‘It’s about the culture, it’s about all we bring to this country’

Celebrating Hispanic and Latinx Culture with joy, community and color

June 2, 2022

“Let’s head over to Manzanita!”

As the last note of the bell rings, students pour out of second period, rushing from buildings across campus to the cafeteria. Chatter fills the air as a long column forms in front of upper school dining hall, spilling out underneath the archway adorned with the words “Manzanita Hall” stylized in bold black cursive. Nearly everyone on campus speaks the cafeteria’s name daily, and in doing so, they are referencing an aspect of Hispanic influence present on campus. The word “manzanita” originates from manzana, the Spanish word for apples.

Fresh Mex, a station in the Auxiliary Gym, offers popular and beloved meal options inspired by Latin American cuisine that Harker students consume by the platefuls daily. Influences from the Latinx heritage of the Bay Area, and California in general, pervade our campus life.

Both Hispanic people, those who speak Spanish, and Latinx people, those of Latin American ethnic origin, have deep roots in California, starting with Spanish colonizers who imposed the language to the native population in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Starting in the 1990s, migrant workers from Central America poured into the U.S. to work farms and bolster California’s rich agricultural sector; the community is well-established today.

According to July 2021 census data, 39.4% of Californians, or 39.2 million people, identify as Latinx and 25% in Santa Clara County identify as Hispanic. Yet Harker’s student body and faculty do not fully reflect this statistic. Only 30 of 1,926 students, or 1.3% of the student population, across all three campuses identify as Latinx or Hispanic, according to Admissions Director Jennifer Hargreaves.

“You could count on one hand probably how many Latinx students we have in the school, and for faculty, I could probably name them,” said Modern and Classical Languages Department Chair Abel Olivas, who identifies as Latino.

Despite their small number, Harker’s Latinx population continues to display the rich layers of their culture. Through hosting events such as La Noche Cultural last month and celebrating Hispanic Heritage Month from Sept. 15 to Oct. 15 with special dishes at Fresh Mex and paper decorations on bulletin boards around campus, they’ve allowed the larger Harker community to sample the vibrant art and accomplishments of Latinx and Hispanic people.

Weaving together Hispanic culture and art in a lattice of traditional ideas and modern designs

Upper school art teacher Pilar Aguero-Esparza, who identifies as Chicanx, remembers placing leather strips on a table as she contemplated what color to paint them. Once she painted the pieces, traditionally a shade of brown, she would weave them into a lattice that echoes a pattern often affixed to the base of a shoe, called a last. Suddenly, the need to buck the conventional color scheme gripped her.

“I needed to paint a different color,” Aguero-Esparza said. “I saw this bottle of sky blue sitting on my shelf, and I was like, ‘It’s gonna be that color because I really want to do it, and it’s so beautiful.’”

Aguero-Esparza’s fascination with fabricating these sandals stems from the traditional footwear donned in Mexico. She learned and practiced fashioning sandals in her parents’ shoe repair shop located in Los Angeles where she grew up. As a result of her parents’ shoemaking profession, she later found herself creating these sandals in her art studio while adding her own artistic spin on them.

“I said that I would bring the materials back to my studio and start making art with them,” Aguero-Esparza said. “My first impulse was ‘Can I design shoes?’ Since some of these were my own designs, I thought, ‘How can you use weaving and leather to make more contemporary stuff?”

Many of her two dimensional art pieces feature woven leather patterns, and much of her artwork incorporates her familiarity with shoemaking, knowledge passed down from her family. Although she experiments with bright colors, the traditional range of brown hues in her art prompted her to explore how these colors connected to themes of skin tones and race.

“Leather comes in all these natural colors like browns and beiges, so I found myself looking at that,” Aguero-Esparza said. “There was a lot of convergence happening not only with the materials I’m using, but also the ideas about skin tone and race.”

Her mural project displayed at an exhibition a few years ago integrated her ideas about skin tone and race. Using melted crayons, Aguero-Esparza created molds of her then 10-year-old daughter’s feet in the different shades featured in Crayola’s multicultural crayon pack. In her mural, strips of color streaked the wall, each pertaining to a shade represented in the pack, and each pair of feet rested under their respective colors.

Aguero-Esparza hoped that this piece would allow her daughter to explore the concept of skin color. When her daughter turned 18, Aguero-Esparza redid the plasters with her daughter’s feet in different dance positions to reflect the latter’s love of dancing.

“I was kind of curious,” Aguero-Esparza said. “I was thinking about what color she would think her skin is, so then I cast each color in the pairs of her feet so that’s what’s here at the bottom of the skin tone mural. Ten years old is young, so when she was 18, we had a lot of different conversations because she was a lot older. We talked a bit more about ‘Well, what is your identity in terms of your skin color?’”

