Behind the Statistics: Students stories of survival in Silicon Valley

January 8, 2017

Editor’s Note: I would like to express my gratitude for the students and alumni who decided to share their stories in this piece. Mental health is a deeply personal topic, and it takes more than a little courage to talk about these experiences. Although most of the subjects approved the use of their actual names for this article, Wingspan’s strategic leadership chose to keep them anonymous. Currently, our culture is in the process of shifting from a position in which those with a mental illness were stigmatized, but we’re not there yet, and until we are, Wingspan will take the necessary steps to protect its sources.

***

Another student dead. Two suicide clusters in five years. Parents fear their child is next. Teachers blame academic stress. CDC called in. Where was the epicenter of this maelstrom of pain? According to one writer, right here.

In December 2015, The Atlantic published a piece entitled “The Silicon Valley Suicides,” documenting suicide clusters in the Palo Alto area. The article painted a grim picture of the story behind the success of Silicon Valley’s youngest generation, with anecdotes of adolescents pushed to suicide by the pressure cooker of academic stress.

The piece tells the story of a community — the broad trends that led to a tragic loss of 232 teens from 2003 to 2015 — and the efforts to heal and help the living. In an immediate response to a suicide cluster in Palo Alto at Gunn High School and Palo Alto High School, former English teacher Marc Vincenti and Gunn student Martha Cabot formed a group in 2014 called “Save the 2,008,” aiming to create hope for Palo Alto’s high school students by proposing an action plan to reduce stress in the classroom.

But there are other important elements to the story of mental health in Silicon Valley that often go overlooked. This is a story about the individuals that make up the statistics, about living in the face of death. This is a story about how Silicon Valley kids survive.

***

In Silicon Valley, stories of mental illness are often linked to or triggered by the high-pressure academic environment.

For Tammy, that wasn’t the case. With a flushed face and a love of hugs, Tammy endears herself to people effortlessly, offering support and a shoulder to cry on for friends and acquaintances alike. She began displaying mild depression in sixth grade, then hypomania her eighth and ninth grade year. At the beginning of her sophomore year at a rigorous Silicon Valley private high school, she crashed into major depression.

“That’s when I started struggling with rapid cycling bipolar, which is when you have more than four episodes in a year,” Tammy said. “I was cycling between depression and mania; within a month I would go through a cycle of each. That’s very damaging to your brain, so it’s not healthy to be in that state.”

Tammy spent the rest of sophomore year working with doctors and trying different medications, with mixed results. At the end of the summer, she cycled from mania into depression again and attempted suicide. After being rushed to the emergency room and recovering in the hospital, she left with a renewed purpose to beat her mental illness.

“Because of the regret I felt after doing that [attempting suicide], I was re-inspired to live,” Tammy explained. “I started working really hard to live and find hope in any situation. That’s been rough and not always easy, but I’m definitely in a better place today than I was before.”

Tammy left her high school after her suicide attempt, and she is currently in an intensive outpatient program. She emphasizes the importance of assistance battling mental illness.

“It takes a lot of support from professionals to fight something like this,” she said. “But you also have your friends and your family, and even your acquaintances. There are people who care about you and want you in their life, no matter how small of an impact you think you’re making on them.”

Reflecting on the help she received from those closest to her Tammy thinks that the most helpful conversations from loved ones are the trivial ones.

“It’s so important to hear those things and to keep thinking about those things, because those are the kind of things that we live for: the little things. We just have to keep living our life, so we have to enjoy the small things,” Tammy said. “Keep talking to them like they’re a human being. Don’t treat them any differently because they’re struggling. Just exist as a friend and always talk to them and never give up on them.”

But, Tammy acknowledged, it’s difficult to be a mental health ally.

“It might be really hard to be friends with someone who is struggling with mental illness because they’re going to try to reject you. They try to isolate themselves. I know I definitely tried to isolate myself from my friends, and it was really hard for them to just keep supporting me even though I was trying to reject that support. I am so grateful that they continued to support me, because that’s exactly what I needed at the time,” she said.

To someone struggling with mental illness currently, Tammy offers some advice.

“It’s going to sound horribly cliche to say this, but really, you are never alone. You always have people supporting you, even in the darkest hours. There is never a reason that you have to completely give up, because there is always hope. There is a hope that is great enough and big enough and strong enough for every single human being on this planet.”

