‘It burns and it burns and it burns’: California wildfires raze 2.4 million acres in midst of climate emergency, community members recover and reflect

October 10, 2021

“It was like driving into hell.”

A pitch black sky surrounded upper school Spanish teacher Diana Moss as she neared the Dixie fire, while she passed through the small city of Red Bluff in Tehama County. Dark smoke loomed over her car, and she felt her eyes burn and throat close. In the distance, she saw the beginning of the blaze, a “faint glow” stark against a dark sky. She was on a trip to visit family and friends and to explore a sustainable residential development in Late August. She had left San Jose and was on her way to Salem, Oregon, when she found herself forced to drive past the fire, an experience she would never forget.

Moss had driven through the largest fire of the year, the Dixie Fire, which is located in Butte, Lassen, Plumas, Shasta and Tehama counties and originated in mid July. Since then, the fire has spread across 963,309 acres, and is 94% contained at the moment. The Dixie Fire is now the largest single-source fire in California history. In addition to the Dixie Fire, there have been 7,768 other wildfires this year. In total, these wildfires have devastated over 2.4 million acres and damaged 3,050 structures. Some other major active fires are the Monument Fire in Trinity County, which has burned 223,001 acres and is 81% percent contained, and the Caldor Fire in El Dorado County, which has burned 221,775 acres and is 93% contained.

2020 wildfires prompted evacuations: One year later, community members reflect on the aftermath

On Sept. 9, 2020, about a year ago, wildfire smoke tinted the sky above the Bay Area orange, and in the days following, air quality continuously worsened as ash fell from the clouds. In 2020 alone, 5,716 fires burned 279,885 acres as thousands of residents evacuated. One of the largest of these fires took place within the CZU Lightning Complex, which is spread between Santa Cruz and San Mateo counties, and it burned 86,509 acres and destroyed 1,490 structures. The fire was contained in about a month.

Upper school computer science department chair Dr. Eric Nelson lives in the heart of the CZU Lightning Complex, an 86,000 acre region which nearly burned to the ground last fall after being struck by thousands of lightning bolts during a severe thunderstorm. The risk of nearby fire forced him, his wife and his mother-in-law to evacuate their home for multiple weeks, but their neighborhood and house narrowly survived.

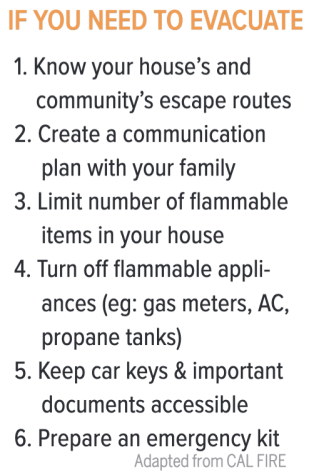

“We had an evacuation plan, and it worked,” Dr. Nelson said. “We got out of the house in two hours. You could see the individual trees going up in flames. Fortunately, we didn’t lose the house, but they got very close. Still, every time you walk outside you get ash dust kicking up under your feet.”

Dr. Nelson and his family ended up staying at his daughter’s home as they waited for fires to die down. He appreciates the generosity and hospitality offered by various community members to those who evacuated.

“I found the community extraordinarily supportive because we suddenly found ourselves at 11 o’clock at night on the 18th of September — we had to leave, and fortunately, we had a place to go,” he said. “I had multiple offers of places to stay, including coming from [head of school Brian] Yager. There was no shortage of support, both financial support and food service, being offered for the faculty have been displaced, which was very helpful.”

Last year, over 100,000 California residents evacuated, including Harker community members. In the midst of the wildfire season, Yager sent out an email, saying that the school would be “sensitive to the needs of our students who may have relocated” and that counselors would be available to help.

Essential fire: How do wildfires play key ecological roles?

Most wildfires begin from mishaps at campsites, electrical fires and lightning strikes. In lightning strikes such as those at the CZU Lightning Complex, air molecules moving past each other generate friction that can cause a static electrical charge. That charge moves between the ground and the air, releasing enough energy to generate heat to start a flame. In the past, the Pacific Gas and Electricity Company (PG&E) intentionally issued power outages in at-risk areas to lower the possibility of starting a fire.

According to biology and environmental science teacher Jeff Sutton, when humans are removed from the equation, these natural fires can reinvigorate ecosystems, add nutrients to the soil and limit dominant species. For conifers like redwoods, fires can help to release or germinate the seeds. More species within the climax community—an ecological community in which populations remain stable—can grow after a low fire, which stays near the ground. Prairies also depend on fires to restore balance.

