The liberal conservative: In conversation with London Assembly Member Andrew Boff

June 18, 2019

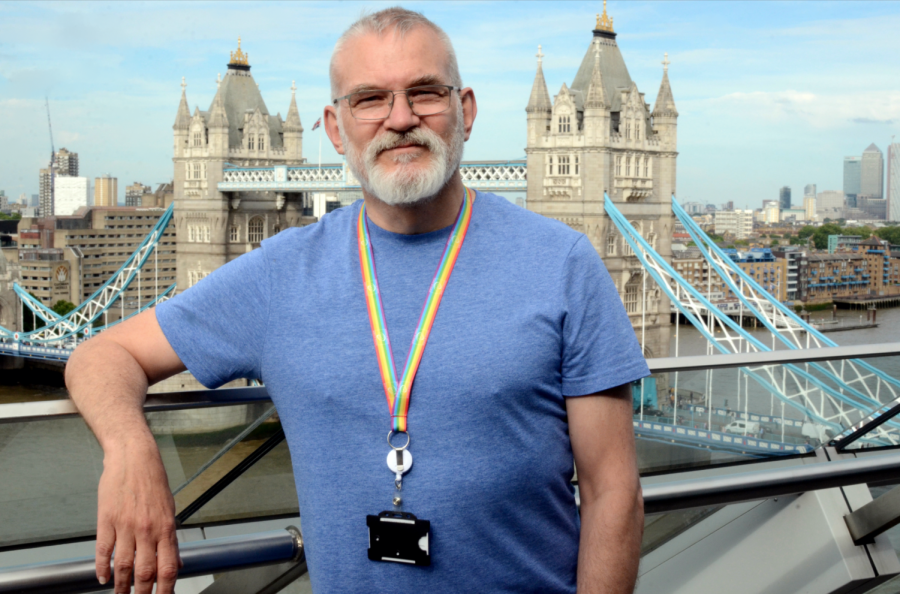

London Assembly Member Andrew Boff stands on the outside balcony of the London City Hall with the Tower Bridge in the background. Andrew Boff is a member of the GLA Conservatives, which includes the London Assembly members that are part of the United Kingdom’s Conservative Party.

Upon meeting London Assembly Member Andrew Boff, he welcomed us into his office and invited us to pour ourselves water from a pitcher on a low glass table. We sat around this table on black leather couches as Boff spoke about his role as an assembly member since being elected in 2008. His office would not strike anyone as out of the ordinary – four unadorned plaster walls, a desktop computer and charging iPhone on an otherwise immaculate desk. Boff himself was plainly dressed, with the exception of a rainbow lanyard that stood out against his light blue T-shirt (in the elevator after the interview, Boff mentioned that he and his husband had been one of the first gay couples to be married legally in London). He spoke in modest terms about his responsibilities, though he represents every district of London, chairs two committees in the assembly and was elected leader of the Greater London Area (GLA) Conservative Group. For the next hour, we discussed parallels in housing issues between London and San Jose and challenges for members of Generation Z in London, among other topics. After the interview, Boff led us on a tour of City Hall, including the speaking chambers, the rooftop viewpoint of London and the lower ground floor, where the entire floor is an enlarged map of the Greater London Area.

Harker Aquila: Can you give us an introduction to your job?

Andrew Boff: [I am a] member of the London Assembly. The London Assembly’s body [is composed] of 25 elected members who are elected at the same time as the mayor of London once every four years. Our job is to hold the mayor accountable [for his policies]. I’m on the right side of the political spectrum, and the London assembly is made up of 11 Conservatives like myself, 12 Labour Party members who are on the left, two Greens, two people from a party that was called the United Kingdom Independence Party, but they have now left that and that’s all a mess, and one Liberal Democrat. And so our job is just to hold the mayor accountable to ensure that he’s doing what he said he was going to do when he was elected, and that the program that he has got is robust.

We have very little direct power. I think we have kind of a nuclear baton. We can reject the mayor’s strategies and plans, or we could reject his budget, or we could reject the transport strategy, or the health strategy or the policing plan. That has never happened in the 19-year history of this body of the Greater London Authority. It’s never actually happened. But the threat of their happening means that the mayor has to respond to our requirements. By law, he has to come and talk to us at least 10 times a year. A lot of the time he evades our questions, but exposing somebody evading a question is actually more powerful than getting an answer.

AQ: Can you talk about how you got into politics?