***

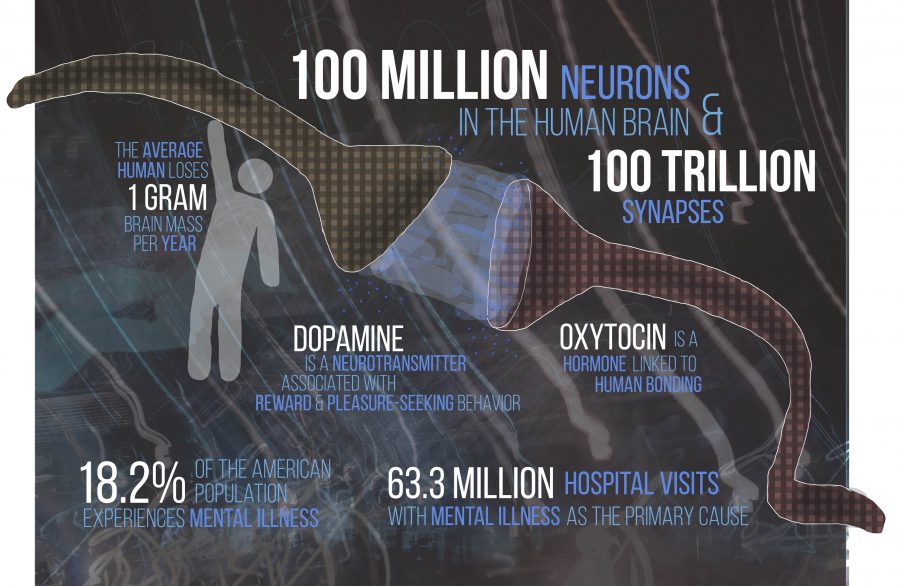

According to survey results collated by the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), half of the cases of disorders that humans suffer from in their lifetime begin by the age of 14. Twenty percent of adolescents from ages 13 to 18 struggle with mental disorders.

The importance of these key formative years in the mental development of young adults cannot be discounted, especially in high school, according to University of San Diego School of Leadership and Education Sciences Assistant Professor Dr. Erika Nash Cameron.

Dr. Cameron has worked in counseling various demographics ranging from primary school students to university graduates, considering the different ways in which students may face personal adversity through their developmental years. Currently, she serves as an educator for future counselors.

“If you were to take underclassmen in a high school, there’s going to be a different set and intensity of problems than maybe what a junior and senior may see. When you get to junior or senior year, it’s now a bit more high stakes, especially depending on the high school that you’re in. If it’s one that’s very much a college-going group, you’re going to see more signs of anxiety surrounding college applications, AP courses, Honors courses, things like that. Juniors and seniors are going to be more on edge in that regard,” Dr. Cameron said. “Whereas, a freshman coming into that hasn’t gotten to that anxiety and may very well be involved in the transition of now going to high school and figuring out the dynamics that are going on in the high school and what crowd do you hang with and what teachers are good, so it’s going to be a different level of intensity.”

Although specific sources of anxiety vary among individuals and ages, adolescence as a whole is a stressful time, with pivotal mental development and the strain of high school combining to an immense pressure.

***

“All of a sudden you’re very on edge, and it’s very hard to pay attention. You become hyper aware of everything around you, you’re just very stimulated. Everything seems so consequential when really it’s not at all.”

Nidhi is a high-achieving Harker upperclassman whose ardor for learning is matched only by her enthusiasm for social justice. With a quick gait and seemingly boundless physical energy, she gestures eagerly when elaborating on one of her passions.

She also struggles with anxiety and panic attacks, like the one described above.

“I’m someone who is aggravated by small things,” Nidhi explained. “If I see someone in my class understanding something more quickly than I do, and responding more quickly to questions, and I’m still completely confused, I take that very personally and I’m all of the sudden making really dramatic assumptions, like now I’m not smart at all, like I’m not competent enough for this class.”

According to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America, anxiety disorders affect 18% of the population, making them the most common form of mental illness. It’s mostly commonly characterized by excessive worry about everyday events and tasks.

“I get to a point where I’m not really in control of those thoughts that I’m having, and I get very anxious and just very overwhelmed for a kind of stimulus that wasn’t so strong to begin with,” she said.

In her junior year, Nidhi’s anxiety began to increase, especially in the face of a perceived culture of ‘excellence without effort’, in which students minimize time and effort spent studying, in upper level math and science courses.

When her teachers became concerned about her fluctuating emotional state, they referred Nidhi to the counseling department, which recommended she see a therapist.

“When it was first suggested to me that I see a therapist, I was very set against the possibility. I guess I saw having a therapist as a sign of weakness or I perceived it as meaning I couldn’t cope myself, I couldn’t handle it myself. Looking back on it, it must have been a product of my stigmatizing mental health issues.”

