College and beyond: moving to the big league

February 19, 2015

For Ramya Rangan (‘12), her first taste of CS involved mapping the Upper School’s intricate web of social interactions in her sophomore year. After Dr. Marcel Salathe, then a postdoctoral scholar at Stanford, visited campus, Rangan became fascinated with his project of modeling the spread of an epidemic across a school’s networks.

“It was inspiring that this was a very real problem that we could actually face,” she said in a phone interview. “I probably already knew this, but it just hit me that I couldn’t manage to understand those sorts of data sets without using CS.”

From there, Rangan pursued her interest by taking AP CS and two advanced topics courses at the Upper School. She now majors in CS as a junior at Harvard University and has felt largely supported by her mentors and peers on both high school and college campuses.

“A large part of my involvement with math and science in middle and high school was the presence of really inspiring peers,” she said. “Some of my closest friends were really into things like Mathcounts in middle school or math and science related things in high school.”

Although her school experiences have been encouraging, her experience off campus, in the tech workforce, has been less positive.

In the summer after her freshman year at Harvard, Rangan interned at San Francisco’s Yelp, which provides platforms for information and reviews about businesses. She was one of two females in an intern group of about 50 people.

“Unfortunately the gender balance post-college is quite a bit worse than what I’ve seen at Harvard,” she said. “A lot of the science classes at Harker are pretty balanced with some exceptions, but we were lucky to grow up in an environment where we didn’t have to face such stark gender inequality. ”

Women who earn STEM degrees, like Rangan, are faced with job placement as the next step, and according to the U.S. Department of Commerce’s 2011 Executive Summary of Women in STEM, women held only 24 percent of all working positions in STEM fields, even though women hold 48 percent of all jobs.

The disparity leads to disparagement, according to Tess Rinearson, a software engineer at blogging platform Medium and an attendee at Battle of the Hacks 2014 at the venture capital firm Andressen Horowitz, a programming invitational representative of over 50 events promoting innovation for college students.

“It’s something that people don’t want to talk about. It’s kind of the elephant in the room,” Rinearson said as one of five women out of 27 hackathon attendees in the room. “I’ve had lots of miscellaneous experiences where [I think,] ‘God, I wish there were more women in tech because this behavior is unacceptable.’”

A Seattle native, Rinearson graduated from Lakeside High School and took classes at University of Pennsylvania and Carnegie Mellon before leaving college after a year to pursue a job at Medium.

Her experience as a 21 year-old female in the tech world has led her to describe the industry’s culture of microaggressions as experiencing a “death by a thousand papercuts.”

Last year, Tess experienced a more in-your-face example of the sexism present in tech.

“I was supposed to be judging this hackathon. I talked to this team one-on-one, and I was really enthusiastic about this team’s hack,” she said. “As I walked away I heard one of them say, ‘She wants the d—,’ which is totally inappropriate.”

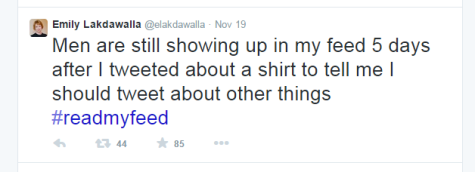

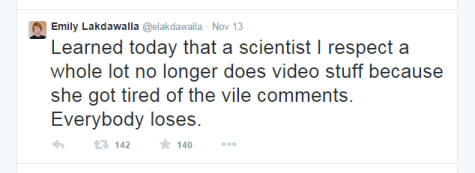

For women in careers that require an online presence, microaggressions often occur in the form of Internet harassment. Planetary geologist Emily Lakdawalla, who currently works as an editor and evangelist for The Planetary Society, an organization involved in advancing space exploration, discusses and promotes science through social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter.

Emily Lakdawalla spoke at the FameLab event at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference.

“When you’re on the Internet and you’re a female, you know it,” she said in a Skype interview. “It makes a difference. You get creepy comments. Initially I blew them all off, and over time it starts to get heavier and heavier, and you just don’t want to deal with them anymore.”