“Prairie fires are really important because woody species like trees and shrubs will take over the prairie unless you have periodic fires that burn from lightning,” Sutton said. “They will burn the grass, but the grass roots are protected. Once the fire has gone through and it rains, you get more nutrients put back into the soil, and the grass regrows.”

For thousands of years, indigenous peoples mirrored this pattern of burning and regrowth to reap benefits such as nutrients and biodiversity through prescribed fires. After this process, the newly burned land is replenished with nutrients that allow more plants to thrive.

“Indigenous populations have been setting what we call prescribed fires, meaning they know the land: they’re deeply connected to the land and its well-being and its sustenance,” upper school biology teacher Eric Johnson said. “They would prescribe fires and burn this small area of land so that it can regenerate, so that it can grow new crops that can bring in new biodiversity.”

For the Yurok Tribe in Northern California, prescribed burns ensured more fauna to hunt and flora such as acorns as well as fewer invasive species. Plants like California hazel grow straighter after fires, making them more preferable for weaving baskets. Controlled burns also prevented large fires from destroying villages and cleared trails for walking.

In contrast to Native Americans’ positive mindset toward fire, in the early 1900s, forest management considered fires detrimental and put out any fires they observed. Rather than preventing damage, these actions allowed forest litter to accumulate, creating more fuel for a potential blaze.

This fuel leads to damaging crown fires, which spread to many trees through the canopy. Since more people populate the forests now, forest management and residents extinguish fires before they expand. Although this habit may protect human lives and properties, it limits growth of other species and actually results in devastatingly large and harder-to-control fires.

“When fires are put out by humans and the debris is allowed to build up in the forest or in the prairie, fires tend to burn hotter and faster, and they can destroy some of the species that are typically going to stick around in the ecosystem under normal ecological conditions,” Sutton said.

Regions that have not been burnt in long periods of time and that have large amounts of forest litter are the most susceptible to wildfires. These have become increasingly common in California.

“Now we have big areas of land, [where even] a single spark can take out all the land. It burns and it burns and it burns,” Johnson said.

Organizations have taken action to target this problem, including the Goat Girls LLC. Based in San Luis Obispo County and founded in 2018, the Goat Girls LLC provides grazing services to clear out vegetation, reducing the amount of fire fuel as well as clearing invasive species. Animals remove mass of fine fuel (flammable dry grasses with small diameter) and reduce the height of vegetation. These changes to the landscape cause flame heights to be smaller, making them less intense and less likely to rise into tree canopies. Grazing in particular has unique advantages that make it versatile and less invasive than herbicides.

“The nice thing about grazing, whether it’s cattle, sheep, goats, or horses, is that they’re natural,” Goat Girls LLC founder Beth Reynolds said. “Particularly, sheep and goats are very good at getting into hard-to-reach places. We do a lot of steep canyons and a lot of steep mountain sides where machinery isn’t viable and it’s too close to homes to do a controlled burn.”

Vulnerable populations adapt and take protective precautions

Members of the Harker community living in regions with high volumes of vegetation cleaned their homes in preparation for the wildfire season. Avery Olson (11), who lives in the Santa Cruz mountains, right outside of Scotts Valley, has taken extra precautions to protect herself and her family this year after they considered evacuating last fall.

Members of the Harker community living in regions with high volumes of vegetation cleaned their homes in preparation for the wildfire season. Avery Olson (11), who lives in the Santa Cruz mountains, right outside of Scotts Valley, has taken extra precautions to protect herself and her family this year after they considered evacuating last fall.

“My dad around our house has been cleaning out extra weeds and stuff that could easily burn, and we want to be conscious about how bad the drought is this year, especially since there’s no water in the reservoirs,” Avery said. “[I wish people would be] more conscious about water usage and the drought.”

Although this year there are no major active fires near the Harker School, wildfires can pose serious health issues as smoke affects the respiratory system. During the pandemic, public spaces with clean air may be difficult to find. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that households use portable air cleaners indoors, frequently turn on air conditioning and fans and avoid activities that increase pollution. Individuals with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and heart disease as well as pregnant women and children are most susceptible to having severe symptoms in response to wildfire smoke exposure.

