There’s no question that Harker is a diverse place. From the range of extracurricular offerings to our academic interests, each student is profoundly different from the next. Yet, there remains one staggering majority: according to Niche, the total student body is 73% Asian. White students comprise 10.8%, and multiracial students (many of whom are a combination of Asian and white) make up 10.5%. Single-digit numbers of students belong to Latino/Hispanic or Middle Eastern/North African communities in roughly each grade. For sophomore Babila Mfonfu, the difference is even more striking: per his knowledge, he is currently the only Black student in the upper school.

Various minority students and alumni interviewed for this piece remembered feelings of isolation during their time on campus. Students generally felt comfortable within the communities and friendships they created for themselves, but recalled feeling disconnected from the broader community at times. Babila said he feels people often make assumptions about him due to his background and questions whether they are genuine in their interactions with him.

“There are cases where [students] are clearly giving negative stereotypes,” Babila said. “Whenever I get a question that I feel like is arguing towards not me, but what people expect of me, I get really critical of the question before I answer it. I won’t just answer off the top of my head. I really think, ‘Are they asking me this question to be serious, or are they asking it to evoke a reaction?’”

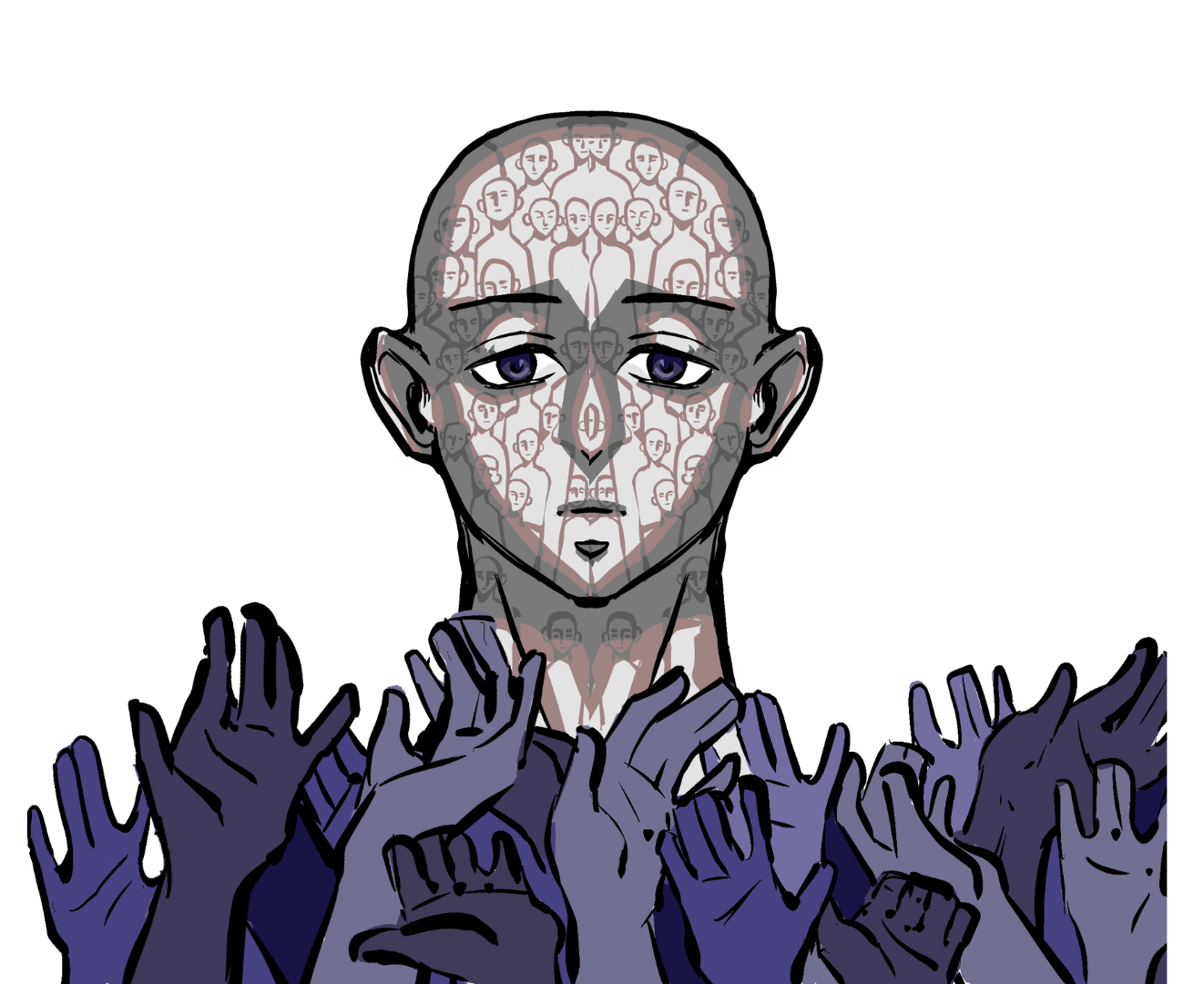

Multiple minority students also reported feeling spotlighted as the only person of their race in a room. Students can feel like spokespeople when they are many of their classmates’ only exposure to an ethnic group, choosing between advocating for their communities or falling under scrutiny themselves. One anonymous Middle Eastern student felt the limited diversity — and subsequent limited discourse — prevented them from safely embracing their identity.

“In general, just school culture is what makes it hard for me to exist and be open about my cultural identity,” the student said. “Just because I know the personalities and the people we have here and the amount of people who maybe wouldn’t want to keep talking to me if they found out I was [what I am].”

That’s not to say that the student body is solely responsible for these experiences. Many students cited dissonance between their perceptions of their time at Harker and the administration’s large emphasis on celebrating Harker’s diversity, from the annual Culture Week to Student Diversity Coalition announcements at school meetings. Multiple students recalled feeling that their lack of representation was overlooked or simply not talked about enough.

“I remember hearing [about diversity] and being like, ‘You don’t really mean that,’” Black alum Kai Stinson (‘24), who attended Harker from kindergarten through high school, said. “Just because white people are the minority at the school does not mean it’s diverse…Every time I would hear that, I was like, ‘Okay, you say that, but you’re not really doing anything to promote it.”

Many of the upper school’s efforts at promoting diversity exist through outward-facing initiatives, like cultural showcases. Some students, however, felt these programs compel students to take on the mantle of representing DEI, in place of the administration actually shifting the balance within the community. One anonymous Latinx student mentioned the use of photos from a ballet folklórico performance in promotional materials as one instance of this imbalance.

