Homework, Work, Work, Work, Work

October 14, 2016

In August, a second grade teacher from Godly Elementary School in Godley, Texas decided to send home a letter to parents explaining that she would assign no homework and proposing that students instead spend time with their families, eat dinner together, read for pleasure and sleep more.

Her letter went viral on Facebook, and a number of elementary schools from Seattle to Tulsa to San Diego to Boston have also chosen to follow a “no homework” policy.

Educators at these schools are following research such as Alfie Kohn’s “The Homework Myth” that indicates that homework does not provide any benefit, especially at the elementary age level.

“Overall, we’re seeing, especially in the elementary school, a lot more people sort of questioning the value of homework in elementary school, besides asking kids to read for pleasure,” said Denise Pope, co-founder of Challenge Success and senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education.

Pope has extensively researched the impact and uses of homework, and her organization, Challenge Success, hosts workshops for parents and teachers about recommended homework policies.

The lower school has made changes to its homework policy to reflect focused assignments and reduced time requirements.

“[Our policies] have changed a little bit over the past several years in that the number of minutes that we’re asking the children to devote homework has been reduced a bit but not to the exclusion of homework altogether because we feel homework is a very integral part of our curriculum,” Sarah Leonard, Primary Division Head, said in a phone interview.

“At the top of my list, homework is meant to design to reinforce and extend work that has been introduced in class. Second, we feel homework promotes the development of organizational skills and time management skills. We are trying to promote the idea that learning is an ongoing process and that it extends beyond the walls of the classroom,” Leonard said.

The debate on the benefits of homework has continued for decades. Researchers have approached the homework debate from several different angles, investigating the potential academic benefits and health impacts of varying amounts and types of work.

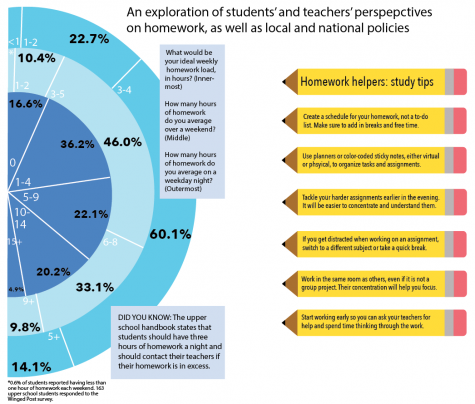

An exploration of students’ and teachers’ perspectives on homework, as well as local and national policies.

“What we’ve discovered is that when students have fewer classes each day, even though they’re in school for the same amount of hours, they can actually focus more on that topic,” Pope said. “You’re only supposed to then only have homework in the classes that you have the next day, so that’s supposed to really reduce homework stress instead of having homework in every class every night.”

In recent years, schools around the country, including the upper school, have changed old policies and enacted new ones with students’ well-being in mind.

According to the upper school handbook, the duration of students’ nightly homework should not exceed three hours, after which students are encouraged to communicate with their teachers about the issue.

Although 17 percent of 163 upper school students who responded to a Winged Post survey indicated that no homework would be ideal, 36 percent prefered one to four hours a week.

“I joke about [no homework], but I don’t really think that’s a great idea,” Aditya Dhar (12) said. “I think that homework is important. There should be exceptions—everyone learns in a different way, and I don’t know if homework really helps everyone learn in the same way. But I do think that homework is generally important.”

Twenty-two percent of respondents reported they would prefer five to 10 hours of homework, 20 percent preferred 10 to 14 hours and five percent saw 15 or more hours of homework a week as ideal.

“I think that less homework would be nice, overall, but I just don’t think it’s going to happen, especially at this school,” ASB President Sandip Nirmel (12) said. “If you want to prepare kids for college, where homework is going to happen no matter what, then homework at lower stages is beneficial.”

Sandip’s sentiment about the necessity of homework was echoed by teachers.

“[Adopting a no-homework policy] going to be tough, because every subject needs more time than what you can allocate in school,” computer science teacher Anu Datar said. “You are here for either 255 minute periods or 170 minutes periods per week, and then if I have to cover something that actually takes five hours, it’s just impossible to do that unless I have to send some work home or you have to come in for office hours.

The ongoing dialogue about homework has sparked research into ways that teachers can keep students engaged both in and out of school.

One specific trend intended to increase student engagement in class and at home is a modified block schedule, such as the bell schedule that the Upper School switched to at the beginning of the year.

On a modified block schedule, courses meet on alternate days of the week for a longer duration of time and is similar to the full block schedule which is common at American colleges and universities.

“[The schedule has] moved to the little bit closer to a college model, which I prefer,” English teacher Christopher Hurshman said. “Especially with reading, it helps because it means that there’s always something interesting to discuss, whereas sometimes we were limited to 30 to 40 minutes of homework every night. It was pretty hard to have something that was meaty enough to justify our class conversation, so I personally like it better that way.”

Another alternative teaching method is the flipped classroom model, where students learn material at home, typically through short, pre-recorded lectures, and use class time to ask questions or discuss the content.

“I think that if we have students learn material at home and then ask questions in class, there would be less motivation to actually do the homework, when students can just go to class and ask questions,” Joanna Lin (11) said. “Even worse, I think some students might never participate in class, and others might move off topic.”

With no concrete methodology for employing the flipped classroom model, its specifics differ based on specific classes.

“If we keep in mind that when students listen to teachers, they retain less than if students do their own learning, I think that the flipped classroom is pretty genius,” world history teacher Mark Janda said.

“This is in the sense that it forces students into the position of using the information, using the content, finding a way to explain the content and to teach their peers. I think that they end up with greater retention and a deeper knowledge of the content than if we just have the sage-on-the-stage sort of situation,” Janda said.

While trends like a modified bell schedule and the flipped classroom method may contribute to a more manageable homework load, a balance is likely the best answer in the end, according to education researcher Pope.

“We really have to be clear that everyone has got to be part of the solution,” Pope said. “The students, in terms of what they’re doing while they’re doing their homework and how busy their days are; the parents, in terms of what they’re allowing kids to do; and the teachers, in terms of what they’re assigning.”

This piece was originally published in the pages of The Winged Post on October 11, 2016.