AB: I came from a political family. My grandfather was one of the founding members of the Socialist Labour Party. My mother was a member of the Conservative Party. And so consequently, I was brought up in a family where people debated. So that was the start of it. And then I became a member of what was called the Young Conservatives at the time I got involved in politics. So at the age of about 15 or 16, I decided that politics was interesting. Then, in 1982, I stood for Council of Hillingdon at the age of about 22 or 23. And so I was a councillor there for 12 years. After that time, I went to leave the council as well, for a period of time, and then stood for Parliament but didn’t get elected. And then in 2008, I stood for the London Assembly, and I became elected.

AQ: So what are you working on right now?

AB: I’ve been strongly involved in increasing the number of family-sized homes that are being built, since overcrowding is a really serious problem in London, much more than any other city in the U.K. We have about 360,000 young people being brought up in overcrowded conditions, and people who are brought up in overcrowded conditions suffer academically and in health terms as well. So I’ve been pushing long and hard for actually all the years that I’ve been on the London assembly to increase the number of these houses that are being built. And that’s very active at the moment, because the mayor of London has to do a London plan, which each mayor of London then refreshes after about four or five years. And he’s doing one at the moment and being very forthright and saying there’s not enough impact. If anything, he’s going to believe a few family size times. So we lobbied very hard with that to ensure that gets changed.

There’s a number of niche areas I’ve been involved with. I’m in favor of drugs regulation because drugs are a real problem in London. You may know that we have had a massive increase in violent crime over the past couple of years, and the police attest to the fact that most of that is due to changes in the drug trade. I think we’ve lost the war on drugs. So from my perspective, it means lobbying politically, it means preparing data, establishing a case that

we need to change our products, [even though] that’s a very big thing to change.

The other thing I’ve been involved with is the change in the way that the police deal with sex workers or prostitution. And that, again, has been over a number of years. [I’m] supporting those organizations who tried to give a voice to people who are in a vulnerable position, mostly women, but some men as well, who find themselves selling sex. The way in which that’s policed before has been very aggressive and pathetic. And so what I did is I got involved in that, and along with other organizations that are representing sex workers, we’ve managed to get the national policing code changed for solid guidance [on] sex work, and a whole host of other things as well. Those are just a few things that I’ve been involved in.

AQ: Something that is prevalent in San Jose is gentrification as a cause of housing prices increasing. Is that a problem here in London, and how are you trying to combat it?

AB: It’s an enormous issue, and there’s a constant pressure of gentrification. And I think you’re absolutely right, many of our cities share the same challenges. It’s useful to look at what other cities do, we don’t do enough of that. In terms of gentrification, one of the public policies here is that any new developments tend to have to have a certain amount of affordable housing. That number, that proportion of affordable housing is subject to political debate. So [the mayor] wants 50% affordable housing, bearing in mind that the word “affordable” is a strange word, I mean, affordable to who? Technically speaking, every home in London is “affordable,” because somebody has afforded them… And there’s other people like myself, who are saying, it’s all very well having that noble aspiration for affordability. But if that prevents new homes from being developed, then actually, you’re doing more harm than good.

The problem is not so much that [wealthier people are] moving into the area and into the homes, it’s just that the local services and the local enterprises then have a new market to appeal to a new bunch of people who could pay higher prices. And that actually means that the prices get higher for people who can’t afford it. So it’s a real struggle. And you’ve got a number of choices, you can either let the market rip and and effectively find cheap homes for people who can’t afford it, or you have some kind of intervention. I think local authorities in the area have just got to keep reminding themselves of who they represent. And they don’t just represent the money. They don’t just represent the newcomers to the area, they have to be able to represent those people who live and live and live and have worked there. And it is a problem. And it is tough.

AQ: Another issue that is being debated in America as well as the rest of the world is free speech and how far that goes, especially with the recent violent incidents against certain religious or ethnic groups. What’s your stance on free speech?

AB: You can use free speech as much as you like. And I know you’ve got it written into the Constitution. Yeah, we kind of have as well, in terms of the European Convention on Human Rights, which the U.K. adopted as its basis for establishing a human rights framework, and just online, you know, that also establishes freedom of speech. There are a few sort-of qualifiers, recognizing that free speech. When you use words as a weapon, that’s not free speech, that’s hate speech.