“There’s a lot of pressure from the DEI program,” the student said. “There is pressure because they need to show that they have diversity, but at the same time we’re treated as tokens.”

The administration admittedly faces a difficult task in parsing what minority students actually want in terms of support. Is it fair to single students out in order to ask them themselves? Or is it unfair to not? Upper school admissions director Jennifer Hargreaves, who acknowledged the incongruence between Latinx enrollment at Harker and the Latinx population in Santa Clara County, pointed to the difficulty in striking this balance.

“It’s sometimes tough because students at this age don’t want to be different from anybody else,” Hargreaves said. “But at the same time we need to recognize that everybody needs different things, and we want to make sure that we’re there to give a little bit more support in one area than another area depending on each individual.”

While the administration can never know precisely where a student falls on this spectrum, asking is the only way to find out. Some may decline opportunities to advocate, whereas others — like Babila — want the chance to be a voice for their community, and encourage administration to reach out.

“During Black History Month, there’s a whole presentation, but nobody actually bothered to ask me about if I even want to present,” Babila said. “I just feel like everybody at the school should have a chance to feel represented. If it were up to me, I probably wouldn’t reach out, because I wouldn’t even know some things might be happening. It would be nice to just be offered the opportunity, so that people can come and speak about their experiences.”

Part of this work involves creating more channels for communication between minority students and the administration. Affinity groups serve as one space for students to channel their concerns through people like faculty advisers, who can advocate on their behalf in meetings with upper level staff. But this is a less-than-perfect solution; for example, there is not currently a Black Student Union on campus, and there hasn’t been since 2023.

DEI Director Patricia Burrows, who is in her first year in the position, said that the DEI office is a place for students to express these concerns. The position of DEI director was created two years ago, but the DEI committee has existed since 2013.

“The channel should be that anyone can come by and talk to me, but this position is new, I think people don’t even know where this office is,” Burrows said. ”Just as the ASB is receiving information about how school is as a whole, people can come and talk to our diversity coalition officers in the same way…With SDC it’s time for some new rebirth and redirection.”

Other DEI work at Harker has involved the introduction of electives like Introduction to Ethnic Studies, Introduction to Social Justice: Methods and History and Social Psychology in 2020, as well as the diversification of senior English electives and reading materials. Still, interviewed students wanted representation beyond that of electives, such as in the broadly-defined frosh world history class or even as an addendum to popular AP curriculums.

