The Gender Gap: Why women in STEM get lost along the pipeline

February 3, 2015

She sits down in the last open seat of the Neural Networks computer science classroom in Nichols Hall—middle table, last row. The two adjacent tables and the three in front each have two to three of her male classmates clustered around them, immersed in code. The male teacher walks around, answering occasional questions.

These 11 boys had been Anika Mohindra’s (‘16) companions in the advanced topics course she took in the first semester of her junior year. A post-AP class, Neural Networks introduces students to artificial neural network technology and its applications.

Anika Mohindra (16) is the only girl in her Computer Science class.

“I remember when I walked in on the first day, I thought, ‘Oh, I’m the only girl in this class,’ and that made me a little nervous,” Anika said. “I know gender disparity is a problem, so letting it affect me makes me feel a little deficient.”

Computer Science (CS) Department Chair Dr. Eric Nelson taught the class the last time it was offered six years ago. With two degrees in physics, he has previously worked in corporate research environments and at astronomical observatories. He said that the students’ choice of seating is voluntary, as he has no seating chart, and noted the strong gender discrepancy is not typical in Harker’s CS classes.

“[Last] semester was unusual, [with] only one [girl] in each section,” he said. “This semester a third of the class (out of 18) is girls. Each girl handles the situation differently. Some work alone, and others are highly interactive with the other members of the class.”

AP CS teacher Susan King, 62, similarly encourages students to find work partners on their own. In her observation, students tend to favor working with members of the same sex.

“We work in partners a lot, and I want people to be comfortable with their partner,” King said. “Have I observed females particularly getting isolated by a bunch of males? Yes, I have. I’ve observed it in a number of schools. It hasn’t happened in a class of mine at Harker.”

King received her Bachelor of Science degree in CS from Montana State University in 1975, at a time when 19.8 percent of such degrees were conferred to females, according to the National Center for Education (NCES).

“I certainly know what [being isolated] is like,” she said. “I was often the only female in math classes or CS classes.”

That was 40 years ago, but the disparity continues. Anika’s experience as the minority gender reflects a broader downward trend of gender equity in technology.

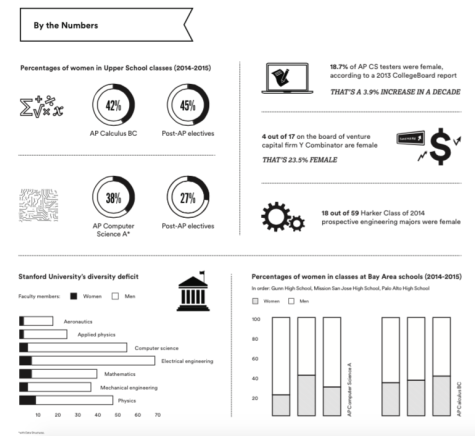

Contrary to what intuition might indicate, as increasing numbers of women earn degrees in business, biology, and physical sciences, the number of CS degrees received by women today is less than a third of what it was 30 years ago. In 2011, 18.2 percent of bachelor’s degrees in CS were given to women, compared to 37.1 percent in 1980, according to the NCES 2013 Digest of Education Statistics.

The term “pipeline” has become used throughout the industry with regard to how women become dissuaded from pursuing technology fields. Women are lost bit by bit through a pipeline that constricts as they move from early education through the subsequent years to employment age.

Harker positions itself as a “world-class institution” in the heart of Silicon Valley, the tech capital of the U.S. With 64 percent of last year’s female graduates self-reporting a plan to major in a STEM field, according to survey responses collected for The Winged Post’s college map, many already encounter or will go on to face gender disparities within these fields as they move along the pipeline.

Starting early in the game

The Middle school programming club run by Mr. Michael Schmidt has no girls on the team.

Some students may know her as the eighth-grade girl arriving at the Upper School each morning for her AP Calculus BC class and ninth-grade English class.

Rose Guan’s (‘19) primary interest lies in biology, but she has also enjoyed the various math and CS electives available at the middle school. Last year, she was a member of Programming Club.