Despite her initial misgivings, Nidhi has found her therapist very helpful, especially in helping her understand how she thinks.

“I have disproportionate reactions, I stop consciously thinking the steps that lead me from the stimulus to the response, all of those are things that my therapist helped me understand,” she said. “I think almost knowing what’s happening to you on a more psychological level helps you rationalize it and take steps towards resolving it. If you personally go back and try to reverse those neural pathways, maybe eventually you’ll get to the point where your brain doesn’t fire in that way.”

Since starting therapy second semester of her junior year, Nidhi has been working on finding coping mechanisms to help manage her anxiety.

“It sounds so cheesy and almost insincere to just say you should think positive thoughts about yourself, because most of the time you can’t come up with anything positive if you’re in that mental state. Honestly, I wish I had more illumination on this subject,” Nidhi said.

“The only thing you can really do is be aware of what it is that’s going on in your mind and treat it seriously as opposed to just ‘Wow, I don’t cope well’ or using those trivializing statements,” she said. “Knowing that, at least when I do have a breakdown, I’m not like ‘Wow, I’m crazy.’ It’s more like, ‘That was a hard day and this is what happened.'”

As Nidhi finishes senior year and prepares to venture into the world, she does so with a dedication to finding a more stable mental state.

“You can have a great mental health and be maintaining a really positive mental state, and you’re still going to have bad days. What I hope is that one day I can get to a point where I have proportionate responses to the things that go wrong,” she said.

***

The Harker counseling department can be easy to miss – it’s a small nook of a building nestled in a corner of Shah. Anyone who enters one of the individual counselors’ offices is greeted by warm lighting, plush rugs, couches and candy.

“We’re going for cozy,” said Greg Roumbanis, one of Harker’s counselors. Lori Kohan and Greg Roumbanis, two of Harker’s three academic counselors, both hold master’s degrees in psychology. Kohan is also a licensed marriage and family therapist; Roumbanis is a marriage and family intern.

Both had strong personal motivations to go into counseling.

For Kohan, a 40-something woman with an elegantly tousled brunette bun and a prodigious supply of fuzzy cardigans, counseling isn’t so much a career as a way of life.

“I’ve known my entire life,” Kohan said. “In high school I was a peer counselor. I’ve been doing this job for 25 years. I was licensed in 2000. To get licensed, you need 3000 clinical hours; I did 6000. I’ve worked in group homes, hospitals, clinics, public schools, private schools, private practice, but my passion has always been high school kids, to try to be there for them in a way that people were for me.”

For Roumbanis, 39, a slim muscular man with salt and pepper hair and a soft smile, his interest in therapy stems from a time of personal crisis.

“When I was about 17, my parents divorced. I remember at that age in my life, I really felt like I needed someone, but stigma was a huge reason why I didn’t reach out to somebody,” he recalled.

“Once I finally did, it made a huge impact on my life. In my mid-twenties, I realized what I was doing with my career path wasn’t really fitting for me, and I kept going back to the fact that I really wanted to reciprocate [the support I got] back to someone else, and be there for someone else when they needed. It led me to the path I’m on now,” he said.

A Harker counselor’s job is two-pronged: each counselor acts as both an academic adviser, providing tutoring resources and time management help, as well as an emotional support system. Often, the two are intimately related.

“The amount of stress that you guys experience on a daily basis, both academically and social-emotionally, is tremendous. Everything is intertwined. If a grade dips, it’s very rarely because of a lack of understanding of the material,” Kohan said.

“Each student and each family is unique, 3-dimensional, and it’s so important for us to try and understand exactly what that is, where they’re coming from. What works for one person is going to be the antithesis of what works for another person,” she said.

On a daily basis, counselors talk to students and the parents, teachers, coaches and other adults in those students lives, as well as further correspondence by email. Of the students who have appointments, the majority are referred by a friend or teacher.

“The training we try to do with students is where is that line between ‘I’m here to support you, you just had a bad breakup, eat a tub of ice cream with me’ versus ‘You’re really not okay, you’re really not enjoying the things you used to love, I think this is bigger than both of us, and if you’re not ready to go tell someone, maybe I am,” Kohan added.

Harker provides numerous resources for anyone who is struggling.

Each student identification card renewed at the start of every year has three hotlines on the back: the Teenage Health Resource Line (1 (888) 711-TEEN), the YWCA 24 Hour Rape Crisis Line ((650) 493-7273) and the Suicide and Crisis (24 hours) ((408) 279-3312). The three anonymous and confidential phone numbers make up the “Teen Resource List” provided to every student.