These art pieces, both the one of her daughter at 10 years old and at 18 years old, will be displayed in the Lawrence Arts Center in Kansas this coming summer. The showcase specifically requested Aguero-Esparza’s project since the theme of the exhibition is parenthood, so the projects will be placed in proximity to each other as the juxtaposition will provide a sense of time passing by.

“When I wanted to cast my daughter, I said that it’s got to be her feet,” Aguero-Esparza said. “My parents were shoemakers, so people might say that’s so obvious, but I didn’t even think about that. I just instinctively did it.”

Social issues complicate relationships to the Latinx identity

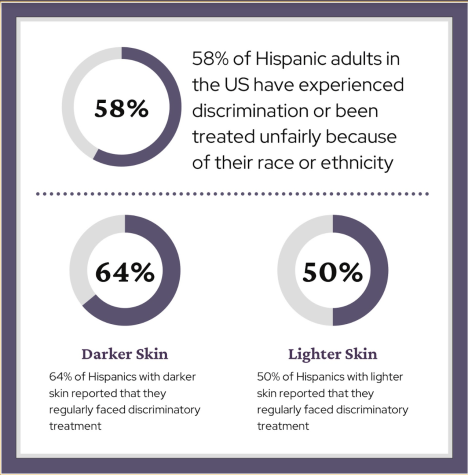

According to a 2019 report by Pew Research, over 58% of Hispanic adults in the US say that “they have experienced discrimination or been treated unfairly because of their race or ethnicity,” a statistic that varies in proportion with the darkness of a person’s skin color.

Mistreatment may entail racial slurs, jokes, belittlement or threats to personal security, as reported by the participants in the survey. Such discrimination happens too close for comfort — in California, and even to some members of the Harker community.

Fifty percent of Hispanics with lighter skin reported that they faced discriminatory treatment “regularly” or “from time to time,” compared with 64% of those with darker skin. Joanna, who describes herself as “white-passing,” acknowledges the benefits of her lighter skin tone.

“[Being white-passing] has made it so I can connect with my culture without ever having to worry about a stranger commenting on it,” Joanna said. “It’s something that I am fortunate that I’m never going to have to deal with because I get white privilege. It’s made it a lot easier for me to connect to my culture because I know that I’m never gonna have to deal with the barrier of society, [but] I feel for a lot of people who have to deal with it.”

Sara’s family recently requested an appointment at the veterinarian for their ill dog. When her father spotted a nurse and asked for assistance, the nurse rebuffed him, incorrectly assuming a language barrier was present.

“My dad has a pretty clear accent, but you can understand him,” Sara said. “The nurse that we were talking to was acting like she couldn’t understand him, and he was being very clear. He was like ‘No, no, I’m speaking English’ because then she started saying, ‘Do you speak Spanish? Would you like me to talk to you in a different language?’ I think he felt uncomfortable.”

Socioeconomic perspective on Hispanic life in California

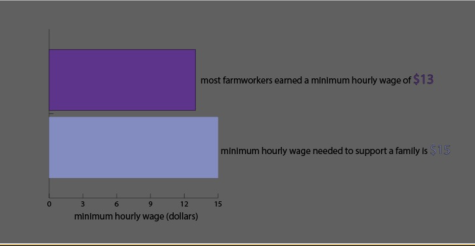

Additionally, the lack of protection for employed manual laborers disproportionately affects Hispanic and Latinx Americans. Fifty-one percent of hired farmworkers are Hispanic, and migrant workers constitute 5% of this group.

Rachelle Escamilla, a Chicanx poet residing in Monterey and former Library of Congress (LOC) Scholar, worked as a picker in the apricot orchards during her summers as a child. Her older family members’ livelihood centered around manual labor jobs, and she spent her tenure as a Scholar transcribing a testimony her grandfather gave in favor of migrant rights.

“My grandfather was a campesino [a farmer] who had three children die of malnutrition because the farmworkers at the time would pick the food for everyone else but didn’t have enough money to actually put food on their own tables,” Escamilla said. “Every piece of vegetable that is eaten by anyone in California is picked by a Latinx person, and that, to me, is most important, because migrant workers still don’t have the same rights and access that they should have.”

In California, the minimum hourly wage for farm workers ranges from $13 to $14, which is less than the $15 hourly wage that would best support the higher cost of living in-state. Especially during the pandemic, many workers found themselves without the safety net of long-term employment, access to medical care and PPE, or housing.

The term “Hispanic” refers to people with origins in Spain while the more expansive term Latinx that arose in the last 20 years encompasses those who do not have roots in Spain or do not speak Spanish, and Chicanx is used for people with Mexican heritage. Though Hispanic Heritage Month is intended as a time for celebration, naming it so exclusively raises eyebrows as to who, exactly, is celebrated.