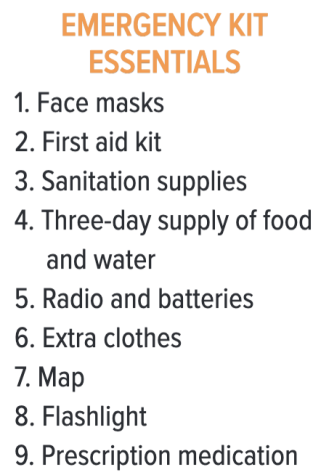

“If the air quality is at a certain point where it can be dangerous to be outside, we would recommend moving all activities indoors. If you have to be outside, we would recommend a mask, particularly a N95 mask, that would help to block those particles that could be inhaled during a wildfire,” upper school nurse Jennifer Olson said.

As a result of dangerously high air quality, administration cancelled junior and senior class trips, which were planned for Aug. 18 and 19. Additionally, after school sport practices have been cancelled or moved indoors on days with severe smoke. Some symptoms from inhaling excessive wildfire smoke resemble those of COVID-19, including coughing, sore throat and difficulty breathing.

Besides physical dangers, the wildfires may affect peoples’ mental health. California residents could frequently worry about the safety of friends and family. In addition, social media, which is constantly reminding users about climate change and spreading updates about fires, further harms younger generations.

Climate change exacerbates dangers of wildfires

Laurie Jin (11), a research officer at the climate change organization Change The End, knows that many people in the community have been personally affected by the wildfires. She hopes California residents will collaborate to diminish the danger they pose to local ecosystems and environments.

“A lot of people don’t see the impact of climate change since they’re far away, but as Californians who have been here and who have actually smelled burning [material] coming from forests around us, we take it more personally,” Laurie said. “I know some people think that it’s hard to make a great impact by yourself, but if we build a community, it will be a lot easier to do it together.”

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), California’s average temperature in June reached 75.1 degrees Fahrenheit, 6.8 degrees higher than the average temperature from 1901 to 2000. July’s average temperature of 80.0 degrees was 5.3 degrees higher than average. On July 9, Death Valley set a new record for the hottest temperature measured in history after reaching 130.0 degrees.

Evidence shows that climate change has severely increased the number of acres burned by wildfires every year. This occurs because the warm air has a low atmospheric vapor pressure deficit (VPD), so the air cannot hold much water. Climate change has worsened over recent years: 2020’s average temperature was 1.76 degrees Fahrenheit higher than the average of the 20th century, and the earth becomes 0.14 degrees warmer every decade. As a result, this year’s wildfire season may be extremely devastating.

“[California’s] vegetation loses its moisture and burns easily, and strong winds facilitate the spread of the flames,” Camilla Lindh (12), co-president of Green Team, said. “This makes California especially susceptible to wildfires since we have such dry heat, and we don’t have that much humidity. With climate change, which makes the weather warmer, there are more wildfires.”

California has committed to reducing the vegetation on a half-million acres under the California Vegetation Treatment Program (CalVTP), a program certified by the California Board of Forestry to lower wildfire risk. Besides reduction, vegetation treatments also include fuel breaks (strips of vegetation altered to stop or slow down a fire) and restoration of “ecological processes, conditions, and resiliency to more closely reflect historic vegetative composition, structure, and habitat values.”

In addition to CalVTP’s, other initiatives study methods to reduce wildfire dangers, with researchers now investigating traditional fire management practices used by local indigenous tribes. A Stanford-led study featuring the Yurok and Karuk tribes found that along with reducing wildfire risks, traditional fire suppression techniques reinvigorate the tribes’ cultures and economies. According to the researchers, Native American burning techniques could be integrated into current fuel reduction plans to meet cultural needs by, for example, including hazelnut shrub and pile burning in forest management protocols.

In their own contribution to combatting large wildfires, Green Team plans on re-opening their Forest Management section, which spreads information about and promotes bills that help out forests to the school community.

“As individuals, we really want to focus on saving water because we do have a drought, and we really could use that water to contain wildfires and to be able to bring moisture back to vegetation,” Camilla said.

Moss describes wildfires as “a new reality” that “has implications for all of us.” As club adviser of Green Team, she encourages discussions about climate change and urges the youth to take action in demanding sustainability, even at the small scale of doing so at home.

“The crisis is here. It is going to be impacting you probably more than me, and we really need to get our youth activated and energized to be demanding that we transition to a sustainable energy supply,” she said.

Additional reporting by Emily Tan, Arjun Barrett and Mark Hu.