But I would say that we’ve got as much free speech as the U.S. And sometimes I hear commentary that we haven’t got as much, [but] I think we’ve got as much to be honest. And you can, for example, burn a union jack if you want. That’s not a criminal offense. You can do that here. I wouldn’t recommend it. But you can do it. You can say anything you want about the queen, you can say anything you want about the royal family, about the government ministers, anything you want. Because that’s part of democracy.

A staircase spirals up the north face of the city hall building. Constructed in 2002, the City Hall has a unique round shape on the outside and contains 7300 square meters of glass to provide natural lighting to the interior.

AQ: What is the role of the press in the U.K.? Is it as respected as it is in the U.S.?

AB: I don’t think the press is respected as much here as it is in the States. But our press has something that I think [the U.S. press does not]. They don’t respect status, and they will pursue people. When I see the [American] press interviewing President Trump, for example, [they are] terribly respectful. U.K. press would go for the jugular. They will go straight to a question without showing too much respect for their office. And I know people don’t like that.

However, [one of my colleagues] once said, “Complaining about the media in the U.K. [is] like complaining about the weather. There’s no point; it’s not going to change.” And the good thing about the media is that the media has exposed some pretty atrocious scandals over the ages. So on the whole power, the media does its job, though sometimes it can bring a nasty taste to the application.

AQ: What about student journalism in the U.K.?

AB: I think there’s no real substantial student media. [It’s] not something that we’ve really ever established firmly in the U.K. And I think if it was driven forward, it would be a good thing for us, it’s probably something we should learn from [the U.S.] because I think the good thing about introducing young people to media at an early age is that it teaches them to challenge what they’re being told. And that’s the most important thing: people should challenge all the time what they’re being told, either by the authorities or by the media. So I think the U.S. needs to be proud of this tradition of student newspapers.

AQ: What was your overall impression of Trump’s visit and U.K. politicians’ reactions to his arrival?

AB: When somebody visits, you treat them with respect. However, you shouldn’t hide the fact that you’ve got problems with some of their domestic policy. For example, I can list a whole lot of things where Trump annoys me from some of the things that he’s done. But you know, ultimately, he is the president of the U.S., and he’s got to be respected for that. So ultimately this was kind of about [the mayor] building up his vote base on the basis of opposition to Trump, trying to appear to be the spokesman of decent people.

AQ: Can you speak on the education system of the U.K.? What are the benefits and the areas of improvement?

AB: Our education system has a really great reputation, especially when it gets to university. It’s got a poor reputation in the lower years. You’ll find however that London is the most diverse city on the planet; we will, you know, happily enter a competition with any other city. Well, I say we’re the most diverse because we have 200 languages spoken in London; we’ve got people from every part of the planet making their homes here.

In terms of education, if you take for example, West Africans such as Nigerians, many would prefer to send their children back home for their early education, rather than in an inner city school. That’s because schools in London were particularly bad at one point, and not very good with discipline. However, since they’ve introduced the academy program, and given schools a bit more independence in how they organize themselves, schools have improved remarkably over the last 28 years.

AQ: What is your overall impression of Brexit and its potential impact on the U.K.’s connection with the rest of Europe?

AB: We would be mad, absolutely, as we say in the U.K., stark raving bonkers to put barriers up that prevent people from working in the U.K. There is some argument that we should extend freedom of movement, which we unfortunately, seem as if we’re going to lose as a result of Brexit — this freedom of movement to the Commonwealth countries. So Canada, New Zealand, Australia. And freedom of movement is I mean, people could understand freedom of movement is a right to move, it’s a right to find work in another country. It’s not a permission to go and claims benefits, or social welfare from another country’s, never been that. It’s about freedom to get to go and pursue your dreams, find the opportunities anywhere in Europe, and we would be mad to get rid of that. There’s going to be some kind of reciprocal damage. London is a city of immigrants. I am one of those rare people who was actually born here. But we really are a city of immigrants, and if we stop being a city of migrants and immigrants, then we’ll just decline, it’s as simple as that. We’ll just decline.

AQ: How does the U.K. encourage political activism, and what might be the challenges to getting involved in politics? How are U.K. politics different from that of the U.S.?