“I think probably one of the things that has always been very perplexing is the term Hispanic,” Aguero-Esparza said. “Growing up as a Latinx here in California, the term Hispanic was not one that was utilized. I think it is more about trying to be broader in terms of who fits into that — who gave us that term? Do we call ourselves that or not?”

For Eileen Hernandez-Cuellar, a poet based in Los Angeles who identifies as Mexican-American and Chicana, umbrella terms such as Hispanic raise similar questions about identity and representation. To her, Hispanic Heritage Month, which occurs in the fall and aims to celebrate Latinx culture and contributions, has a flawed name but remains a vital opportunity to appreciate the resilience of her community.

“The word ‘Hispanic’ is European, it’s a Eurocentric word,” said Hernandez-Cuellar. “I really don’t acknowledge when people call it Hispanic Heritage Month because it seems a little ignorant to me. It doesn’t feel special, it doesn’t feel inclusive. [Still] let’s have a parade for Latinx Heritage Month, let’s take into account how important it is to recognize the month and just be proud of who we are.”

Harker’s efforts and projects to improve Latinx inclusivity and representation

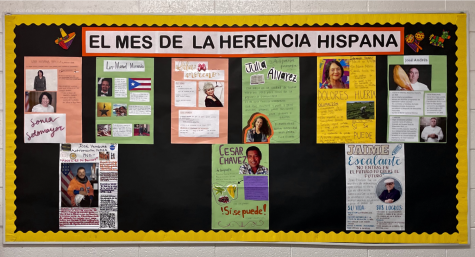

“Sí, se puede!” exclaims a medley of green, orange and yellow student-made posters scattered across a bulletin board. Swooping calligraphy and bold fonts on each poster draw the attention of viewers to famous Hispanic figures such as César Chávez, a civil rights activist born in San Jose who, along with the also-depicted activist Dolores Huerta, used the three-word motto as a rallying cry to lobby for farm worker rights in the U.S. Other vibrantly-colored posters chronicle the lives of individuals like Sonia Sotomayor, the first woman of color to sit on the Supreme Court and Julia Alvarez, Dominican-American poet, novelist and essayist. Bold black letters outlined by a vibrant orange border spell out “el Mes de la Herencia Hispana,” or National Hispanic Heritage Month. Assembled by Hispanic upper school Spanish teacher Carmela Tejada and created with her students’ and upper school Spanish teacher Diana Moss’s, who identifies as Hispanic, posters, the display remained in a hallway in Main until Oct. 15 to celebrate achievements by members of the Hispanic community.

(Kinnera Mulam)

The board is part of a festive effort to expand the presence of Latinx culture at Harker, which currently has a small Latinx population. In the Latinx affinity group, Jacob strives to recreate the same feeling of community and connection he experiences while spending time with his family.

“Not only are there so little Latinx students at Harker, a lot of the Latinx students feel disconnected from the rest of the student body,” Jacob said. “In other places, I don’t really feel Mexican, but when I’m with family or the Latinx [affinity] group, I feel like I have a little bit more to me. I feel like I can say stuff in Spanish and feel more comfortable with it than in a Spanish class. The [group] welcomes culture into our community.”

Harker staff and administration has worked to improve the inclusivity of underrepresented groups in the student body through the creation of the Latinx affinity group and Black Student Union last year by the Student Diversity Coalition (SDC) and the Faculty/Staff Diversity Committee. SDC was founded in the summer of 2020 by Natasha Yen (‘21), Brian Pinkston (‘21), Dylan Williams (‘21) and Uma Iyer (12).

The Latinx affinity group held its first meeting of the school year in September 2021, where the club advisers and students introduced themselves, discussed decorating a bulletin board in Main that featured Latinx artists and engaged in lighthearted conversation. Sara, who attended the meeting, appreciated the safe space provided by the group.

“I really enjoy just talking to them about where we’re from, what we enjoy to do and all that because it’s just a nice, small area to talk to people,” Sara said. “It is a nice place to relax and talk to people who have similar experiences to yours.”

The upper school Spanish department designed and launched a website 15 years ago called “Pórtico” that featured student-made projects about topics related to the Spanish-speaking world, providing a way for students to both learn more about the culture and educate others about their findings. Members of the Spanish National Honor Society compose these pieces in Spanish based on a self-selected subject matter. The website accepts a wide range of topics, from food reviews to celebrations to issues regarding the Latinx community, and the projects can consist of articles, reviews, interviews, photos or videos. Initially a physical newsletter, the site has evolved to a website with hundreds of projects, and the Spanish department publishes around 30 pieces each year.

“We were thinking about the activities that we could do with our Spanish Honor Society by making something that they can explore and that can also be used by some other students,” Garcia said. “It’s really an endless collaboration.”