“We did that 10 years ago because you guys take those cards with you everywhere,” Ms. Kohen said. “If you’re alone, and you feel like you’re not safe, use one of those numbers. You’re not alone. Let’s find a way to get you connected, because part of what goes on often is that isolation, that you feel like no one else is going through this, no one else is in as much pain, no one else can understand.”

“If you’re in isolation, you can’t change it. You can’t get better,” Mr. Roumbanis said.

Although they guarantee confidentiality to an extent, Harker counselors must follow legal provisions, as must all counselors in California: if someone might imminently harm himself, others, or be harmed, you are legally obligated to break confidentiality.

***

Non-symmetrical shapes. Out-of-tune music. Mentions of death, cancer, suicide, rape. All of these are triggers for Katherine, a student who fights with anxiety, paranoia, obsessive- compulsive tendencies and depression.

“I want to beat mental illness every single day. I put me against my brain against chemicals in my brain,” Katherine said. “Sometimes it works and I come out on top, and sometimes my brain comes out on top and I have to learn to be okay with that. To be okay with those discrepancies.”

Every day, Katherine greets her peers and teachers with wide eyes and a bright smile as she marches through Harker’s halls. She began struggling with self-harm in middle school, when she had negative experiences in her search for professional psychological care. Afterwards, it was difficult for her to trust adults with her illness, something she’s been working on throughout high school.

“I think I am getting a lot better with that now,” she said. “I trust one of my past teachers, and one of my current teachers. I think that as long as I have a support system of adults, if I ever am in danger that I will have someone to go to.”

Katherine acknowledges that it’s difficult to know the best way to protect student safety.

“There are things that students may be afraid of telling you for fear of retribution,” she said. “There are people who love their abusers and don’t want them to go to jail. There are things that students won’t tell you. But they also won’t want you to tell their potential abusers the things that you know about them.”

For herself, Katherine copes by focusing on the future. When she feels unwell, she talks to a friend about their plans together.

“What we plan to do during college and the kind of house that we are planning to live in together,” Katherine said of the things they talk about. “The kind of pets that we want to get. Just the idea that there is a better future out there than the present I am living right now is really comforting and will help me get through.

To anyone currently battling mental illness, Katherine offers words of support.

“You are all valid. The things that you go through are valid. Do not consider yourself weaker than others because of what you go through. The fact that you are surviving day by day with these imbalances in your brain, these neurochemical imbalances in your brain means that you are waging an internal war with yourself and you are winning.”

***

In addition to the counseling services provided at most area high schools, other groups have also formed in Silicon Valley in response to concerns of stress and mental health issues.

Recently, Nadia Ghaffari, a junior at Los Altos High School, began a new initiative in early 2016, aimed at stimulating more conversation around mental health issues and putting faces to stories.

She created TeenzTalk as a direct response to The Atlantic’s article on Silicon Valley’s suicide clusters, which she learned about in her AP Psychology class. Right now, Nadia’s team at TeenzTalk aim to post videos with the stories of teenagers from around the globe who are struggling with mental health issues and are willing to share their stories.

“I wasn’t really seeing anyone take severe action. It should stand out to everyone that a suicide cluster is not okay and shouldn’t be happening,” Nadia said. “What I was trying to do was work with other teens in creating a positive community environment where they don’t need to worry about those pressures of educational norms and school. It’s just a place for us to inspire each other, and it’s all teenagers. We’re eliminating the generation gap and just focusing on teen-to- teen connection.”

After spending time at Yale last summer, Nadia’s project has expanded to include teenage ambassadors around the globe who have been spreading the mission behind TeenzTalk. Her team includes 11 ambassadors from India, Ghana, Switzerland and other countries, all of whom are interested in encouraging the conversation around mental health.

“I started talking to people from Pakistan, Ghana, and Tanzania, and I realized that they are also going through the same stress, experiencing the same stressors,” Nadia said. “I opened my eyes to this new aspect that this was a global issue. Teen stress isn’t just here in Silicon Valley: it’s literally everywhere.”

***

The summer before his junior year, Dylan, then a Silicon Valley public high school student, took an East Coast college tour with his parents. The academic opportunities were exciting, but as Dylan began to get attached to the ivy-covered buildings, he also felt the mounting stress of the requirements and achievements necessary for admission.

“I approached my junior year in high school with a lot of uncertainty over whether I could meet my parents’ and now preferred colleges’ expectations,” Dylan said.

Dylan is a slim dark-haired boy who hunches over when he works, absorbed by the problem at hand. Gregarious and easy to talk to, he listens to anyone who needs to talk. Dylan had always been held to a high standard by his parents, but at the beginning of his junior year, he started spending more time with the more competitive students in his class. Peer, personal and parental pressure, combined with a strenuous course load, finally compounded into an unmanageable anxiety level.

