Hard Hits: Concussions on the Rise

January 8, 2017

“I got kneed to the head. The opponent was coming for me and he jumped as I was going for the tackle. It didn’t go as I planned and it came straight to my head… At first I got up and I felt perfectly fine, and then I was like ‘Whoa,’ and I felt [like] I was [not] even inside my own mind or body anymore. When I fell to the ground, my team and coach came running for me,” Norman Garcia (12) said, recalling the third Harker football game of last year. “I’ve had three concussions. The last one I had was pretty bad.”

A concussion is a mild traumatic brain injury that is caused by a sudden blow to the head or a hit to the body that results in the brain rapidly accelerating and decelerating within the skull. This movement of the brain injures the cerebral cells and creates biochemical changes that make it difficult for the brain to function normally. These changes occur within the minutes and hours after the impact and lead to a multitude of neurological symptoms that can persist for weeks or longer. Individuals with such injuries may often note temporary loss of consciousness, memory problems, dizziness, headaches, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and sleep disturbances.

Norman’s symptoms lasted for nearly two months, during which time, he was out of both school and sports.

“I was lying miserably in bed. I was very sensitive to light and noise,” he said. “I couldn’t even look at my phone.”

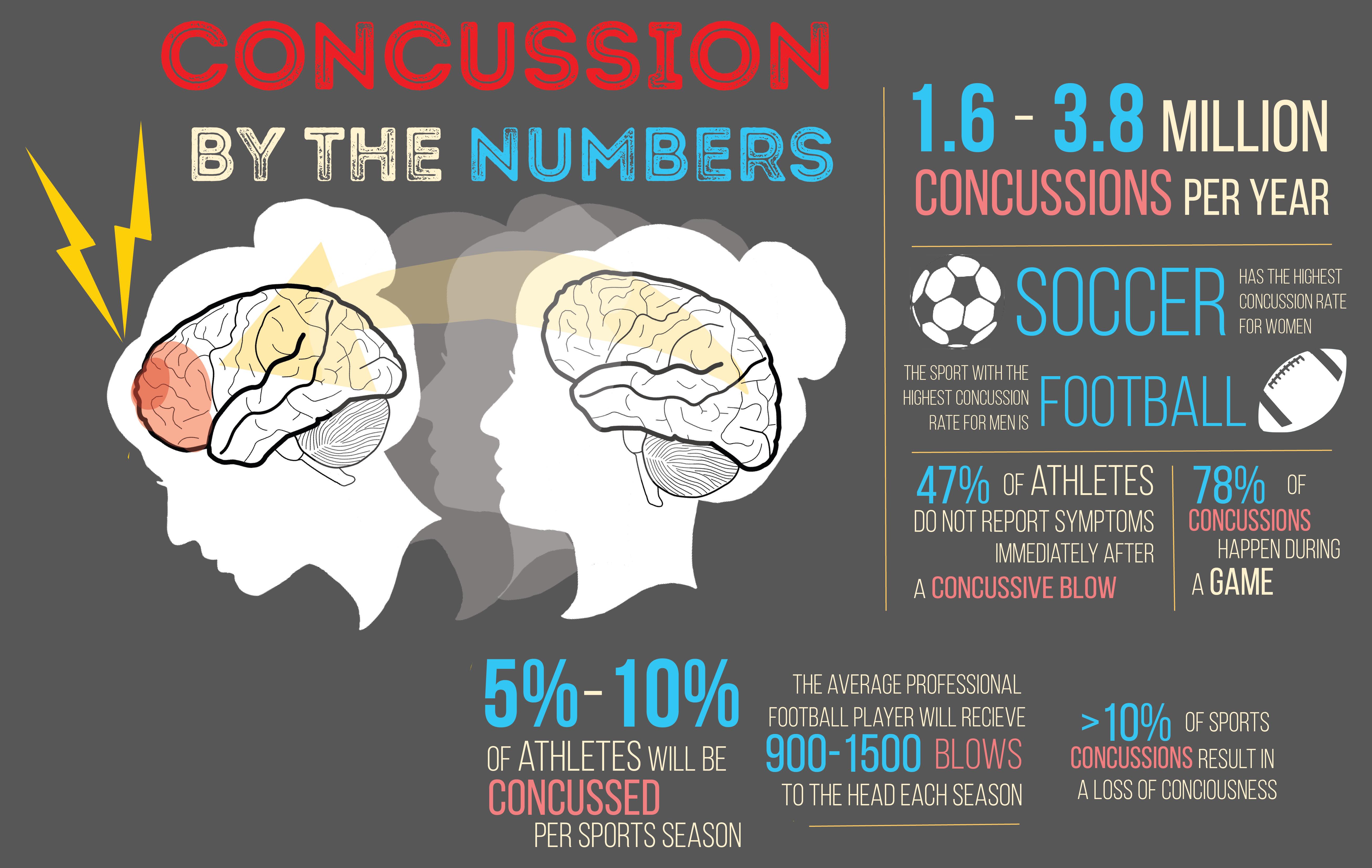

Norman’s situation is not a trivial problem. According to the CDC in 2010, there were about 2.5 million emergency department visits associated with traumatic brain injuries. About 10 percent of these injuries are concussions in individuals less than 19 years old and related to sports and recreation. A recent report by CNN notes that these numbers continue to rise. Not only does it seem like the condition is under diagnosed, but according to former NFL player and now Stanford Health Care physician, Dr. Russell Stewart, the increased incidence is “likely multifactorial and partially attributable to the increasing size and speed of players and the subsequent higher energy collisions, along with improved rates of diagnosis and increased social awareness and media attention.”

Despite being such a major problem in this age group, concussion protection rules only began to emerge in the late-2000s. In October 2006, 13-year-old Zackery Lystedt collapsed from a brain injury when he returned to a middle school football game just minutes after sustaining a concussion. He spent the next three months in a coma and took nearly three years, after intense rehabilitation, before he could even stand with assistance. In May 2009, Washington State passed the Zackery Lystedt Law and became the first state in the country to mandate a comprehensive youth concussion state law. It wasn’t until January 2014 when Mississippi signed a similar law into action, that all 50 states had a concussion law in place.

