Deep dive into AI

Artificial intelligence represents the beginning of our future. Chatbots write papers and answer questions. Programs mimic the voices of popular celebrities. Advanced AI raises the question: what defines creativity or humanity? This longform seeks to address AI developments, the uncertainties behind it, and the technology’s widespread impact on our modern world.

From Chatbots that answer questions and write papers, to programs that mimic the voices of popular celebrities, original works face the risk of replacement as AI begins to fill every facet of our everyday lives.

Imagine Drake singing a K-pop song, or Ariana Grande lending her voice to a SZA track. With AI technology, these covers can be brought to life as AI-generated song covers. AI covers have taken over social media, replicating artists’ voices with such precision that the line between reality and AI grows increasingly blurry, and at times, almost impossible to discern.

AI covers first went viral on TikTok in early 2023. Today, the hashtag “aicover” currently boasts over 11 billion views on TikTok. Some of the most popular AI covers include Ariana Grande’s cover of the romantic, sentimental “Everytime” by Korean singers CHEN and Punch, Ariana Grande’s cover of the midtempo, bass-backed “Kill Bill” by R&B singer SZA and Drake’s cover of of the peppy, upbeat “OMG” by K-pop girl group NewJeans.

As the founder of Beats and Bytes, a club that combines AI and music, Saanvi Bhargava (11) has listened to AI song covers on YouTube and highlights their varying quality.

“It really depends on the song and how it’s generated,” Saanvi said. “There was a Playboi Carti cover of ‘Cupid,’ and you can really tell that it’s not his voice. But for other covers, like the Drake and the Weeknd cover of ‘Heart on My Sleeve’, you can’t really tell. So I think it depends on how it’s generated and for what purpose.”

The replication of popular artists’ voices sparked controversy among established record labels, such as Universal Music Group, which urged streaming platforms like Spotify and Apple Music to stop AI platforms from using their copyrighted songs. Despite their efforts, most record labels failed to protect their copyrighted music from AI cover platforms.

Violations of intellectual property had previously emerged as a topic of debate within school music groups, which often use copyrighted songs in their performances. Upper school orchestra teacher Jaco Wong connects this history to the current copyright controversies surrounding AI song covers.

“It’s been a long question even before AI and has been discussed since acapella groups have been invented,” Wong said. “Every college campus has many different acapella groups and you have many people arranging these Bruno Mars or Taylor Swift songs. Technically, they’re not supposed to, but Taylor Swift’s record company is not going to go after a random acapella group at a high school.”

Unlike acapella groups, AI song covers come from an entirely technology-driven process. AI song generators use an open source software called SoftVC VITS Singing Voice Conversion (So-VITS-SVC) to create the song covers. The software utilizes an AI-powered deep learning model trained by breaking down inputted audio into frequency bands, allowing it to effectively study the artist’s voice. The broken-down frequency enables the AI to transform various vocal recordings into the voice of specific artists. Beats and Bytes social media manager Bhavya Srinivisan (11) recalls her first impressions after listening to an AI song cover.

“It’s really cool to hear other artists’ voices on other songs,” Bhavya said. “You can kind of hear that it’s not them. But it’s really cool, and it’s something you wouldn’t imagine.”

Several platforms such as FineShare Singify have streamlined the process of generating AI song covers. Now, users simply have to select the voice of an artist and input an audio file to create a cover, and AI technology has improved to generate covers that sound increasingly realistic. Upper school computer science teacher Marina Peregrino acknowledges the increasing popularity of AI generative technology and expresses inhibitions about its new accessibility.

“We have this tool now, at an amazing level,” Peregrino said. “Talking about AI has been around for many decades, but it hasn’t been functional and useful until now. Now, it’s become much faster, and we haven’t quite integrated it into our laws or culture quite properly yet. I think we might be in for an upheaval right now because it’s affecting intellectual property, and that’s people’s livelihoods.”

With new AI tools hitting the market each day, the technology’s influence increasingly pervades the art industry, a largely human-driven enterprise. The surge in popularity of AI song covers then raises new questions about what the future holds for AI and music, and whether music will still continue to be a human-driven art in years to come.

“Tell me a fun fact about the Roman empire.”

“Recommend a dish to bring to a potluck.”

“Come up with concepts for a retro-style arcade game.”

These examples offer just a glimpse into the wide array of prompts users can submit to artificial intelligence language model ChatGPT.

