The contrarian’s constraint

November 10, 2016

There are Trump supporters in our community.

It may be hard to believe, and even harder to imagine. But make no mistake – there indubitably exist non-facetious local Trump supporters. But they are silent – and wisely so, for they are vastly outnumbered would face sharp censure from their peers should they make their sentiments known.

These regional political minorities cannot make their voices heard – when overwhelmed by a majority, a contrarian vote amounts to nothing. This is a result to the unique structuring of the electoral college.

In reality, the American voting process is not truly democratic. When citizens cast their votes at the poll, they aren’t directly voting for their candidate – instead, they’re voting for regional electors who have pledged their votes to a candidate. It is these electors that comprise the 538 votes for president.

However, these electors are awarded per state in a quantized, discrete fashion. A single state may be contested neck and neck, but ultimately all of that state’s votes will be awarded to only one candidate (except for the exception states of Nebraska and Maine). That 48 percent of the popular vote ascribed to the losing candidate in a hotly contested state is worth nothing. No electors are awarded in their name, and half of an entire state’s opinion is wholly disregarded.

This effect greatly dampens voter turnout. Minority voters aware that their candidate will lose in their state may feel discouraged from voting, believing that it cannot influence the election – somewhat rightly.

For example, California is very left – the chance of Trump winning the state was practically zero. Even though there are easily hundreds of thousands of Californian citizens who would have voted for Trump, their votes are ultimately meaningless, and many of them acknowledged that. Clinton would take California, and any individual’s vote for Trump couldn’t have changed that outcome. The converse attitude holds true as well – many of those who would have voted for Clinton in California, confident of her victory, didn’t vote.

This harsh reality dampens voter turnout in both directions. Contrarian voters, outnumbered, may opt not to vote out of fruitlessness. And in more extreme cases, the complacency of majority voters can cause a statewide upset.

Moreover, the electoral vote is unequal. Each state is assigned a number of electors based on its population, but the voters per elector ratio is variable throughout each state.

An elector in California represents about 700,000 voters – but a elector in Wyoming represents about 200,000 voters. What this amounts to is that the Wyoming citizen’s vote effectively counts three times as much as the California citizen’s vote. This broad trend is observed between the larger states and the smaller states, giving the residents of smaller states undue influence in the election.

I believe that a viable and appealing way to amend these shortcomings without completely overhauling the electoral college is by regionalizing votes to counties.

Within a state, individual counties show great variability in alignment. For instance, while the overall state of Tennessee voted overwhelmingly Republican – according to the New York Times, 65.5% to a Democratic 30.6% – individual counties were strongly Democratic. Davidson County, the district containing Nashville, voted 60.4% Democratic to 34.3% Republican.

By having these individual counties represent electoral votes instead, minority voters would gain greater representation even when greatly outnumbered within a single state. The term of “minority” is also somewhat misleading – the losing party often commands as much as 30% of the vote, or even up to half. This is the great injustice of the electoral college – that such a large portion of the voting constituency literally does not count in the electoral college at all.

This change would increase voter turnout by legitimizing contrarian votes, creating a more democratic voting process.

Moreover, we might expect benefits from increased voter turnout beyond the presidential election. Minority voter apathy resulting from their lack of representation creates a culture of abstaining, spilling over into other elections as well. But by reassuring voters that their votes truly matter, they will be encouraged to participate in other votes as well.

Voters’ opinions and actions would be able to effect greater change in the election – a regional minority would be able to rally their surrounding community in support of their cause and actually change the outcome of their county’s vote. But in the current system, this is impossible – no regional activist can reasonably persuade an entire state.

Altogether, the localization of electoral votes would increase regional participation both in voting and in political organization.

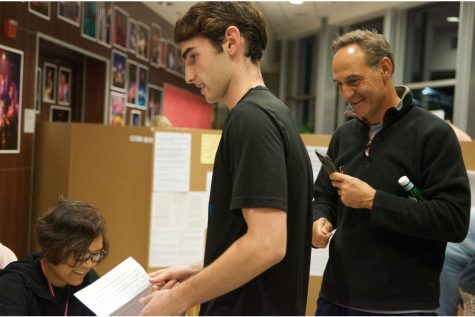

First time voter Nick Haidar arrives at a Westmont Highschool poling place with his father, who takes pictures of this significant moment in his son’s citizenship Tuesday evening.