The Spanish department, led by Tejada who created the bulletin board, integrated the celebration of Hispanic Heritage Month into their curricula. Moss designed an annual project in which her students will exchange short videos with students at El Colegio San Ignacio de la Salle in Quillota, Chile. Moss’ students filmed recordings featuring their own family traditions which were then sent out in late September 2021 to the students in Chile, who responded back in a similar manner a few weeks later.

Student-led clubs at the upper school also organized events and led initiatives in celebration of this month. With the help of Goodreads and reading challenges on Twitter, the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) Book Club organized a list of literary works rooted in Hispanic culture to share with its members, who then voted to discuss “I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter” by Erika Sánchez on Oct. 8, 2021.

The Spanish National Honor Society hosted La Noche Cultural at the upper school in March to celebrate Latinx culture through performances from current Spanish students, who sang Spanish songs such as “Dos Oruguitas” from Disney’s” Encanto,” acted in skits of shows such as “Caso Cerrado” and indulged in food such as tres leches cake. The night concluded with the annual salsa dancing competition that allowed attendees to engage in yet another aspect of Latinx culture and heritage.

Multicultural Club strives to raise awareness and increase appreciation for Hispanic culture and history within the Harker community. Multicultural Club Co-President Melody Luo (12), who identifies as Asian American, encourages students to embrace the different cultures around them through education, starting with articles, books and immersion into these cultures.

“It’s really important for us to be open-minded to others who may not be of the same ethnicity or race as us,” Melody said. “By being open to listening to other people’s problems when it comes to their difficulty of being a specific race or heritage, then we can be a more embracing student community.”

Although Joanna appreciates the school’s efforts to educate its members about Latinx culture, she believes that increasing the Latinx population at Harker would be the more effective way to build an accepting, welcoming community

“I feel like there isn’t a lot of [the] Latinx community at Harker, so it’s very easy for the culture to get lost,” Joanna said. “I absolutely love the idea of other people learning about the culture, but ultimately it’s hard to connect with people that have the same experiences growing up [as you].”

California history’s deep roots in Hispanic and Latinx culture

To celebrate the culture and contributions of the Hispanic population, then-president Ronald Reagan established National Hispanic Heritage Month on August 17, 1988. The month-long celebration commenced on the fifteenth of September, which marks the independence day for Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua, and ended on Oct. 15. Mexico and Chile commemorate their independence days on Sept. 16 and Sept. 18, respectively.

“It’s an opportunity to do a spotlight on a culture and have a little bit more inclusivity,” Aguero-Esparza said, about the national holiday. “Wherever you are, in terms of the workplace or school, the value of these celebrations or focal points or spotlight is to create more visibility in recognizing cultures that are not as highlighted or not as mainstream.”

The territory of California itself resided under Mexican rule until 1848, when Mexico surrendered California to the U.S. in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican-American War. Almost 200 years later, the effects of Spanish ownership remain through prominent displays of Hispanic culture throughout the state. For instance, the Mexican Heritage Plaza, a center located in San Jose, organizes dance performances, music shows and cultural festivities. Restaurants such as Luna Mexican Kitchen, La Victoria and Mezcal draw crowds of various ethnicities through their doors to experience their wide variety of authentic dishes.

Throughout California history, notable Hispanic figures have left lasting legacies. Born in the Mayfield neighborhood of San Jose, César Chávez worked as a labor leader and civil rights activist who championed the rights of migrant workers. In honor of his work, Chávez received a town square dedicated to him titled “Plaza de César Chávez” in Downtown San Jose. Additionally, San Jose State University commemorates his achievements through the Arch of Dignity, Equality and Justice.

Since the 1980s, the Hispanic population in California has more than doubled, and currently 15.6 million people, or one in four individuals, identify as Latinx in California. In 2015, the Office of Historical Preservation published a history project titled “Latinos in the Twentieth Century California,” which highlights the influences, contributions and history of the Latinx community in California.

Hispanic culture pulses all over campus—in the lunchrooms, in the Spanish classrooms, in California. Latinx students and faculty engage with their culture through family gatherings, immersing themselves in Hispanic foods, and creating art that highlights their roots: Latinx students and faculty, though they remain under 2% of the school population, creates a rich culture, not only during National Hispanic Heritage Month and La Noche Cultural but all year round, in and outside of classes. “Let’s head over to Manzanita!” contains the history from which those lush manzana apples came, the stories that the Latinx community tells currently and the Hispanic food in the lunchrooms today—these parts of the school that makes up a shared identity.

“It’s important to recognize the contributions of minorities,” Tejada said. “Their presence here adds color and beauty to this country. It adds to the diversity of this country, and I think that’s beautiful. It’s not just about the language: it’s about the culture, and all we bring to this country.”