Since its launch in November 2022, ChatGPT has sparked global debates as both a tool that unleashes new possibilities and a human creation susceptible to errors. OpenAI acknowledged several of the model’s shortcomings upon its release, including its occasional “plausible-sounding” but inaccurate responses, sensitivity to slight changes in user wording and tendency to repeat certain statements due to biases in its training dataset. Additionally, the model sometimes fails to detect inappropriate requests.

“ChatGPT is incredibly limited, but good enough at some things to create a misleading impression of greatness,” OpenAI CEO Sam Altman said, in a Twitter post last December.

Concerns about ChatGPT, particularly its potential to hinder student learning, have impacted education at the K-12 and university levels. For example, several public school districts including The Los Angeles Unified School District and New York City Public Schools banned ChatGPT usage on school devices and WiFi networks in January. Capable of generating human-like written responses in seconds, ChatGPT could discourage students from developing independent analysis and reflection skills.

“One thing we have to think about is, given where the student population stands, you have to build your own skills of critical thinking, writing and reading first,” English teacher Nicholas Manjoine said. “And then you can use tools like [ChatGPT] later on once you have more sense of, ‘okay, given my skill set, how can I use this in order to fast track?’”

Despite continuing concerns, schools have increasingly shifted towards incorporating ChatGPT in the classroom, with the New York City school district revoking their ban in May, and the Los Angeles school district loosening policies this school year. For one, banning AI at school gives an unfair advantage to students with personal devices and internet connection at home. Furthermore, as technology’s influence expands at an unprecedented rate, many educators believe that students should learn how to responsibly use these tools early on.

Harker reflects these evolving attitudes towards ChatGPT and education, with some classes allowing ChatGPT usage in limited scenarios. In AP U.S. Government and Politics classes, for example, students may use ChatGPT to “clarify uncertainties in course materials” or “inquire about specific topics,” though all submitted work must be written in the student’s own words. On the other hand, the upper school science department prohibits students from using AI as a reference source for any submitted work, due to the challenges of “cit[ing] or even know[ing] the sources of this information.”

“We’ve asked this platform to do all these things for us, so now we’ve got to ask, ‘how can we use it as a way to promote critical thinking?’” Manjoine said. “The writing style that ChatGPT promotes is sufficient but not very polished. And we certainly want to encourage all students to find their own voices.”

In this era of technological advancement, artificial intelligence is revolutionizing the workforce, even threatening to take over a majority of jobs. Yet few regulations exist in place to protect people’s data.

As only thirteen out of fifty states have passed comprehensive data privacy laws, our data remains susceptible to potential unauthorized access and misuse. Chatbots save every conversation to further train its model which could pose risks to individuals if it’s not carefully managed and regulated as all of its records available to humans for review.

Brittany Galli, CEO of Mobohubb, former CEO of BFG Ventures, and workforce management and member of the ASIS Women in Security Community, has centered her work around promoting the importance of data governance, data hygiene and consciousness.

“AI is taking in so much right now that there are no rules,” Galli said. “You have AI chaos because it can’t be organized. The faster we get it organized, the faster we figure out where the rules sit. The real danger is letting this go on too long without some sort of ground rules that everybody can keep going with.”

The lack of awareness and regulations from the introduction of AI exacerbates a long-standing problem of security breaches and unintentional disclosures of data. President of AI Club Aniketh Tummala (12) emphasizes these underlying issues, stating that the problem might be more dangerous than we are aware of.

“It’s regulated really badly,” Aniketh said. “For stuff like ChatGPT, companies can take all your personal information and throw it in their model and you can’t really do anything about that right now because it’s technically available. If someone wants to search ‘what’s my social security number?’, then the model would have access to that — it’s not protected.”

Exploitation of personal data can lead to manipulation if it falls into the wrong hands. People in positions of power can weaponize the deceptive neutrality and factuality of AI to manipulate the general public, utilizing knowledge about their interests, prejudices, and affiliations.

Dr. Julia Glidden, a member of the Board of Pivotl, a business intelligence consulting firm, compares the introduction of AI to that of social media. According to Dr. Glidden, we “sleepwalked” into social media: we focused only on the positives, which led to people using platforms without understanding the associated risks and potential harm. She now uses her platform to caution others against making a similar oversight with AI.

“That’s a huge black hole of a problem,” Dr. Glidden said. “We’ve been increasingly desensitized to the dangers of putting our data into the internet and not knowing where it’s going, not knowing who’s using it, not knowing the provenance of the data that we’re using. When you take AI and its ubiquitous accessibility, the ability for us to share data on an exponential scale and misuse data that has come from faulty sources is even greater.”

