Clothing brand American Eagle released an ad on July 23 where actress Sydney Sweeney crossed out the word “genes” in a billboard saying “Sydney Sweeney has great genes” and replaced it with “jeans.”

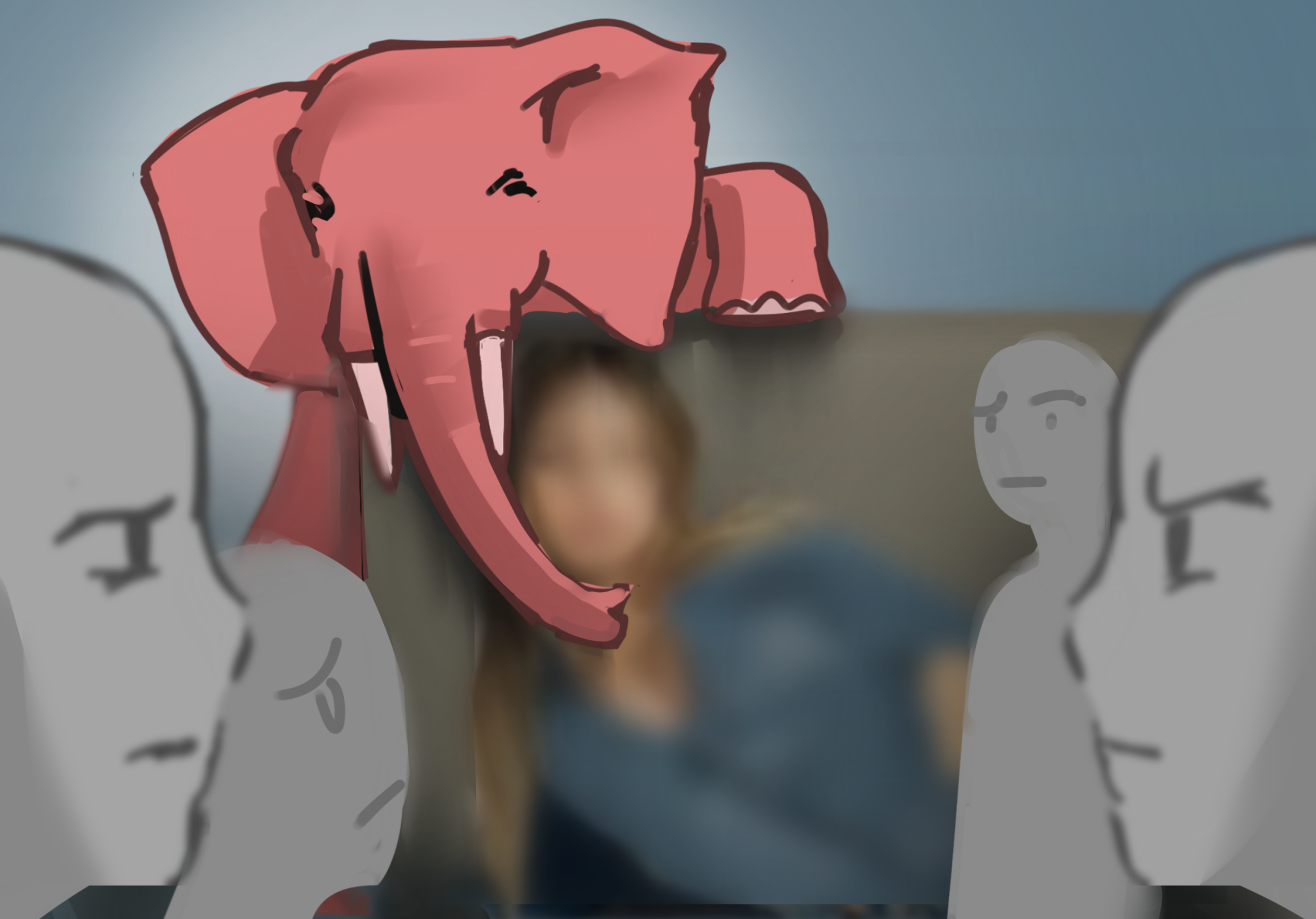

Many progressive internet users felt that this ad could be a dog whistle for white supremacist ideology. This belief stemmed from the emphasis on genetics as well as Sweeney’s resemblance to an Aryan ideal of beauty with her blond hair and blue eyes. Conversely, other netizens supported the ad campaign and opposed critics, leading to an increase in American Eagle’s social media following and stock price.

“The marketing perspective is that it doesn’t actually matter if they agree with what is being said — all that is important is it creates an emotional response,” DEI director Patricia Burrows said. “They want to create the largest emotional response regardless of the impact it has on society. That’s really dangerous; not so much the actual marketing message, but the why behind it.”

Brands like American Eagle could be inciting rage to spark engagement and drive consumers to their products. This tactic, called “outrage farming,” aims to deliberately provoke an audience reaction with the goal of increasing social media traffic.

The American Eagle campaign taps into a trend where brands blur the lines between product and political discourse. With the rise of social media, brands and political campaigns understand that emotional headlines and provocative imagery capture attention more effectively than thoughtful arguments, as algorithms favor content that generates high levels of user interaction regardless of whether the sentiment is positive or negative.

“In the past decade, we’ve seen a shift towards getting more information through social media than traditional news sources,” junior Siddhartha Daswani said. “Before, people would turn to publications like The Wall Street Journal or The New York Times, but now, social media is a dominant source, and that’s led to more emotionally charged, attention-grabbing content.”

Because algorithms make outrage a profitable marketing tool, subtle political messages spread throughout social media. Senior Joy Hu often sees these messages on her feed.

“The reason why social media political messaging is powerful is because a lot of the time it’s less overt, whereas for a political ad you would see the party and make a lot of assumptions,” Joy said. “It’s easier to absorb these subconscious messages. Every single time we open our phones, no matter where we’re looking, there’s often some sort of political subtext.”

Siddhartha notes the impact of this trend, particularly in how advertising increases the divide between both sides of the political spectrum in the U.S.

“Corporations care about making sales, not so much as the validity of the information that they propagate,” Siddhartha said. “People are being inflamed, perhaps even subconsciously through advertising, to feel very strongly about certain sides of things, which is prolonging and increasing the intensity of certain cultural conflicts. It’s a net negative on the ability of the U.S. to be a cohesive democracy, and it’s readily alienating the population into two halves.”

Instead of seeking out in-depth research or diverse viewpoints, people simply log on to social media to passively consume political takes that often align with their own beliefs. Systems where individuals are only exposed to information that reinforces their views amplify polarization. Now, people with extreme opinions dominate public discourse. While these systems allow outrage farming to sell products, they discourage the understanding across ideological lines that society needs.

“The world is very polarized,” Burrows said. “In public, we’re seeing these very messy and inflammatory discussions, and it’s turning people off from having conversations, which is so unhealthy because we can’t have a dialogue as a society about what is right or wrong. There are a lot of voices who are maybe more balanced, or who don’t know yet, but they’re afraid to say they don’t know.”