Pulse of the People: ‘Never forget, never again’

December 3, 2021

Harker Aquila spoke with upper school faculty and students, local Jewish synagogue members and Holocaust research experts on the lasting impacts of the Holocaust and the value and necessity of integrating its historical significance into today’s conversations.

In conversation with upper school Literature of the Holocaust teacher, Holocaust survivor’s grandson

“To forget would be not only dangerous but offensive; to forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time.”

These words, penned by Holocaust survivor and author Elie Wiesel, are a part of his internationally acclaimed memoir “Night,” one of the texts studied in upper school English teacher Ohad Paran’s Literature of the Holocaust semester elective class.

According to Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Holocaust survivors continue to experience varying degrees of difficulty on a day-to-day basis, with each survivor reacting to life postwar in a different manner.

But long before he even began teaching the depths and nuances of what history brands as the Holocaust, Paran spent his childhood years with a grandfather who he did not know was a Holocaust survivor until the age of 11. Though Paran spent days in school learning the historical facts of the Holocaust — such as the dates of each battle and camp liberation — he only began to connect his grandfather to the storyline when he put into perspective his grandfather’s age during World War II.

Paran’s grandfather spent the majority of his twenties in three of the “worst and most notorious” Nazi concentration camps: Treblinka, Auschwitz and Dachau.

“He survived all of that, and he built an incredible life for himself and my grandmother and my father in Israel after that,” Paran said. “But only when I asked him did he tell me that he was [in the camps] since he never really shared the details until very, very late in his life.”

Paran’s grandfather only received up to a fifth-grade education, but in his later life he helped found the Israeli National Health System, a project he started working on when he was 19.

“I always wanted to do the [Literature of the Holocaust] class to honor his memory,” Paran said. “He exited the Holocaust with what seemed to be no PTSD, no anger, no animosity towards people. I found the story that he told of from when he was born, to what happened to him during the Holocaust, to the life that he ended up building in Israel to be so incredible.”

From this first survivor story, Paran began reading the stories of others, determined to connect the past with the present, the timeline of his grandfather with his own.

“The common thread I found was that before the Holocaust, [survivors] were completely ordinary people who were not special in any way,” Paran said. “Yet, somehow, they were thrown into these circumstances that were totally insane, they found a way to survive in the face of atrocities that are hard to wrap your head around and most of them came out of that and were able to build a life of relative success. That, to me, is unbelievable.”

According to Paran, the human ability to internalize varying methods of coping with PTSD and trauma is a nuanced and heavy subject, but through his class and its texts, he hopes his students can begin to understand the Holocaust’s effects on the mental health of survivors after the war.

“That silence also led to a lot of people not being able to be as successful as they could have been if there had been a culture of openness around trauma and mental health,” Paran said, referring to a subject he highlighted during a class period. “Over the years, my class has evolved a little bit — to not only talk about the concrete events of the Holocaust but also to look at the mental health aspect that the authors explore and to talk about how we cope with any kind of trauma that we have in our lives.”

High school curricula reveal startlingly low levels of Holocaust education

International Holocaust Remembrance Day occurs every year on Jan. 27 and marks the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising as a memorialization of the six million Jews murdered during the Holocaust.

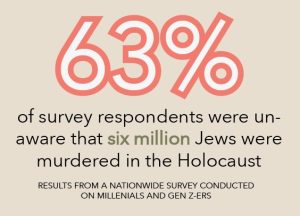

Despite the impact of the Holocaust on the history and culture of Jewish populations and future generations, education about the Holocaust is startlingly low. In a survey conducted nationwide on millennials and Gen Z-ers, 49% “have seen Holocaust denial or distortion posts on social media or elsewhere online,” while 63% of all respondents do not know that six million Jews were murdered. Additionally, only 56% could identify the camp Auschwitz-Birkenau, while 48% were unable to identify a single camp out of the 40,000 camps across Europe. A shocking 11% even believe that Jews caused the Holocaust.

“That’s an insanely high number, a scarily high number, and what that says is that there are schools in the country that either don’t cover it at all or it’s too small of a unit and it’s not sinking in,” Literature of the Holocaust teacher Ohad Paran said. “To me, the Holocaust is a vehicle that we can use to discuss extremism because it’s so bizarre and so organized. An entire country was structured to do this thing, so how do we as members of society prevent that from occurring again?”

Dr. Amy Simon, a William and Audrey Farber Family Endowed Chair in Holocaust studies and European history professor at Michigan State University, acknowledges advancements in Holocaust education in recent years, such as the Never Again Education Act, or H.R.943, passed in 2020. However, she believes that the topic is often taught in a “watered down” way.

“How do you teach about the Holocaust to younger kids? Because obviously, you shouldn’t get into the really gory details of murder, but then, a false narrative of what the Holocaust really was all about can be spread,” Simon said. “For example, a lot of schools teach ‘The Boy in the Striped Pajamas.’ It’s terrible. It sends a horrible message about the Holocaust. It doesn’t teach anybody about anything.”