“For required classes, the gender disparity doesn’t exist,” Rose said. “But in programming club last year, when we met, I was the only girl and there were around ten other boys in the club.”

Programming Club, an extra-curricular, is run by Michael Schmidt, the head of the Middle School’s CS department. This year, the club is all male.

“There were two girls that came for a while, but they were drowned out by the boys,” Schmidt said. “That is one detriment to girls when trying to work in a group with boys. They’re not as assertive. I don’t think that is a negative, but I think it translates to the same problems that exist in the working world of technology.”

To counter the problem, Schmidt considers starting a girls programming club next year.

“The only difference I have seen [between the genders] is that there are a handful of students that enter my class as seventh graders who already have had experience programming,” he said. “That ratio of boys to girls is imbalanced, with boys being the majority. I don’t know if this is based on true interest and personal motivation, or if their parents are pushing them towards the topic of programming.”

Parental views might hinder young girls from STEM classes based on preconceived biases about whether girls can participate in the field. A 2011 University of Chicago study titled “The Role of Parents and Teachers in the Development of Gender-Related Math Attitudes” found “that parents’ and teachers’ expectancies […] are often gender-biased and can influence children’s math attitudes and performance.”

Having grown up with a now 20 year-old brother, a 15 year-old brother, and a 10 year-old sister, Chandini Thakur (‘16) sees a different emphasis on the STEM interests of males and females in her family. She plans on becoming a medical doctor, and her older brother studies computer engineering in college.

“My dad has already started working on getting my younger brother connected to people in engineering and not as much on my future career in the medical field. It’s interesting to see that because my sister’s already expressing an interest in engineering, and he’s not paying attention to that as much as he should be,” she said. “It’s just kind of disappointing sometimes that gender can get in the way of interests that children may have in science.”

At the middle school level, Schmidt and the administration are aware of the gender imbalance, with CS electives consisting of an estimated three boys to one girl. A course introduced last year to the curriculum, “Programming Fundamentals” is a required 7th grade course intended to even out the playing field.

“If [girls] see that it’s well within their reach to try more programming related tasks, those numbers may equalize,” Schmidt said. “We’re hoping that getting this education to students earlier will give girls the confidence and desire to challenge themselves in the high school when it comes to programming.”

Taking it to the next level

Nitya Mani’s (‘15) interest in STEM began at a young age, when her parents read her Richard Dawkins’ books on evolution. Love for math especially was a consistent part of her childhood. Since her years at Joaquin Miller Middle School in San Jose, she has done math research, taken a slew of advanced math and CS courses, and competed in math contests.

As Nitya puts it, she “grew up on the math team.”

Like Anika, Nitya for the past semester has been the only female out of 13 in her advanced topics course in CS, Numerical Methods.

“I was the only girl [on my middle school math team] until Anika came to our school, and so I’m used to associating with guys. I sit with guys at the table,” she said. “I think that Harker is one of the few places where there are so many girls who do classes in CS. There are fewer [girls], but it’s definitely better than other places.”

According to Head of Academics Jennifer Gargano, enrollment in the Upper School’s science departments such as Biology and Chemistry are relatively equal, and the courses following AP CS are 60 to 70 percent male.

Nationwide, CollegeBoard has noticed a disparity between the genders in AP CS exams and a less severe one in AP Calculus BC exams. In 2013, 18.7 percent of AP CS test-takers and 40.5 percent of AP Calculus BC test-takers were female according to the organization’s annual report.

“Historically there have been a disproportionate number of males taking AP Exams in CS A,” said Amy Wilkins, CollegeBoard’s social justice consultant, in an email interview. “Last year alone nearly 300,000 students with the potential to succeed in an AP course did not take one.”

Compared to other schools where Science Department Chair Anita Chetty has taught, Harker’s classes are more balanced in terms of both numbers and classroom dynamics. Before coming to the Upper School, Chetty taught AP Chemistry and AP Biology at a public school in Calgary, Canada, where class sizes exceeded 30 students.

“Harker, I think, does not represent what may be happening out there. Teachers are very mindful of teaching the individual,” she said. “At the public school, when you have large class sizes on a daily basis, it may be easier for a teacher, from my own perspective, unless you consciously make an effort, to just call on the first person who raises their hand, and it could be a boy over and over and over again, but you might not notice that.”