These state laws provided for the creation of guidelines and education for schools, coaches, parents, and athletes. The California Interscholastic Federation (CIF) is the state’s governing body tasked with creating and implementing these guidelines for all high school and middle school sports. The organization mandates that not only must all coaches receive training on concussion treatment, but a head injury or concussion information sheet must be signed annually by both the athlete and a parent or guardian prior to participation in any sport.

More importantly, these laws allowed for the immediate removal of a player if a concussion is suspected and required written consent for a player to return to play by a licensed health care provider who has specific training in the management of concussions. However, any such guidelines are complicated to put into place due to having multiple stakeholders and varying interpretation of how these rules should be carried out.

The CIF rules definitely help to prevent athletes from getting injured, but when a head injury does occur, these individuals are typically taken to a medical center or local ER for evaluation. Interestingly, even though concussions are so prevalent in our medical system, it is still a diagnosis based only upon a physician’s examination of the patient as all objective tests, such as CT scans and lab work, are normal.

According to Dr. Tina Tsou, Coordinator of Neuropsychological Services at El Camino Hospital, physicians look for “signs such as delayed verbal responses to questions, confusion, balance problems, irritability, and memory deficits.” Suspicions of concussion are typically confirmed by neuropsychological testing and repeat neurological examinations over a period of weeks and months.

As Director of the NBA’s concussion program and the team physician for the United States at the 2014 Olympic Winter Games, Dr. Jeffrey Kutcher feels that the some of the biggest issues center on awareness that an individual even has an injury and then understanding an individual’s deviation from the baseline. He has been instrumental in developing protocols for education and evaluation.

“It’s incumbent on team physicians, trainers, and coaches to make sure that their athletes are informed and that everyone is observing for signs and symptoms of head injuries,” he said. “The competitive spirit within sports can lead to under-reporting and neglect of injuries.”