Despite the overall lack of emphasis in the current American education system, the Holocaust still haunts those whose families experienced its horrors.

“Sometimes, late at night, I’m up thinking about these things or I’m having a nightmare because this is what happened,” Julia Yusupov (’21) said. “The fact that there are people in this world that say it didn’t happen or this doesn’t exist really doesn’t sit well with me. It definitely impacts my life every day.”

Yusupov, who identifies ethnically as Jewish and whose grandparents are Holocaust survivors, is currently pursuing the Manovill Holocaust History Fellowship at the Jewish Family and Children’s Services Holocaust Center after learning of her family’s history through her grandparents’ stories.

“It’s not ingrained into our school system to educate people about the Holocaust. In a perfect world, Holocaust education and all genocide education would be brought to every single person on the planet. It’s just not the case,” Yusupov said. “I really hope it does come to a point because it’ll actually make the phrases ‘never forget’ and ‘never again’ manifest properly.”

The Harker upper school has taken measured steps to implement the history of the Holocaust into its upper school curriculum. Courses that cover the Holocaust include the World History classes and the AP European history class, course paths required for all upper school students in their sophomore year.

Upperclassmen have the option to take the History of the Holocaust and Genocide elective and the Literature of the Holocaust elective, and the topic is also covered in upper school history teacher Mark Janda’s Social Justice course, which was introduced last year.

“We’re talking about civic engagement, we’re talking about how regular people can be fully engaged in the community around them in order to create greater justice for all of our peers, and part of that means being on the lookout for the kinds of behaviors, government behaviors and community behaviors that lead to things like the Holocaust,” Janda said. “So to me, it’s embedded within the very meaning of social justice.”

Furthermore, the Student Diversity Coalition (SDC) worked with Paran and Yusupov to invite Holocaust survivor Leon, who is currently a member of the JFCS Holocaust Center’s William J. Lowenberg Speakers Bureau, to speak with the upper school this past April. Leon, who was born in Czernowitz, Romania, in 1931, was only 10 years old when the Nazis invaded.

After being forced to leave his hometown in Sept. 1941, he and his family were sent to the Mogilev-Podolsk Camp, which they successfully escaped from. They stayed in the Djurin Ghetto for two years until the ghetto was liberated in March 1944.

“There were only 18 apartment building[s], 14 were previously occupied by Jewish families,” Leon said of returning to his apartment complex in his hometown. “We were the only ones to return.”

JFCS Holocaust Center Education and Marketing Manager Penny, who helped host the speaker event, emphasized the importance of educating today’s youth about the Holocaust and the events leading up to it.

“One thing we always emphasize is that the Holocaust did not happen overnight,” Penny said. “That’s incredibly important for people to understand. Because if you don’t have a full understanding of how genocide occurs, then I don’t think you really will have a full understanding of how to stop it from happening.”

Despite Harker’s efforts to incorporate the Holocaust into its curriculum, Janda believes there can be more done to decrease its opacity and expand the school’s scope of education.

“We can have school announcements about International Holocaust Remembrance Day,” Janda said. “In any variety of other heritage months and memorials, we can do a better job of balancing those things, making them part of assemblies and school meetings, because there’s always more we can do.”

Janda believes that education on the Holocaust helps students not only to understand the gravity of its history but also to apply the patterns to other modern genocides ongoing in the world since governments that “scapegoat” select communities continue to exist. Janda mentions the 21st-century Rwandan genocide, the Balkan states genocide and the Uyghur concentration camps in China as a few modern-day examples.

“The Holocaust was an industrialized, mechanized effort to wipe out an entire population, and we’ve only achieved greater and greater means to do the same thing again in the generations since,” Janda said. “We have to keep learning about it in order to make sure we’re informed so we can stand up when we see it happening. We actually have to remind all of us how [the Holocaust] came to be in the 1930s of Germany to prevent it from happening again.”

Additional reporting by Lucy Ge.

Jewish community members urge alliance to battle antisemitism

“No one is born with hate,” said Michelle Dorfman (11), whose great-grandfather passed away in the Holocaust. “It’s something that you’re taught. So the more we become educated about a topic, the [smaller] the possibility of having prejudice against that.”

Since 1979, the United States experienced the highest number of antisemitic incidents in 2019, with more than 2,100 acts of assault, vandalism and harassment reported by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), a 12% increase from the 1,879 incidents recorded in 2018. On average, six antisemitic acts occurred each day, while there also was a 56% increase in assaults.

The ADL provides the following definition for antisemitism: “the belief or behavior hostile toward Jews just because they are Jewish. It may take the form of religious teachings that proclaim the inferiority of Jews, for instance, or political efforts to isolate, oppress or otherwise injure them. It may also include prejudiced or stereotyped views about Jews.”

