Foucault Pendulum

January 31, 2017

Walk into the Nichols Hall rotunda, and the first object that will meet your eyes is the immense pendulum swinging from the ceiling at the center of the room. The circular railing around the pendulum protects the painted figurines knocked to the ground despite their positions all around the ring of blocks at the pendulum’s base. The pendulum’s bob, a sculptured brass sphere, reflects the rotunda’s glazed glass walls as it swings closer and closer to one of the few standing figurines before finally colliding with it.

The display visually demonstrates Earth’s rotation by appearing to travel in a circle and colliding with the wooden figures at its base, painted to represent prominent scientists from a variety of fields.

Originally installed when Nichols Hall was constructed in 2008, the 30-foot-tall pendulum is an example of a Foucault pendulum, named after the physicist who constructed one to demonstrate the Earth’s rotation about its axis in 1851.

“When the building was originally designed, the thought was that the rotunda would have a piece of artwork in it, something representative of the building,” physics teacher Dr. Eric Nelson said. “I brought up the possibility to Diana Nichols of putting up a Foucault pendulum in its place, because it would serve the purpose of being a piece of artwork, but it would also clearly indicate [that] this is a science building.”

Foucault pendulums swing in a fixed plane relative to distant bodies because no external force acts upon them—the pivot point at the top is stationary—showing that the Earth must be rotating to give the illusion of movement.

The pendulum cycles to hit pegs as it moves.

“It is kind of the archetypal science experiment, because it’s the first concrete proof we had that the Earth rotated on its axis,” Dr. Nelson said. “The pendulum swings in a fixed plane relative to the stars. The pendulum does not rotate relative to the Earth. The Earth rotates out from underneath the pendulum, and as you get closer to the equator in latitude, it takes longer and longer for that rotational cycle to complete, and if you’re on the equator, it never rotates.”

Observers on Earth’s surface perceive the plane of oscillation moving with a speed dependent on their latitude: the plane of oscillation of a Foucault pendulum at either pole would rotate in a complete circle in one day, while one at the equator would not appear to shift because of the identical reference frames. The Upper School’s pendulum completes one clockwise rotation around the circle in approximately 40 hours because it is located at 37 degrees 17 minutes north latitude.

“We’re the ones that are moving, but then because we are with the Earth, we don’t perceive that motion. We see it the other way around,” physics teacher Dr. Miriam Allersma said. “It’s easiest to imagine if the pendulum was on the North Pole, then the Earth is completely rotating underneath it, and then you could imagine the pendulum just hanging up there and the Earth just rotating underneath it.”

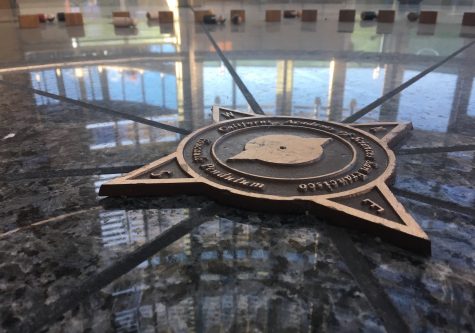

The compass beneath the pendulum.

A magnetic drive system powers the Upper School’s pendulum to prevent friction and air resistance from stopping it, but Earth’s rotation is the sole cause of the illusory rotation of the pendulum’s swings.

“[The pendulum] gets a very, very small driving force, like a child on a swing kicking its legs out at just the right time, that keeps the pendulum going,” Dr. Nelson said. “Otherwise it would just damp down due to friction.”

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek is one of many scientists depicted as the pendulum’s pegs.

Since the first public exhibition of a Foucault pendulum at the Paris Observatory in 1851, the pendulums have become popular scientific exhibits. The United Nations Building in New York City, Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Lincoln Laboratory in Lexington, along with many other scientific museums and institutions, house Foucault pendulum displays.

We stand on the shoulders of miniatures

The Foucault Pendulum’s pegs are actually painted miniatures of influential scientists and thinkers. Here’s a feature on just four of them:

Irene Joliot-Curie (1897-1956) was an influential radiochemist who shared the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with her husband Frederic for their discovery of induced radioactivity: by exposing stable isotopes to specific forms of radiation, stable isotopes can be transmuted into radioactive isotopes.

Joliot-Curie was the daughter of renowned scientists Pierre and Marie Curie. Her two children, Helene and Pierre, are also established scientists.

Linus Pauling (1901-1994) was a prolific quantum chemist and biochemist as well as a peace activist. He is one of only four people to have been awarded more than one Nobel Prize, and the only person to have been sole recipient of both.

He won the 1954 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work developing orbital hybridization theory and won the 1962 Nobel Peace Prize for his activism advocating nuclear disarmament.

Democritus

Democritus (c. 460-370 B.C.E.) was an ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher known for theorizing that the universe is composed of indivisible units called “atoms” which are constantly in motion, separated by empty space and indestructible. All objects are formed from the reconstitution of “atoms.”

Though none of his works survive as primary sources, he was a prolific writer on ethics, epistemology, etiology, astronomy and mathematics.

Maria Mitchell

Maria Mitchell (1818-1889) was the first female professional astronomer in America.

Mitchell discovered “Miss Mitchell’s Comet” in 1847, achieving fame across the western world. For this discovery, she was awarded a medal by the King of Denmark, who gave prizes to the discoverers of comets too faint to be observed with the naked eye.

The Maria Mitchell Observatory at her birthplace of Nantucket, Massachusetts, is dedicated in her honor.

Foucault’s other work

French physicist Jean-Bernard-Leon Foucault is best remembered for giving his name to the Foucault pendulum, which he prominently displayed in 1851, but he also made several discoveries in optics and mechanics.

Together with fellow French physicist Armand Fizeau, Foucault was able to take detailed photographs of the surface of the sun. He independently developed a method of measuring the speed of light that involved a lens, a stationary mirror and a rotating mirror, and he showed that light moved faster in air than in water, disproving theories of a constant velocity.

His other innovations in optics included a method to measure the curvature of telescope mirrors and a light polarizer known as the Glan-Foucault prism.

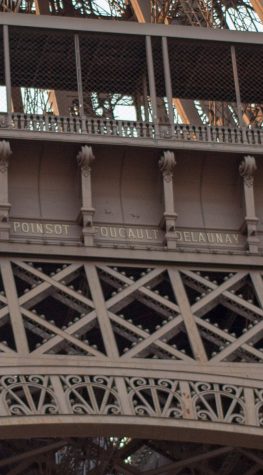

Foucault also named the gyroscope and demonstrated the existence of eddy currents, sometimes called Foucault currents, generated within conductors by magnetic fields. His name is one of 72 French scientists’ engraved on the Eiffel Tower.