Writer and former physics student Eileen Pollack said combatting microaggressions that women bear while in a male-dominated field will help increase the number of women in tech. Pollack, who in 1978 became one of the first two women to earn a Bachelor of Science in Physics degree at Yale, published in The New York Times Magazine “Why Are There Still So Few Women in Science?” in 2013. Next year, she will publish her memoir, The Only Woman in the Room: Why Science Is Still a Boys’ Club.

“There are studies that say that women leave voluntarily because they want ‘people fields,’ and to this, I say, ‘There are no people in engineering?’” she said in a phone interview. “Engineers and chemists and computer scientists work in teams. There’s an idea that women walk away from the fields voluntarily, and that’s nonsense. [They are] already struggling under so many burdens every day where they feel they don’t belong. You would only not want to get women and minorities if you believed that they were inherently not as gifted in tech.”

Females leaving or being unable to enter tech positions is not just an issue of social fairness but also an issue that impacts earning potential over a lifetime. According to Forbes, the highest paying jobs for college graduates are in engineering, with a median starting pay of $53,400.

Even in the field, females earn less than their male counterparts—a 2012 American Association of University Women report stated that on average a female in engineering makes 88 percent of what a male does when both are one year out of college. Overall, in 2013, females still earned 78 cents for every dollar males earned.

Among the CS world, hackathons might still help in facilitating wider access, said Jon Gottfried, 23, the founder of Major League Hacking, the official college hackathon league.

“Ultimately, the solution is to make tech friendlier to newcomers, whether that’s people who are less experienced, or simply people who have been doing technology on their own and haven’t been part of this community yet,” he said. “I think that hackathons can do a lot to change how people get introduced to technology and to the startup world.”

According to Forbes, valuations of startups are at an all time high, as today nearly 40 startups are worth more than $1 billion in 2013. However, according to a 2013 report from Pitchbook, a data provider for venture capitalist markets, only 13 percent of venture capital deals had at least one female co-founder.

“The big focus should be on how to get more women and people of color hired and in leadership positions at tech companies,” Kat Manalac, a partner at prominent seed accelerator Y Combinator, said in an email interview. “I’m encouraged because I’ve started to see a lot of smart people devoting their time to building solutions. The emphasis should be on action.”

Seed accelerators like Y Combinator provide seed funding in exchange for an equity share in a prospective startup. Manalac said Y Combinator received 5,000 applications last year, but only around one in four of the companies had a female founder. In response, Y Combinator launched its first Female Founders Conference last March with 450 attendees, involving a host of female founders sharing their stories. The next one is slated for this February.

“Our hope is that highlighting the stories of these successful women will encourage more women to take the leap and get into entrepreneurship themselves,” Manalac said.

The story of one such woman’s career in tech started at a New York bank. After studying electrical computer engineering at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), Ruchi Sanghvi, age 33, arrived at her new math-modeling job and experienced a change of heart.

“I got a little bit of a panic attack,” she said. “I wanted to work in a place where I would be contributing to the very core of the company. I wanted to be building the product that would go out of the company and not the support functions.”

This revelation brought her to become the first female engineer at Facebook in 2005. While there, she worked to develop the Newsfeed and the Facebook Platform, allowing third-party developers to add their applications to the network. As one of five females studying engineering at CMU, she did not find her experience as the only female in the workplace particularly surprising.

“As you are part of a team, often men are just more comfortable going out to a bar and grabbing drinks with other men,” she said in a phone interview. “It’s very rare that you would see a male manager with a female coworker out at a bar grabbing a drink. A lot of work is based on trust and not just professional trust but also trust that you’re able to build socially, and those are implicit biases.”

In 2010, Sanghvi left Facebook to start her own company, Cove, and joined Dropbox in 2012. In October 2013, she left Dropbox to pursue personal projects.

In a fast-paced industry like tech, Sanghvi encourages females to stand their ground.

“The tech industry is a really powerful industry to be in because you can have impact immediately, and you can impact billions of people,” she said. “Don’t be afraid to voice your opinion. Don’t be afraid to ask for opportunities—raise your hand and ask for those opportunities. When you’re offered a seat on a rocketship, don’t ask which one, just take it.”