As a teacher, Chetty has learned to pay attention to these sorts of dynamics. She recalls differences in reactions to girls’ and boys’ classroom participation in her years as a student.

“If boys made a mistake, people laughed it off,” she said. “If you were a female, you felt as though if you made a mistake it was not going to be funny. It was like, ‘You’re dumb.’”

Chetty’s interest in STEM led her to earn a B.S. in biology from the University of Calgary in Canada in 1979 and two degrees in STEM education—a Bachelor of Engineering in education leadership at the University of Lethridge and a Master of Engineering in secondary science at the University of Portland.

As in Chetty’s observations, differences in attitudes towards disappointment have continued to perceptibly divide students along gender lines.

Dr. Puragra GuhaThakurta, an Astronomy and Astrophysics professor at University of California at Santa Cruz (UCSC) and director of the Science Internship Program (SIP) over the summer, observed different reactions to outright failure from the males and females in his classes.

“Girls often blame themselves for failure whereas boys blame the thing that failed,” he said. “You encounter a difficult math problem and the girls will say ‘I don’t get it, I must not be good enough for math,’ whereas the boys say the teacher teaches badly.”

His comments are rooted in research discussed in Dr. Diana Kastelic’s dissertation for the University of Denver, “Adolescent Girls’ Support for Voice in Education.” In her paper, Dr. Kastelic writes, “When boys fail, blame is placed on external factors, while success is attributable to ability. Surprisingly, girls’ achievement is attributed to luck and hard work, and failure is blamed on lack of ability.”

Nitya refers to these and other subtle barriers against women pursuing STEM as “implicit discouragements.” She mentioned comments she received last summer from a university professor alongside a male classmate who was also interested in investigating research opportunities for pure math.

“[The professor] told the guy about the opportunities, and then he told me that I should look at the pre-med department, because that would be a better place for me,” Nitya said. “There’s a lot of things that people do to implicitly discourage you. Now, it’s not so much [from pursuing] STEM, but to discourage women from pursuing pure STEM fields.”

For women and other minorities entering STEM, microaggressions, such as the one Nitya faced, are often the result of unconscious bias. The term microaggressions has recently received more public attention, with Psychology Today defining it as “the everyday verbal, nonverbal, and environmental slights, snubs, or insults, whether intentional or unintentional, which communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative messages,” in this case, to females.

From high school to college

After graduating from high school and beginning a major in STEM fields at campuses across the country, demographics in classrooms grow increasingly worse for females as they proceed along the pipeline in college.

Biology major Samantha Hoffman (‘13) walks into the seminar room for her Computational and Mathematical Engineering (CME) class at Stanford University. What strikes her as odd is the composition of teaching assistants for the class.

“For both my CME classes, 100 percent of the TAs were male,” she said.

Hoffman, who plans to add a sub-concentration in neurobiology and a minor in creative writing, views the TA imbalance as an important issue to fix, due to female mentorship’s importance in encouraging female participation in STEM fields. Various organizations at Stanford, including She++ and Women in CS (WiCS), have been started in order to combat existing social barriers against women.

“The biggest problem is getting mentors, because without mentors, you can’t really get your advice. You can’t really get those connections to help you move forward in the industry,” Hoffman said. “In big companies, leadership [consists of] only one out of five or one out of ten women depending on what industry you’re in, and so you have to get change started there.”

As former Upper School Math Department Chair and Middle School division head, as well as a math teacher at other public and private schools, Head of Academics Jennifer Gargano stresses the importance of teachers as role models and guides. Throughout her study of math education during college, she was encouraged by professors who assumed she would go on to earn a master’s degree even before she had planned to.

“It’s the teachers that really have so much power in terms of turning students onto a course that they thought they may not have interest in, or keep them loving a subject, too,” she said. “I think it’s all about the teachers.”

Finding a mentor for women in the worlds of academia can prove challenging on campuses like Stanford, where only three out of 54 of the CS department’s full-time faculty members are women, as the Winged Post discovered by counting the department’s faculty on its website directory.