“Parental expectations definitely influence [my stress levels]. You feel the pressure to do what your parents expect of you, always, because they give you so much,” Dylan said. “This kind of competitive stress coupled with family expectations seriously made me feel cornered to perform better and reach an even higher degree of achievement.”

Dylan initially used exercise and sports as coping mechanisms, but even those became sources of stress with he failed to make the varsity tennis team second semester junior year. Going into senior year, college decisions proved another source of anxiety for Dylan.

“This seems to be the worst kind of stress because there is nothing you can do about it. You just have to accept it,” Dylan said. “But I also I discovered that sharing my problems with friends helps to improve my mental state, particularly concerning my interpersonal relationships.”

Dylan graduated from last year and is now a freshmen at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign majoring in Electrical Engineering. Looking back on his high school experience, he believes that he was lucky in the support systems he found.

“[Counselors] seem to be available at school and having known a friend that benefited from a counselor, it helped me to find help in a similar fashion,” Dylan said. “I do believe the support system is there. But in regards to society accepting and helping people with mental health, I just think that we are not going to see it soon.”

***

Across all sources interviewed, student and adult alike, one theme repeats: reach out to someone. It can and will get better.

“Talk to someone you trust in an adult role. It doesn’t have to be us,” Harker’s Kohan advised. “Talk to somebody who can do something. You don’t have to fight alone.”

“Go get help. Go seek out somebody. Don’t suffer alone and in silence,” University of San Diego’s Dr. Cameron said. “Find safe friends or parents or adults you can connect to and reach out to them. If they don’t hear you, find another until someone is actually listening to you.”

***

Tiffany doesn’t so much walk around campus as bounce, muscular legs propelling her from class to class.

Early in her freshman year, Tiffany was diagnosed with anorexia. Despite a few episodes of hospitalization, she continued to finish off her freshman year with minor interruptions. However, in the summer before sophomore year, she struggled with a bout of weight loss, leading to her missing two months of her sophomore year at Harker. As a result, Tiffany left Harker for another local public school to finish off her sophomore year, with the goal of returning to Harker.

“I wanted to come back to Harker just because I liked it better, and Harker said ‘Okay, we’ll take you back as long as you redo sophomore year like we told you originally,’” Tiffany said. “And I was like ‘Okay, it’s worth it,’ but then throughout that sophomore year in [my new high school], I knew that to come back to Harker, I needed to get better, so it was a lot of me telling myself what was important, what was just in my own head.”

While away at her new school and out of therapy, Tiffany researched her illness, talked to other teenagers to try and learn more about how the science behind her illness, and tried to keep her mind off her own body to focus on gaining back weight.

“[It felt] like everything you do seems wrong. You want to eat because you know it’s right, but then once you eat, even if it’s a grape, it’s not okay, you want to go hide in a corner and not eat for the next two days to compensate,” Tiffany said. “Once you have a meal or something, just go do something else right after. Don’t think about it. It’s not going to hurt you.”

Tiffany also ran an Instagram account through which she was able to talk to people who were in the same situation as her.

“I was never going to see myself the way that other people saw me, the way I actually looked,” Tiffany said. “So knowing that what I was saw was not what I looked like, it helped a lot.”

Now, Tiffany can be found roaming the halls of Harker with friends, having successfully returned to Harker to redo her sophomore year and now attending the school as a junior. Part of her life now involves reaching out to others who are struggling and talking to them about their situation , as well as extending a hand to help as an ally through her Instagram.

“In a way, technically, [my biggest ally] was myself, which sounds sad, but it wasn’t because it’s the only way I got out. Relying on other people didn’t help me because it would be that I could only rely on them for this amount of time, and then I would realize it wasn’t helping,” Tiffany said. “Also, [it helped] just talking to people in the same situation as me. That helped because I knew other people thought the exact same way I did. It’s so weird, but you’re never alone.”’

***

The Atlantic’s “The Silicon Valley Suicides,” reduced Bay Area high schoolers to a few thousand words that caricatured students as stressed, privileged children collapsing under the weight of academic pressures. But, as each person’s story here reveals, students in the Silicon Valley are more than their struggles.

Each individual in this article is so much more than what we’ve been able to represent. They have friends, favorite subjects, life dreams, pet peeves – young people with full lives. We are each more than what words and statistics represent, and we’re working everyday to survive. That, like the stories of the incredible people in this piece, deserves recognition.

This piece was originally published in the pages of Wingspan on December 14, 2016.