Companies used to pay hundreds or even thousands of dollars for personal data, but now people give their own data away for free. With the rise of social media platforms, people often post everything they do online, permanently putting their data onto the internet.

“Now people are even more unaware because they’re not even thinking,” Dr. Glidden said. “Our brain atrophies because we don’t have to use it; everything is automatic. We don’t know what’s happening to our data: we don’t know who’s using it and we don’t know whether it’s being used for good or nefarious means.”

Even more, the current landscape of regulatory policies remains barren due to the difficulty of passing comprehensive data privacy laws. Unable to keep up with the continuous advancements of AI, this lack of a legal framework leaves individuals with limited avenues to pursue in the event of data-related incidents.

“Legislation is a really big thing that we could be doing right now,” Aniketh said. “The European Union, for example, has really good data protection laws because they’re completely blacklisting all AI companies from using personal information, almost like giving consent. But the U.S. doesn’t have that right now and if we had that we’d be at least better off.”

Collaboration between corporations, the government and the public, is an essential part of the path to achieving a safe and fair online environment. This crucial redefinition of the relationship between corporations and the public begins with acknowledgment and awareness of the potential dangers.

“Governance standard, whether that’s an internal organizational governance standard or that’s a regulatory governance standard, [is where] we’re going to be headed there no matter what because we can’t all operate independently,” Galli said. “We have to eventually start working together and as a collective and operate by the same set of rules.”

