High school curricula reveal startlingly low levels of Holocaust education

December 3, 2021

International Holocaust Remembrance Day occurs every year on Jan. 27 and marks the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising as a memorialization of the six million Jews murdered during the Holocaust.

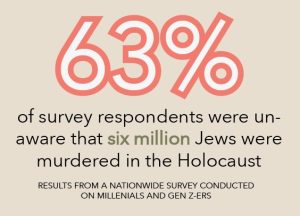

Despite the impact of the Holocaust on the history and culture of Jewish populations and future generations, education about the Holocaust is startlingly low. In a survey conducted nationwide on millennials and Gen Z-ers, 49% “have seen Holocaust denial or distortion posts on social media or elsewhere online,” while 63% of all respondents do not know that six million Jews were murdered. Additionally, only 56% could identify the camp Auschwitz-Birkenau, while 48% were unable to identify a single camp out of the 40,000 camps across Europe. A shocking 11% even believe that Jews caused the Holocaust.

“That’s an insanely high number, a scarily high number, and what that says is that there are schools in the country that either don’t cover it at all or it’s too small of a unit and it’s not sinking in,” Literature of the Holocaust teacher Ohad Paran said. “To me, the Holocaust is a vehicle that we can use to discuss extremism because it’s so bizarre and so organized. An entire country was structured to do this thing, so how do we as members of society prevent that from occurring again?”

Dr. Amy Simon, a William and Audrey Farber Family Endowed Chair in Holocaust studies and European history professor at Michigan State University, acknowledges advancements in Holocaust education in recent years, such as the Never Again Education Act, or H.R.943, passed in 2020. However, she believes that the topic is often taught in a “watered down” way.

“How do you teach about the Holocaust to younger kids? Because obviously, you shouldn’t get into the really gory details of murder, but then, a false narrative of what the Holocaust really was all about can be spread,” Simon said. “For example, a lot of schools teach ‘The Boy in the Striped Pajamas.’ It’s terrible. It sends a horrible message about the Holocaust. It doesn’t teach anybody about anything.”

Despite the overall lack of emphasis in the current American education system, the Holocaust still haunts those whose families experienced its horrors.

“Sometimes, late at night, I’m up thinking about these things or I’m having a nightmare because this is what happened,” Julia Yusupov (’21) said. “The fact that there are people in this world that say it didn’t happen or this doesn’t exist really doesn’t sit well with me. It definitely impacts my life every day.”

Yusupov, who identifies ethnically as Jewish and whose grandparents are Holocaust survivors, is currently pursuing the Manovill Holocaust History Fellowship at the Jewish Family and Children’s Services Holocaust Center after learning of her family’s history through her grandparents’ stories.

“It’s not ingrained into our school system to educate people about the Holocaust. In a perfect world, Holocaust education and all genocide education would be brought to every single person on the planet. It’s just not the case,” Yusupov said. “I really hope it does come to a point because it’ll actually make the phrases ‘never forget’ and ‘never again’ manifest properly.”

The Harker upper school has taken measured steps to implement the history of the Holocaust into its upper school curriculum. Courses that cover the Holocaust include the World History classes and the AP European history class, course paths required for all upper school students in their sophomore year.

Upperclassmen have the option to take the History of the Holocaust and Genocide elective and the Literature of the Holocaust elective, and the topic is also covered in upper school history teacher Mark Janda’s Social Justice course, which was introduced last year.

“We’re talking about civic engagement, we’re talking about how regular people can be fully engaged in the community around them in order to create greater justice for all of our peers, and part of that means being on the lookout for the kinds of behaviors, government behaviors and community behaviors that lead to things like the Holocaust,” Janda said. “So to me, it’s embedded within the very meaning of social justice.”

Furthermore, the Student Diversity Coalition (SDC) worked with Paran and Yusupov to invite Holocaust survivor Leon, who is currently a member of the JFCS Holocaust Center’s William J. Lowenberg Speakers Bureau, to speak with the upper school this past April. Leon, who was born in Czernowitz, Romania, in 1931, was only 10 years old when the Nazis invaded.

After being forced to leave his hometown in Sept. 1941, he and his family were sent to the Mogilev-Podolsk Camp, which they successfully escaped from. They stayed in the Djurin Ghetto for two years until the ghetto was liberated in March 1944.

“There were only 18 apartment building[s], 14 were previously occupied by Jewish families,” Leon said of returning to his apartment complex in his hometown. “We were the only ones to return.”

JFCS Holocaust Center Education and Marketing Manager Penny, who helped host the speaker event, emphasized the importance of educating today’s youth about the Holocaust and the events leading up to it.

“One thing we always emphasize is that the Holocaust did not happen overnight,” Penny said. “That’s incredibly important for people to understand. Because if you don’t have a full understanding of how genocide occurs, then I don’t think you really will have a full understanding of how to stop it from happening.”

Despite Harker’s efforts to incorporate the Holocaust into its curriculum, Janda believes there can be more done to decrease its opacity and expand the school’s scope of education.

“We can have school announcements about International Holocaust Remembrance Day,” Janda said. “In any variety of other heritage months and memorials, we can do a better job of balancing those things, making them part of assemblies and school meetings, because there’s always more we can do.”

Janda believes that education on the Holocaust helps students not only to understand the gravity of its history but also to apply the patterns to other modern genocides ongoing in the world since governments that “scapegoat” select communities continue to exist. Janda mentions the 21st-century Rwandan genocide, the Balkan states genocide and the Uyghur concentration camps in China as a few modern-day examples.

“The Holocaust was an industrialized, mechanized effort to wipe out an entire population, and we’ve only achieved greater and greater means to do the same thing again in the generations since,” Janda said. “We have to keep learning about it in order to make sure we’re informed so we can stand up when we see it happening. We actually have to remind all of us how [the Holocaust] came to be in the 1930s of Germany to prevent it from happening again.”

Additional reporting by Lucy Ge.