American Party System, Take Six

January 6, 2019

Nov. 6, 2018—the fated, long anticipated Election Day—came and passed in a flurry of red and blue. Voters around the country trickled into the polls to register and cast their ballots, newspapers and broadcasts ran nonstop programs and the nation held its breath in anticipation of the final results: Democrat or Republican?

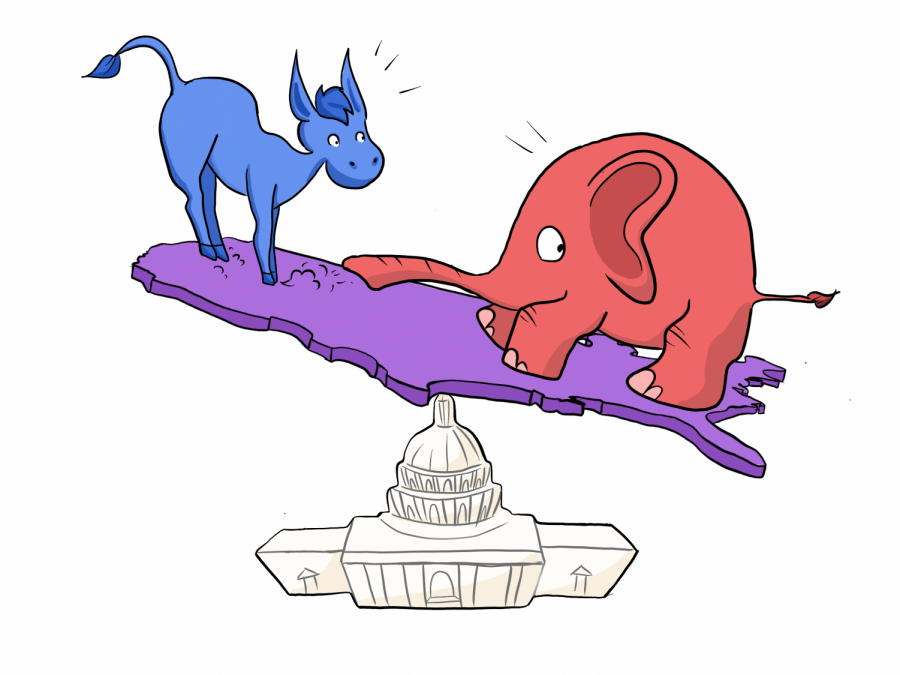

At the end of the night, it all appeared fairly simple, at least on the charts. Democrats gained a majority in the House. Republicans won more seats in the Senate. Neither side won an absolute victory, which, for the moment, made sense, but for the most part, both sides celebrated their respective victories, and each called it a successful election for themselves, choosing to disregard the pressing future of a divided Congress.

That was nearly two months ago, before the absence of a clear dominant party brought the government to a partial shutdown just in time for the new year.

But as 2019 welcomes those officials whom we elected in November into their respective duties—officials who might bring in an even more divided government than the one we watched come to a halt over winter break—we are brought to reckon with the new political landscape that we have created for ourselves and to ask, what next?

If the midterms are to be analyzed as an appraisal of the current administration and a forecast for the coming presidential election, as they more than often are, these election results provide no clear answer for either party. While the Democratic Party did secure important victories in toss-up elections, collecting 39 House seats from districts that were once Republican strongholds, the so-called “blue wave” faced a considerable check in the Senate, where Republicans snatched victories in states like Texas and Missouri, thus leaving us only a vague portrait of a divided future.

Out of all the lessons learned on the night of Nov. 6, the most notable takeaway from this round of midterm elections—and perhaps the most nonpartisan, universally acknowledged takeaway—is marked in the increased voter turnout, especially among 18 to 25 year old voters. Exit polls published by ABC marked a two percent overall increase in young voters from 2014, and early voting polls in individual state reports show even more marked surges, with early voting among young voters in Texas and Nevada surging by fivefold, according to a report published by The Hill.

And as it seems, with new voters come new values. Of the officials elected to Congress are the youngest woman, the first Native American woman and the first openly bisexual Senator, just to name a fraction of the records broken. With so many glass ceilings shattered in one election, it’s easy to believe the notion that a new political age is coming, one in which the younger generation and minority groups find themselves more and more at the center of the electoral focus.

While such a transition would certainly bring new perspectives and hopefully new solutions to the table, the persistence of a divided legislature seems to speak to an underlying, larger problem, one that we saw in its full glory, or its full terror, in the weekend before Christmas—that of the uncompromising two-party system.

Black-and-white—or really red-and-blue—politics aren’t new to Capitol Hill, or even to worldwide governments as a whole. The very nature of a yay-or-nay vote seems to require the division of the electorate into two camps on each issue, and gradually, these camps solidify to fit party lines, building a dichotomy of ideals that are forced to run head-to-head on most of the country’s biggest challenges.

More than often, these parties come to fall short of their obligations to the people as they come to fossilize around party lines rather than individual stances. Instead of voting measure to measure, issue by issue, politicians align themselves with a set compendium of opinions, half of which are formed not by vision but by mere opposition to the stance of the other camp. When such a voting trend comes to realization, it’s all too easy for lawmakers to clash and screech to a standstill when policies don’t align perfectly with their party agendas. After all, party tribalism and ideological obstinacy go hand in hand—without one, we wouldn’t have to deal with the other.