What worries both families and coaches is what to do next. Questions around monitoring, treatment, returning to school or work and when an individual can be cleared for sports are not always easy to answer. UCLA senior athletic director Tandi Hawkey describes the intensive monitoring protocol for her players including a daily evaluation that involves the self-reporting of symptoms and objective neurocognitive testing that assesses memory, processing, and balance. She notes that the initial focus is to remove all external physical and cognitive stresses such as phones, computers, and video games. As symptoms normalize to baseline, the athlete is exposed to gradually increasing levels of physical activity eventually leading back to contact training and full competition.

The main concern is that players could get cleared to play too quickly, putting them at risk for a condition known as Secondary Impact Syndrome, which involves a second insult to the head following an initial concussion, sometimes weeks later. The first concussion leads to an alteration of the cerebral metabolism and the second blow causes the healing brain to lose its ability to control and regulate its internal blood flow. This rare, but devastating process, can lead to diffuse cerebral edema, brain herniation and even death.

“You can only get second impact syndrome if you go back too soon while symptomatic,” Dr. Holly Benjamin, Director of Primary Care Sports Medicine at the University of Chicago said. “Any athlete who has any signs of lingering concussion symptoms or any difference from baseline should not be cleared to return to play.“

However, this is easier said than done. Hawkey notes that “coaches often want to push athletes to be tough and play through pain, but head injury symptoms should not be ignored.”

Students also feel the guilt of disappointing their team members. Swimmer Kate Chow (11), who had a concussion during a match last summer, acknowledged that “being taken out of a sport is quite hard because you see your team doing all the work, and emotionally, you feel like you need to help.”

Kate Chow (11) performs a backflip into the depths of the swimming pool. The team placed first at the Union Americana de Natación (UANA) Pan American Synchronized Swimming Championship in Puerto Rico from Sept. 1 to 4, 2016.

“We understand the risks of trauma and what return to play means in sports better than other specialists often do,” Dr. Benjamin said, asserting that clearing players for a return to sports requires providers who are trained in assessing and treating.

While California’s first youth sports concussion safety law was signed in October of 2011, it wasn’t until January 1, 2015 when an amended law, AB 2127, placed limits on full-contact practices and mandated graduated return-to-play protocols of no less than seven days. Prevention and precaution are beginning to take an active role in concussion management.

Even with the tremendous amount of recent education and awareness campaigns around concussion, Dr. Stewart feels there is so much more to learn about head injuries in sports.

“The NFL in particular has strict policies for evaluating, monitoring and clearing players with head injuries,” he said. “They are also trying to make rule changes to limit helmet to helmet hits and shots on defenseless players.”

However, the impact of such alterations in policy and play need to be measured and understood. The NFL has a vested interest in understanding this injury process given the intense scrutiny the organization has faced over the last several years involving chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a progressive degenerative disease from repeated head trauma, found in the brains of former players.

Dr. Benjamin is working to answer such questions by leading a national study on concussions involving 25,000 National College Athletic Association (NCAA) student athletes and 30 major hospital centers. This longitudinal three year multi-center trial will follow the natural history of concussions from a comprehensive preseason baseline evaluation to monitoring after a head injury. The research will give an unprecedented view into this disease process and allow physicians to better understand both short and long-term evolution of head injuries and the effect on these players.

Other researchers, such as Stanford University’s Dr. David Camarillo, are approaching their research from a different angle by focusing on the biomechanical effects of concussion through the use of sensors built into the helmets and mouthguards of football players. By understanding the force and direction of the impact involved in a head injury and by following clinical data through radiological images and blood testing, Dr. Camarillo’s lab hopes to eventually develop athletic equipment that will prevent the concussion from occurring in the first place. Until that happens, all individuals at risk for concussion need to continue to be proactive.

Experts feel that most concussions will heal given enough time. But significant and repeated injuries may not allow that to happen. Norman Garcia knows this first hand. “My memory hasn’t been as strong as it usually has been before that,” he said. “My memory has deteriorated a little bit and I still have headaches too.”

Additional Reporting by Julia Amick

This piece was originally published in the pages of Wingspan on December 14, 2016.