, and the truth is scary and the truth is not what you want it to be, but that’s the thing about the truth,” Haris said. “It’s very stubborn, and it always finds a way of coming to light.”

Honesty and truth have since become two central pillars around which Haris has strove to build his own life and character, from his work as a public speaker to his everyday interactions with friends.

“He’s one of the most upfront, real people I’ve ever met, and I think that honesty comes through because he is willing to be completely blunt about things that are bothering him or things that he needs to get done,” Meghna Phalke (12), one of Haris’ close friends, said. “That honesty fosters honesty around him.”

Though Haris settled into the habit of candor and authenticity in his conversations with friends and family, it took time before he was able to apply those values to his relationship with his own identity. With time and courage, he has gradually become empowered to embrace himself more truthfully, not only owning his individuality but also daring to explore new aspects of his identity.

“I’ve become accustomed to discomfort and confronting it and not just confronting it but embracing it with open arms, because I know discomfort, whether it’s in front of a room of people who are waiting for you to give a speech, or whether it’s front of a classroom who’s waiting for you to present something, or whether it’s telling your parents things about yourself you never wanted to admit—that’s where growth happens. That’s where life happens, that’s where you take leaps and bounds into your own future,” he said.

He took up the challenge of discomfort and proceeded to “put himself out there” by signing up for speech in his junior year. Although Haris did not participate in organized public speaking activities before, he was already familiar with the world of public policy. Both of his parents have been active participants in politics and vote in every election, and starting from a young age, Haris found himself drawn more and more to the world of current affairs and politics, whether it be women’s rights movements or Barack Obama’s election in 2008.

“I’ve seen him blossom into someone who is particularly interested about issues around the world, and that’s a real growth from when he was a child, when was just sort of this Curious George who wanted to know about everything and anything,” his mother, Roya Hosseini, said. “It’s just been an amazingly beautiful process, to witness the unfolding of who he’s becoming.”

Haris took an even greater interest in civic life during the 2016 election, which saw a presidential race between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. As the election escalated in rhetoric and partisan animosity, eventually leading to the victory of Trump, Haris found himself, as he describes it, “rudely awoken” by the discrepancy between the political reality of America and the values that he and his family, who are Muslim, uphold.

“[The election] got me thinking about what matters to me and what matters to my family and what matters to my friends and what matters to America, and it’s not harassment, and it’s not insults, and it’s not division and hatred and bigotry,” Haris said. “Those are not things that I identify with or that I think most Americans identify with. So it got me up. It got me talking.”

He volunteered for Hillary Clinton’s campaign and wrote essays about national issues, becoming an advocate for the vision of America that he believed in, and a year later, he joined the speech team and began his work in public speaking. That school year, he wrote and performed “The Man Problem” across the nation, receiving numerous accolades for his work and ultimately placing third in the nation at the 2018 National Speech and Debate Association.

“I always knew I had a lot of opinions and I liked expressing them, whether it was in the classroom, at the kitchen table, but I never had an outlet, a real formal outlet,” Haris said. “And then I found speech, and it changed my life. It totally, completely turned my life upside down because suddenly I was given ten minutes to speak about something that mattered to me and you had to listen. You couldn’t turn away—you had to listen to me. And that was awesome.”

Beyond just the expressive outlet that it offers for Haris to voice his opinion on issues that matter most to him, speech has also given him another avenue towards self-acceptance.

“When you have people telling you, ‘Hey, I heard you and your voice mattered and I care about you had to say and it touched me and it moved me,’ you think differently about yourself,” he said. “I became empowered because of that speech and this activity. I became the people I look up to, the people on TV or the people in my school or the people at home who I admire—I became them because I was able to say something and it mattered, whether that was a little or a lot I’ll leave to other people to decide, but it mattered. And that’s enough for me.”

In spite of the support and commendations that he has received, Haris doesn’t pretend that his arguments are always correct, and though he always takes a stance on any given issue, he opens himself up to the benefits that criticism and compromise can offer.

“I would describe myself as someone who is sometimes wrong and sometimes right, but always speaking his mind,” he said. “I’m opinionated, and by nature, I am often wrong. I think a big part of my life has been finding a way to express yourself in a way that accommodates you even when you’re wrong, even when your opinions are flawed or short-sighted.”

Haris applies that mentality of acceptance and adaptation to his work in speech, which he views as an instigator of constructive conversation between opposing viewpoints.

“If my speech could start a discussion, whether that’s ‘I hated it’ or ‘I loved it,’ if it can start a discussion beyond that to ‘I thought this because,’ ‘I thought that because,’ then I’m happy. You don’t need to agree with me. As long as discourse is occurring, then lovely,” he said. “Do I have an opinion on what the right side is? Sure, but that doesn’t mean I’m unwilling to hear the other one and adjust my views as necessary.”

For Haris, this aspect of discourse—the ability to stimulate new ideas and different perspectives—allows for not only a more complete understanding of the situation at hand but also a greater diversity of voices to be heard, both of which, in Haris’ view, are essential to life itself.

“You are never going to understand everything on your own. You’re never going to get life and get the world on your own. You must discuss with people. You must speak to people who’ve had experiences different from yourself,” he said. “That’s what’s important about diversity and representation in government, in industry. When you don’t have all the voices at the table, you cannot represent all the voices in the country.”

To advance his mission of representation, Haris hopes to empower the disadvantaged and lend an ear to the marginalized. With the encouragement of his parents, who especially value the idea that “the world is much bigger than their zip code,” as Khaled said, Haris has worked with numerous service groups, such as a local group in his neighborhood called Acts of Kindness.

In the past few years, Haris joined his father, who is a goodwill ambassador for the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), on three of his trips to Lebanon, Uganda and Italy, where Haris met refugees whose stories inspired compassion and empathy.

“Just in meeting with them and speaking with them, you understand that these people are not at all different than you. The only thing that separates you and them is misfortune and bad luck to end up in that region of the war at that time,” he said. “It gives you a profound look into the humanity of others that I think if more people could experience, we’d live in a different world.”

From listening to the stories of refugees to sharing his own story on the stage, Haris hopes to empower those around him with the same message that inspired him as a child, the same message that lies at the core of his vision of a diverse, open-minded and accepting America: speak up.

“I’ll continue to use my voice to speak out about things I care about, and I know others will do the same, and I think that’s the key to a better world,” Haris said. “That’s what it all comes down to—for us to see the humanity in each other, whether we’re oceans apart or a table apart.”

Kathy Fang (12) is the editor-in-chief of Harker Aquila. This is her fourth year on staff. From covering local marches and protests to initiating Harker...

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)

Sue Foltz • Mar 25, 2019 at 12:13 am

Haris- you will knock it out of the park in college!!

Congrats!!