Follow life cycle of food

The bell chimes at 11 a.m. Within seconds, students flood out of their classrooms, all heading to one place: Manzanita Hall. Whether it be fan favorite California rolls from Chowda House or Chef Raja’s Indian specialities in Veggie Cafe, our daily dining comprises a memorable highlight of students and staff’s Harker experiences.

However, as we enjoy the diverse cuisines on our lunch trays each day, a key question arises: how does the kitchen feed thousands of students and staff each day? Is it done sustainably? In this piece, we examine the many ways we practice sustainability at Harker, exploring the life cycle of our food from farm to lunch tray.

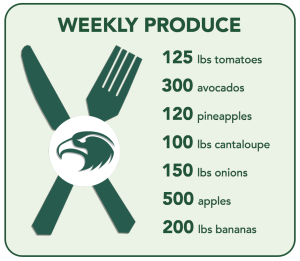

Every Monday morning, before most students even wake up for the day, trucks start to roll into the Saratoga campus. The cargo box opens up, revealing shipments upon shipments of fresh produce and meat.

The kitchen primarily sources from three main suppliers: Sysco, Performance Foodservice and BiRite. Harker also contacts companies like Bay Area bakeries Acme Bread Company and Sweet Production for breads and desserts and Pacific Harvest Seafoods and Allen Brothers for fish and seafood.

To ensure quality produce, Upper school kitchen manager Raelynn Baldwin relies on frequent communication with representatives from suppliers to stay informed about changing crop conditions like weather or disease.

“We have sales representatives who work with us in those companies so that we’re getting the best sources,” Baldwin said. “They send us email blasts all the time so that we know which crops are bad. We’re going through it with them like, ‘Watsonville flooded, don’t do strawberries for two weeks.’ Then we talk to their produce guys and make sure everything is coming in fresh and local.”

The seasonality of ingredients plays a large role in determining what to put on the menu. As a result, Baldwin relies on local farms as much as possible to ensure fresh ingredients.

“We try to get things as close as we can, especially since they call [nearby city] Salinas and around it the salad bowl of America,” Baldwin said. “We keep things seasonal because it helps with us trying to get things locally sourced. Since it was the end of summer, we’re starting to move from summer vegetables into fall vegetables, which are a little bit heartier and more earthy.”

In their commitment to supporting local agriculture, the kitchen staff partners with nearby farms in Watsonville and Gilroy, allowing them to gain access to high-quality organic ingredients like garlic or spinach. Although recent bouts of extreme weather prove challenging to this model and disrupt once-predictable seasonal patterns, Baldwin still considers seasonality the kitchen’s “biggest asset.”

One of the most impactful strategies the kitchen implements to reduce waste starts before food even arrives on campus: menu planning. Baldwin prepares menus as many as eight weeks in advance, outlining how food can be used most efficiently across stations. She strives to play to each of the chefs’ creative strengths when planning dishes, allowing them room to both experiment with unfamiliar cuisines and stick within their wheelhouse.

The chefs also keep notes on which dishes are most popular, trying to gauge how many servings they might need on any given day. After years of working with Harker students, Baldwin feels attuned to students’ typical preferences but still appreciates feedback on dishes.

“We get into a good rhythm, especially after the first month,” Baldwin said. “The first month is hard because freshmen are new, everybody’s coming off the summer and things are a little weird in the first few weeks, but once we get to a month, [students] have a rhythm and a flow and we notice it. It helps us to decide how we approach things.”

The physical preparation has been fine-tuned over the years, with batch cooking becoming one of the kitchen’s most useful techniques. Rather than preparing all servings at the beginning of the day, the chefs start with an approximation of how much they will need, and maintain backup batches on standby.

“Batch cooking is so that we know, ‘Hey, most of the kids got through [the line], we have 10 minutes, make some more,” Baldwin said. “If I put a popular thing in the main window, I’ll tell Mexican [Fiesta], ‘Hey, make a little less today, because it’s grilled cheese.’ We talk to each other to make sure that communication is key.”

Baldwin and the kitchen staff also work extensively with the Upper School Sustainability Committee to reduce waste, adopting new initiatives like low-waste packaging for field trips instead of individual bagged lunches and compostable cutlery in place of plastics. Sustainability Coordinator Andrew Irvine applauded the kitchen’s efforts but emphasized that addressing the biggest sources of waste at Harker ultimately requires greater student accountability.

“Logistically, [sustainable options] are a little bit more challenging,” Irvine said. “We do that with the context that we’re trying to impress the importance of sustainability and reducing waste. We’re so lucky to have one of the best meal systems, [but] because we have so much variety, students don’t think about [getting too much food.]”