Though it sounds impossible at first mention, such a political vision—one free from party dichotomy—isn’t a political environment that’s entirely out of the realm of possibility. Starting from the Constitution and running through Henry Clay to John McCain, our nation has a long list of precedents for compromises and agreements between the parties that, though sometimes ineffective, have breached the party divide multiple times, often in urgent situations of dire stakes—such as the climate we see now.

Many sociologists and anthropologists categorize human society as innately tribal and hard-wired to separate into two camps set to forever hate the other, yet in spite of our proclivity towards tribalistic polarization, we are not forever bound to stay in the same dynamics that we built for ourselves decades past. Rather, human society is just as innately prone to adaption as to faction, if not more: When our environment changes, so must, and so will, we.

Take November’s elections, for instance. It’s no coincidence that this election, along with other recent elections, saw an uptick in young voters and “radical” nominations (first female presidential candidate, socialists and neo-Nazis, Donald Trump, etc.). The modern era is changing rapidly, with new technology and new ideals, and the electorate is looking for someone and something new to fit the demands of their twenty-first century society.

Yet the parties of decades past—that of the Democrats and the Republicans, the blue and the red—have not changed. Our government, in spite of the recent surge in the election of younger representatives, is still run by long-standing, established, and traditional politicians who are arguably still stuck in the past, unable to reckon with the reality of modern issues, including, but certainly not limited to, questions of data exploitation and technology misuse.

Such a political trend of tradition in place of, or perhaps dominating over, innovation then begs the question: Is our party system malleable enough to keep up with the times? Or are we to be forever stuck, as we were this winter, in the model of the past? Is our party system just to be as it is—antediluvian in its unbending dichotomy, unable to haul itself from the pull of antiquation and inefficacy?

James Madison would hope not. As written in his “Federalist 10,” the Constitution protects against the exploitative dominance of any one faction, or any one party, simply by its nature as the doctrine that governs an expansive republic: In his theory, a large republic should and will inevitably accomodate a large variety of opinions and parties, thus ensuring that “the increased variety of parties comprised within the Union, increase this security,” or the security of the public good. Madison did not envision a rigid bipartisan structure as the one we see today. Instead, he sought to lay the foundation for a fluid system that would serve the interests of the masses, primarily with the insurance of diversity of party.

And it seemed, at least for a while, that Madison was right. After all, our party system hasn’t always remained so fossilized—or even so red and blue. In the past, the party system has always adjusted itself and morphed itself to fit the needs of the present nation. At the beginning of our nation, the question of the constitutionality of a national bank dominated the first party divisions, from which emerged Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson in the 1790s, the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. Then, as the country fell into the rhythm of democratic self-governance, the conflict shifted away from how the government should function to who it should function for; there, we see the rise of Andrew Jackson and the Whigs in the early half of the nineteenth century. After it became clear that the influence of the masses wasn’t waning anytime soon, given the success of Jackson’s populist tactics, the debate about slavery quickly rose to the foreground and peaked in the 1850s with the rise of Abraham Lincoln, along with the realignment of the Democratic Party to stand in opposition to the Republicans.

These two parties—the Democrats and the Republicans—would persist, at least in name, for the remainder of American history into the present. Their core beliefs continued to shift according to the issues of their day, first in the late 1890s, when progressivism first saw its emergence, and again during the Great Depression, with the rise of the Roosevelt among the Democrats, who then recalibrated their values to match those of American liberalism.

While historians and political researchers debate the timing, as well as the existence, of a Sixth Party System sometime in the later years of the twentieth century, our parties have largely remained the same since Roosevelt’s day, with new issues sliding into the foreground here and there but no significant shift of values or representation.

What, then, should we draw from all that history? Well, if we put these party system on a timeline, it doesn’t take a historian to figure out that the Fifth Party System—the current one in power—has outlasted all the others and is, in fact, more than double the lifespan of any of the previous party systems. For a nation only 200 years in the making, one that not only is known for fast-paced modernization but has stood at the vanguard of modernization across the world, we cannot—and should not—expect a party system from 85 years ago to stay relevant, much less continue to serve the people as it ought to. As a result, while society and technology have advanced, our politics have trudged slowly behind.

To say the least, we need our current parties to wake up to the reality of the nation they have been charged to govern. To say what must be done, we need a new party dynamic that can tackle the issues at the heart of modern-day society—a society much changed from that of the 1930s, when our current party system initially took shape.

So, at the end of all this, what’s next? For one, our nation must now face the reality of a divided government and confront the greatest challenges of its current bipartisan system. With the shutdown at the close of 2018 haunting their every move, lawmakers across Washington, D.C., ought to know better than to keep so stubbornly to party lines and can reach across the aisle to work against the fossilization of red and blue camps across the nation. Only then can our government hope to fulfill its proper role, and only then can we begin to unravel the problems that plague our current society.

Finally, one word, and hopefully one that you’ve heard too many times—vote. Vote not by party but by belief, not by rhetoric and tribalist loyalty but by who and which vision you believe we most need to lead our country. Don’t underestimate the power of primaries and party caucuses as a means of electing leaders who represent values that are important to you and who can begin to redefine what our nation stands for. Force the politicians of our day and the representatives of your region to reckon with the issues of the current age, starting from a grassroots level, and work gradually towards the emergence of a new party dynamic that will be able to confront the prevalent challenges we as a nation face.

To those who voted on Nov. 6, your ballot helped shape the numbers we see today, and though they do set the stage for a divided government, those numbers represent a larger picture that signals the need for a more efficient party system. To those who have yet to vote, we look forward to—and absolutely depend on—hearing your voice in two years, when hopefully that new party system, one representing something closer to Madison’s republican vision, can start to take shape.