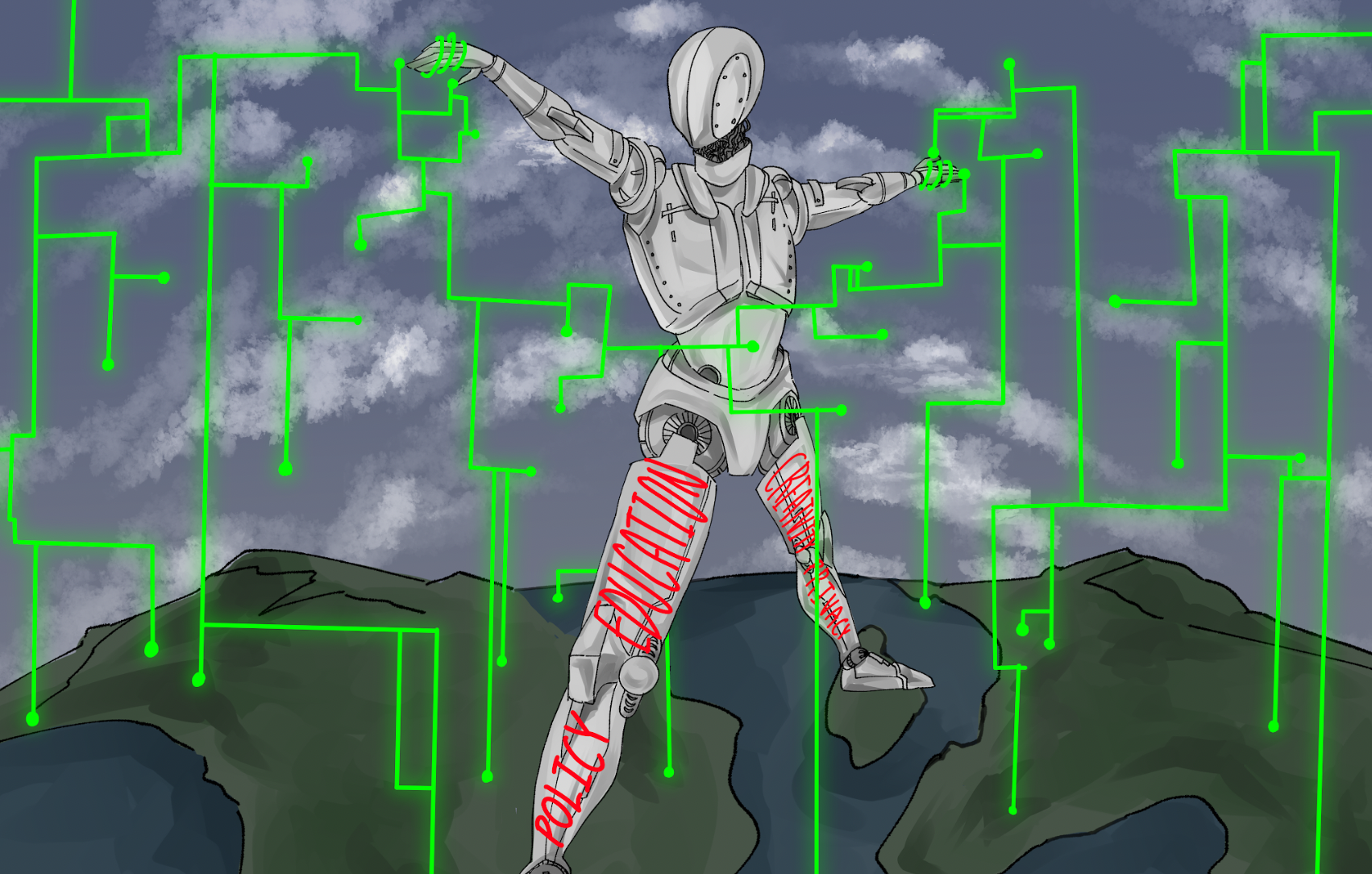

Concerns about an AI takeover or a world run by autonomous machines often frequent conversations on the future of AI. And as the rate of AI advances continues to grow, so do the stakes. But before we bow down to our new machine overlords, AI engineers point towards first refurbishing the AI development process.

AI ethics encompasses this goal, a field which seeks to promote the building of AI that benefits humanity. Ideals like transparency, sustainability, and equity all constitute the pillars of AI ethics, crucial in the quest to build better models. To actually achieve this more abstract aim, governments have turned to tangible regulation and policy.

“There have to be some sort of guidelines on designing AI, like the rules for your data and how they can be used and trained,” AI-interested student Nelson Gou (11) said. “Maybe in the form of excluding some of the data that lead to dangerous results or modifying models in certain ways.”

The Biden Administration signed an expansive executive order about AI on Oct. 30, 2023, marking one of the most high-profile AI policy moves in American history. The piece of legislation, the longest executive order ever issued, includes a wide range of initiatives about AI, with increased monitoring and demands for transparency for most corporate AI models. Concurrently, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer has held regular AI forums with high-level tech executives, the most recent occurring on Dec. 6, 2023.

“This is a great step because acknowledging that there is something that needs looking into is the first step,” upper school computer science teacher Anu Datar said. “I know that it’s very new, and a lot of people aren’t even really aware of how exactly it works, or what’s happening behind the scenes. Very few people in the world have the power to really control or make decisions about how this is going to impact the entire world.”

In similar fashion, European countries have also begun taking a stricter stance on AI. The EU reached a provisional agreement on its AI Act in December last year, establishing the world’s first comprehensive legal framework for AI. The law mandates that tech companies release details about their AI models to the government and adopt increased transparency in their development practices.

“Regulation is always playing catch-up to the technology,” Harker Dev President Kabir Ramzan (12) said. “So [regulators] don’t generally understand how the technology works fully when they’re developing these policies. So you’ll get these more broad ranging actions and statements that over time are refined. They’ll iterate and see how they can implement these regulations at scale and do that in a way that doesn’t stifle innovation.”

Since technological advancements are out of most policymakers’ field of expertise, regulation has often lagged behind the fast-paced developments of industry, a trend that has plagued policy for decades. In 1996, after years of monopolization in telecommunications, the Federal Communications Commission finally passed the Telecommunications Act, the first major overhaul of telecommunications law in over 62 years.

This delay in regulation also applies to AI, where effective policy has only begun to emerge despite years of rapid AI development. Given the slower upkeep, most AI policy espouses general ideals, like transparency and equity, rather than specific action items.

“I feel that there should be governance, there should be education, starting right from elementary school about what’s ethical and what’s not ethical with the use of AI,” Datar said. “And I think governance and regulation should cover all these aspects, and encourage the use of AI within those boundaries. That’s what I’m hoping for.”

With the promise of regulation also come concerns about proper implementation. AI regulation’s critics often highlight how ineffective policy might hinder new developments, jeopardizing the U.S.’ technological dominance on the world stage. While potential consequences exist in regulating AI, as the technology advances, many AI scientists cite regulation as critical to ensuring a sustainable AI future, a future which benefits humanity as well as innovation.

“It’s still unclear about what the future holds,” Kabir said. “I just hope that they will be able to sufficiently keep AI in check before it gets to a point where it’s too dangerous. And I think that’s the kind of the hope of starting these conversations.”