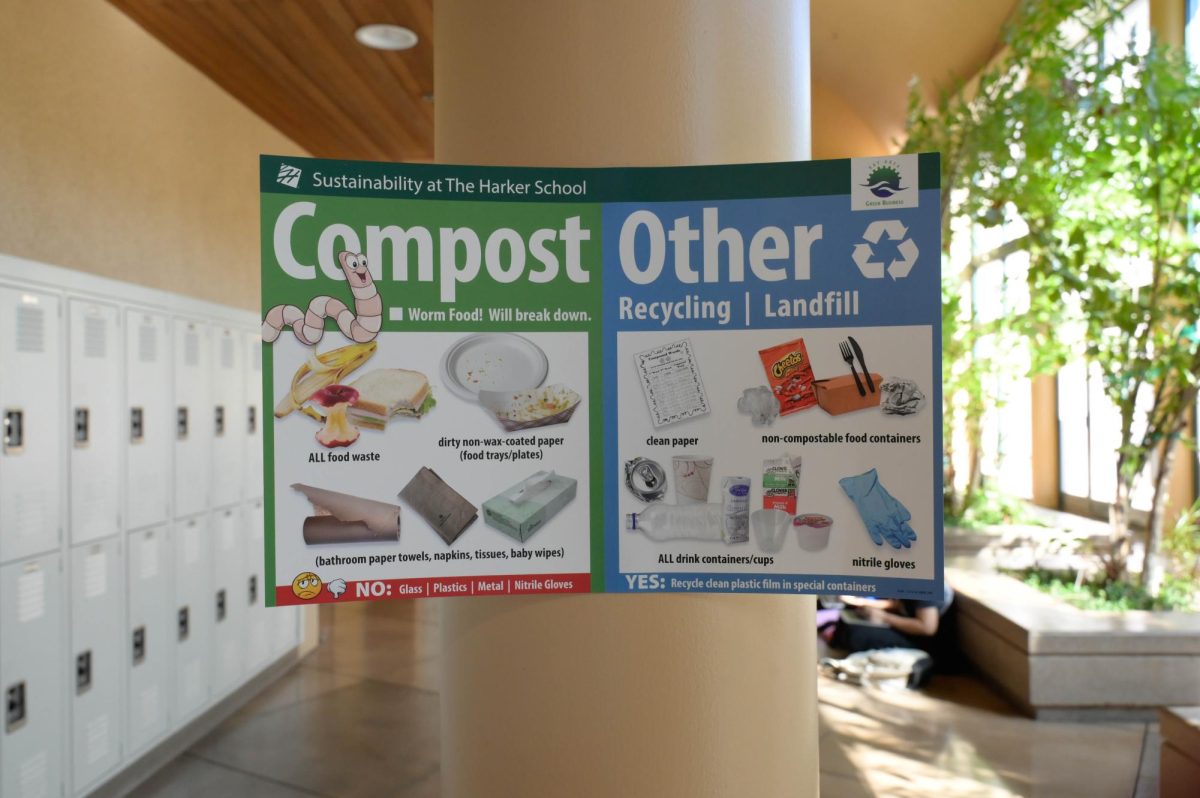

At the end of every lunch period, the final stage in the life cycle of food at Harker comes to fruition: disposal. With over 1,000 students and staff at Harker, leftover food and other waste quickly accumulates in the over 25 garbage cans dot the campus.

To allow for a more efficient and sustainable disposal of trash, the bins are categorized into compost, recycling and cardboard. The grounds crew typically empties the bins on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays to keep up with the large volume of waste, making extra accommodations for large events on campus.

Each bag of trash weighs approximately 10 to 15 pounds, which the grounds crew sorts through to ensure recyclables are correctly categorized. For the paper bins, the ground crew breaks down large cardboard pieces to save space. The trash bags then go to the dumpsters behind Nichols Hall, after which city services handle the rest of the collection and disposal process.

“[With] recycling, we do our part just by making it easier for them to identify what’s sorted,” Facilities and Grounds Crew member Elidio Espinoza said, highlighting the various ways trash is sorted at Harker. “This way, [the city can] take it from there.”

The efficient and environment-friendly disposal system at Harker helps minimize food waste. In August 2024 alone, the Saratoga campus produced 8 cubic yards of “wet” waste per week and 16 cubic yards of “dry” waste per week, with an additional 8 cubic yards per week recycled.

However, composting and recycling can only do so much: effective sustainability also requires mindfulness from students and staff alike.

“I see a lot of people getting a tray full [and] eating half of it and throwing the rest away,” senior Kyle Li said. “It’s a mindset; you can grab a bunch of stuff on your first visit and not need to go back, and then just pick and choose from what you have and toss the rest you don’t want. It’s definitely a problem.”

Green Team Co-President Shreyas Chakravarty (12) urges students to reconsider their attitudes towards waste. Given the kitchens’ hard work to ensure efficient food use, student buy-in poses a final obstacle to fulfilling Harker’s green goals.

“The problem is intentionality,” Shreyas said. “People are running off to lunch, they’re running off to office hours, and they just see a trash bin and they throw things there. If we were just a little bit more conscious, we could definitely find a way to reduce it.”