California, as of 2017, holds a Jewish population of approximately 1,230,540. In 2019, California accounted for 330 antisemitic acts, placing it among the states with the highest numbers of incidents along with 430 in New York, 345 in New Jersey, 114 in Massachusetts and 109 in Pennsylvania, according to the ADL. These states combined account for nearly 45% of the total number of incidents.

After looking at the survey results and comparing it to widespread antisemitism today, Michelle says that it is “important to acknowledge that while [many] Jews are white-passing, they still receive heavy discrimination,” making an effort to expose the significance of the Holocaust today amongst herself and her peers.

“To me, the Holocaust is a historical symbol of hate towards the Jewish community and how people were able to weaponize that hate to commit mass genocide,” Michelle said. “Since I’ve been brought up in very privileged communities, antisemitism towards me isn’t in the form of violence but more in words and pictures. I’ve seen Swastikas drawn on bathroom stalls, and people have said stupid things to me like ‘have you killed Christ’ or something like that.”

Comparing her own experience in the states to her parents, though, Michelle reflects on how her father’s was much more severe. In fact, Michelle’s father had to change his last name to escape prejudice and hide his Jewish ethnicity when he was brought up in Russia, and only when he immigrated to America did he decide to change his last name back.

Amongst the youth demographic, educational institutions also continue to experience widespread antisemitism. The ADL continues that non-Jewish K-12 schools experienced 411 antisemitic incidents in 2019, a 19% increase from the 344 incidents reported in 2018, and 186 incidents at colleges and universities.

“Even beyond just that person-to-person interaction is this bigger person-to-institution interaction. Take something like the College Board,” Yusupov said. “There is no checkbox for Jewish people, who have been actively oppressed for years and years. You’re labeled as just Caucasian or white or of European descent, or if you’re from Israel, you’re of Middle Eastern descent.”

In fact, Yusupov’s frustration is also directed at a common myth that Jewish people do not experience oppression, simply because they are labeled as white. She believes that national educational institutions such as the College Board can make a greater effort to include the Jewish population to create exposure and recognition for the ethnicity.

“It fails to consider this entire category of people, and that sits very uneasy with me,” Yusupov said. “When someone else looks at me, they say, ‘You’re a white girl, you haven’t been oppressed.’ But half my family died in the Holocaust. This is overlooked in the way that systemic racism that applies to Jewish people is overlooked. To me, that is a very, very big problem.”

Zoe Sanders (’21), who identifies as Reform Jewish, first experienced antisemitism in middle school at the Blackford campus, when one of her friends made an “offhanded” joke about the Holocaust. She felt unsure about how to respond, torn between defending an event significant to her Jewish heritage and maintaining a loose atmosphere around a “joke.”

As she grew older, absorbing more information and becoming more aware of her culture’s history, Sanders often thought back to her middle school interaction. From Sanders’ first synagogue from when she lived in Florida — Temple Dor Dorim — to her current synagogue in Los Altos Hills, California — Congregation Beth Am — Sanders has found a wide array of Jewish community members to learn from and rely on.

“It’s important to me that people recognize the Holocaust,” Sanders said. “As I grew older, I began to connect more with my Jewish roots such as through volunteering at Jewish programs and working with kids who didn’t know as much like I once did, and I found more confidence in speaking up when things that were being said weren’t okay to say.”

At Congregation Beth Am, Sanders met Rabbi Jonathan Prosnit, who was an influential figure in learning more about the Holocaust. Rabbi Prosnit recognizes the value of education in combating antisemitism, such as hearing firsthand from survivors, reading primary documents or even visiting the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C. Some organizations that Prosnit recommends those seeking to find allies or educate themselves more on the Holocaust are Yad Vashem, The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, the Jewish Community Relations Council (JCRC) and the Anti-Defamation League (ADL).

“Antisemitism is a real thing,” Rabbi Prosnit said. “As Jews, we can’t let any hate metastasize. We can’t let jokes, slights, small comments live.”

At the upper school, Pianko notes that antisemitism should be treated in the same way as hate directed toward other marginalized groups — with intolerance. She believes that creating a culture that rejects antisemitism rather than mitigating the effects of discrimination is key to fighting the problem.

“Antisemitism never goes away. It just sometimes falls dormant until it wakes up again. That hatred is just always there,” Pianko said. “Education, engaging with people, understanding this cycle, it’s the only way that people will truly believe that we have a problem and that we need to break this cycle. Antisemitism is something that is happening in our world today, and there’s been an increase. If we want to battle this thing, then we need to know what this thing is.”

An abridged version of this article was originally published in Volume 23, Issue 2 of The Winged Post. On Nov. 13, 2021, this article was awarded 5th place for Social Justice Reporting in the 2021 NSPA Best of Show Award Individual Recognition competition.