AB: We’re finding that people are less willing to commit themselves to a particular political philosophy which may be represented by political party, and more enthusiastic about single-issue campaigns. It’s quite difficult sometimes to turn that enthusiasm into the compromises that you make when you decide to join a political party. Political parties are complex things. They are all coalitions. I mean, I know this is the same to the U.S., if you look at one end of the Democrats to the other end of the Democrats, and they’re nothing like each other. And similarly, you get soft liberal Republicans, where I’d be happier. And then you get the sort of nativist religion-inspired people over at the other end of the Republicans who I just can’t understand. I just, I just don’t get them. And yet, they’re all in their same political parties. And that compromise is quite difficult for young people to come to terms with. And so within my Conservative Party, I’m a liberal conservative. Conservative is the name of the party, but I’m not conservative in the least. I’m more liberal, and other members of my party, in my group that I’m with in this London Assembly, are more about family values and patriotism. We all have got some of that, but it’s about how much you have. And there’s this big realism that you have to come to, when you get involved in politics that you have to compromise. Compromise is not a dirty word. And I sometimes think that young people have a problem with compromise. I was young a long time ago. But I do remember having problems with that kind of compromise, because you can’t think of why you should compromise. But actually getting involved? Incredibly easy, incredibly easy. However, there is a slight difference in that in the U.S. your parties are funded so much more than ours. We have limits on things like election expenses, and stuff like that, and it makes it much harder to get those big powerful machines that you tend to have.

AQ: What will be the biggest challenge for Generation Z students who might want to come to London to work and live?

AB: The biggest challenge for young people who want to come and work in London is housing and accommodation. It’s really, really hard, and I would suggest that it’s one of the hardest places in Europe to get accommodation. Especially if you’re young, and you haven’t got the bank of mom and dad behind you. It can be really, really hard.

And pressure on housing space, obviously, puts pressure on the housing system, which puts pressure on the transport system. And you’ll often find young people who have come to London, and new Londoners, they’re traveling enormous distances, or they have very little money left over from their salaries in order to actually go out and enjoy it. Certainly, if you want to live anywhere around here, and you haven’t got wealthy parents, you’re not gonna have any money to go out, you really aren’t because the rents are so extreme. But people still make their way to London because London is a place where things happen. It’s really just a choice for you to make. I’m very dubious about government that tries to say it’s encouraging enterprise and encouraging companies. I actually think that prosperity happens on its own. It happens when government gets out of the way, not when government has these massive programs of investment. So that generation of people is coming to London. They’ve got a bright future, but they probably won’t stay for long. No matter what, they’re all Londoners, and that’s the important thing. The definition of a Londoner is somebody who by instinct stands on the right of the escalator. And as long as you’re willing, if you come to London, and you want to make your future here, you are welcome.

On August 25, 2019, Harker Aquila conducted a follow-up interview with Assembly Member Boff, asking him about his thoughts on the July 23 election of Boris Johnson as prime minister and its implications for Brexit.

AQ: How has Boris Johnson becoming prime minister and being conservative affected other conservative politicians such as yourself?

AB: He’s a clever politician because Boris Johnson gives the impression that he is a right-wing politician, and many people have tried to compare him with Trump. There really is absolutely no similarity between the two. [Johnson] is someone who’s socially very liberal. That kind of conservatism is the kind that works well in the U.K. The only reservation I have about him is his pursuit of the no-deal Brexit. That’s really the one thing that everybody is talking about in the U.K., and we will be doing so for the next few months.

AQ: In the case of a Brexit with a deal and the case of a Brexit without a deal, how do you see that affecting the London city at large?

AB: It will hit us very badly if there is no deal, and London will be particularly affected because we have very many businesses that are dependent upon free trade and access to the financial and service markets of the rest of the EU. Eventually we’ll recover, but jobs will be lost, the economy will take a dive without a doubt, with no-deal. If we can get a deal that allows us to have access to the EU and yet also permits us to go and do trade deals further afield, then that’s going to be enormously beneficial to us.

AQ: With Boris Johnson as a conservative prime minister, do you see opportunities opening up for conservative politicians such as yourself?

AB: Like most countries, we have to radically reform the way in which we tax the population. We need to reform the economy and constantly try and remove the barriers to enterprise. If we’re going to have an outward looking U.K., one that looks to the world rather than just Europe, then ours are the kind of, some would say, buccaneering policies, free enterprise policies that would benefit our population. When we use conservative government I hope all your readers realize that the words conservative in the U.K. and conservative in the U.S. aren’t directly translatable. Hopefully we can persuade more Americans to understand, that you can be both right-wing in terms of the economy and left-wing in terms of your heart.