Sean Treichler, a male summer teacher and past teaching assistant for Stanford University’s CS143 course in compilers, said he was confident that rectifying the gender balance in faculty was a continued goal during recruitment.

“A significant challenge on this front is that the gender mix for new Ph.D.s in CS seems to be lagging [in the number of women], so demand [for female faculty] will constantly exceed supply,” he wrote in an email interview.

College and beyond: moving to the big league

For Ramya Rangan (‘12), her first taste of CS involved mapping the Upper School’s intricate web of social interactions in her sophomore year. After Dr. Marcel Salathe, then a postdoctoral scholar at Stanford, visited campus, Rangan became fascinated with his project of modeling the spread of an epidemic across a school’s networks.

“It was inspiring that this was a very real problem that we could actually face,” she said in a phone interview. “I probably already knew this, but it just hit me that I couldn’t manage to understand those sorts of data sets without using CS.”

From there, Rangan pursued her interest by taking AP CS and two advanced topics courses at the Upper School. She now majors in CS as a junior at Harvard University and has felt largely supported by her mentors and peers on both high school and college campuses.

“A large part of my involvement with math and science in middle and high school was the presence of really inspiring peers,” she said. “Some of my closest friends were really into things like Mathcounts in middle school or math and science related things in high school.”

Although her school experiences have been encouraging, her experience off campus, in the tech workforce, has been less positive.

In the summer after her freshman year at Harvard, Rangan interned at San Francisco’s Yelp, which provides platforms for information and reviews about businesses. She was one of two females in an intern group of about 50 people.

“Unfortunately the gender balance post-college is quite a bit worse than what I’ve seen at Harvard,” she said. “A lot of the science classes at Harker are pretty balanced with some exceptions, but we were lucky to grow up in an environment where we didn’t have to face such stark gender inequality. ”

Women who earn STEM degrees, like Rangan, are faced with job placement as the next step, and according to the U.S. Department of Commerce’s 2011 Executive Summary of Women in STEM, women held only 24 percent of all working positions in STEM fields, even though women hold 48 percent of all jobs.

The disparity leads to disparagement, according to Tess Rinearson, a software engineer at blogging platform Medium and an attendee at Battle of the Hacks 2014 at the venture capital firm Andressen Horowitz, a programming invitational representative of over 50 events promoting innovation for college students.

“It’s something that people don’t want to talk about. It’s kind of the elephant in the room,” Rinearson said as one of five women out of 27 hackathon attendees in the room. “I’ve had lots of miscellaneous experiences where [I think,] ‘God, I wish there were more women in tech because this behavior is unacceptable.’”

A Seattle native, Rinearson graduated from Lakeside High School and took classes at University of Pennsylvania and Carnegie Mellon before leaving college after a year to pursue a job at Medium.

Her experience as a 21 year-old female in the tech world has led her to describe the industry’s culture of microaggressions as experiencing a “death by a thousand papercuts.”

Last year, Tess experienced a more in-your-face example of the sexism present in tech.

“I was supposed to be judging this hackathon. I talked to this team one-on-one, and I was really enthusiastic about this team’s hack,” she said. “As I walked away I heard one of them say, ‘She wants the d—,’ which is totally inappropriate.”

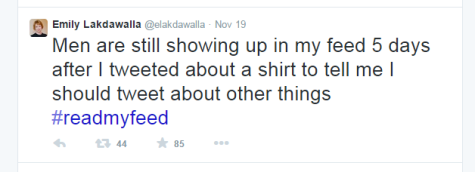

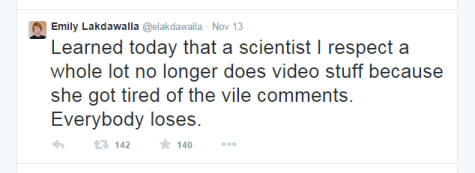

For women in careers that require an online presence, microaggressions often occur in the form of Internet harassment. Planetary geologist Emily Lakdawalla, who currently works as an editor and evangelist for The Planetary Society, an organization involved in advancing space exploration, discusses and promotes science through social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter.