This inclusion would encourage students to learn about communities beyond their own, and also send the message to minority students that their histories are valued here. Kai also wished the administration had been more willing to confront the difficulties of Black history, alongside celebrating its triumphs, throughout his time at Harker.

SDC Officer Elie Ahluwalia (11) said complex topics like global conflicts may be better addressed in a classroom setting, like in a history class.

“The thing that we’re trying to do is keep it positive,” Elie said. “I do want to talk about things that are happening in the world, but I think the easiest way to go about making students feel safe and seen at school is by uplifting the celebrations of their culture.”

Harker collaborates with several existing nonprofit programs to outreach to communities like the Latino population. In 2024, Harker started working with Breakthrough Silicon Valley, which arms primarily first-generation, low-income students with the tools to apply to college. Last year, Harker also became a sponsor for Greene Scholars, a program that supports Black students in STEM, by hosting their one-week summer institute programs. Burrows also stated Harker is involved with Private School Village, a parent-founded initiative aiming to “to positively transform the private school experience for Black and Brown families.” Burrows hopes these collaborations will help students envision themselves at Harker and encourage them to apply.

“It’s not just about who you’re admitting, but who’s applying,” Burrows said. “How do we get people to apply? To get people to apply, they have to know that we’re a possibility.”

Still, outreach efforts can fail to resonate with these communities. One anonymous student attended an event hosted by the Breakthrough program, and reported feeling frustrated by rules within their financial aid contract preventing them from discussing their offer with prospective students — who iterated cost of attendance as one of their primary concerns.

SDC adviser and Latinx Affinity Group adviser Jeanette Fernandez also encouraged conversation around socioeconomic diversity as part of the school’s programs to better support the transition of more diverse groups of students to the upper school.

“[The panel is] just getting the word out,” Fernandez said. “Doing a summer bridge program or something like that to get [underrepresented students] acquainted with the ‘Harker way,’ would help. Because I have seen in the past, students — not necessarily Latino students, but students of different cultures — can come in new to Harker, only to leave junior year or something like that because they’re still struggling with being a Harker student.”

That’s not to say that diversity at Harker is at all a “failure.” Many of the students interviewed for this piece acknowledged the immense privilege that is a Harker education, as well as its relative diversity compared to many peer institutions.

Further, it can be just as dangerous to homogenize the Asian majority as it is to overlook the other minority communities; every student at Harker is much more than their race, and each and every one of their stories is just as valuable and unique as the rest. But for those within these minority communities, it can be harder to understand that, when there are fewer visible models of success, or fewer avenues to feel connected with and understood by peers.

For those who do comprise this community, Kai encourages students to never back down from showcasing their rich heritages.

“I’d say: definitely embrace it,” Kai said. “I know I’m the only one, but I looked at that as a good thing, that I can represent what we are… Just try to be unapologetically Black in yourself, and that’s the best way to represent.”

Regardless of where they come from, every student can choose to actively confront their blindspots. Students can learn about histories other than their own, and be willing to listen when minority students take the time to share. It’s not enough to simply acknowledge our differences. We need to work to improve disparities, and at the same time, make sure we are equipped with the decency and empathy it takes to actually make these community members feel welcomed. Babila reminded that compassion is a small ask of our student body.

“Since Saratoga is predominated by a very small demographic of people, I feel like it’s asking too much of people to accommodate just because of me,” Babila said. “But I’d ask people to just treat me with respect like another person. I’m another person, too.”

Walang Abang • Apr 21, 2025 at 7:38 pm

What matters is coming out stronger in an atmosphere full of challenges. By the way, there is no station in life without challenges. Living in a diverse environment gives us an opportunity to be assertive in the way Babila suggests.

Boma Miranda • Apr 13, 2025 at 12:07 pm

This is incredible. So proud of you Babila👏👏

Nina • Apr 13, 2025 at 6:40 am

Excellent insights from Babila and everyone who shared in this article. Bravo!

Babila, thanks for reminding us all to show compassion, respect others, include people, and to practice genuine curiousity about the experiences of others.

Suzanne Rachel Ntsama • Apr 13, 2025 at 5:08 am

These challenges can feel even more difficult when faced with experiences of racism and isolation. Regardless of our different colors, white students and black students are all united as one. The key is to love one another. Well done Babila.😊😊