Emily Lakdawalla spoke at the FameLab event at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference.

“When you’re on the Internet and you’re a female, you know it,” she said in a Skype interview. “It makes a difference. You get creepy comments. Initially I blew them all off, and over time it starts to get heavier and heavier, and you just don’t want to deal with them anymore.”

Writer and former physics student Eileen Pollack said combatting microaggressions that women bear while in a male-dominated field will help increase the number of women in tech. Pollack, who in 1978 became one of the first two women to earn a Bachelor of Science in Physics degree at Yale, published in The New York Times Magazine “Why Are There Still So Few Women in Science?” in 2013. Next year, she will publish her memoir, The Only Woman in the Room: Why Science Is Still a Boys’ Club.

“There are studies that say that women leave voluntarily because they want ‘people fields,’ and to this, I say, ‘There are no people in engineering?’” she said in a phone interview. “Engineers and chemists and computer scientists work in teams. There’s an idea that women walk away from the fields voluntarily, and that’s nonsense. [They are] already struggling under so many burdens every day where they feel they don’t belong. You would only not want to get women and minorities if you believed that they were inherently not as gifted in tech.”

Females leaving or being unable to enter tech positions is not just an issue of social fairness but also an issue that impacts earning potential over a lifetime. According to Forbes, the highest paying jobs for college graduates are in engineering, with a median starting pay of $53,400.

Even in the field, females earn less than their male counterparts—a 2012 American Association of University Women report stated that on average a female in engineering makes 88 percent of what a male does when both are one year out of college. Overall, in 2013, females still earned 78 cents for every dollar males earned.

Among the CS world, hackathons might still help in facilitating wider access, said Jon Gottfried, 23, the founder of Major League Hacking, the official college hackathon league.

“Ultimately, the solution is to make tech friendlier to newcomers, whether that’s people who are less experienced, or simply people who have been doing technology on their own and haven’t been part of this community yet,” he said. “I think that hackathons can do a lot to change how people get introduced to technology and to the startup world.”

According to Forbes, valuations of startups are at an all time high, as today nearly 40 startups are worth more than $1 billion in 2013. However, according to a 2013 report from Pitchbook, a data provider for venture capitalist markets, only 13 percent of venture capital deals had at least one female co-founder.

“The big focus should be on how to get more women and people of color hired and in leadership positions at tech companies,” Kat Manalac, a partner at prominent seed accelerator Y Combinator, said in an email interview. “I’m encouraged because I’ve started to see a lot of smart people devoting their time to building solutions. The emphasis should be on action.”

Seed accelerators like Y Combinator provide seed funding in exchange for an equity share in a prospective startup. Manalac said Y Combinator received 5,000 applications last year, but only around one in four of the companies had a female founder. In response, Y Combinator launched its first Female Founders Conference last March with 450 attendees, involving a host of female founders sharing their stories. The next one is slated for this February.

“Our hope is that highlighting the stories of these successful women will encourage more women to take the leap and get into entrepreneurship themselves,” Manalac said.

The story of one such woman’s career in tech started at a New York bank. After studying electrical computer engineering at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), Ruchi Sanghvi, age 33, arrived at her new math-modeling job and experienced a change of heart.

“I got a little bit of a panic attack,” she said. “I wanted to work in a place where I would be contributing to the very core of the company. I wanted to be building the product that would go out of the company and not the support functions.”

This revelation brought her to become the first female engineer at Facebook in 2005. While there, she worked to develop the Newsfeed and the Facebook Platform, allowing third-party developers to add their applications to the network. As one of five females studying engineering at CMU, she did not find her experience as the only female in the workplace particularly surprising.

“As you are part of a team, often men are just more comfortable going out to a bar and grabbing drinks with other men,” she said in a phone interview. “It’s very rare that you would see a male manager with a female coworker out at a bar grabbing a drink. A lot of work is based on trust and not just professional trust but also trust that you’re able to build socially, and those are implicit biases.”

In 2010, Sanghvi left Facebook to start her own company, Cove, and joined Dropbox in 2012. In October 2013, she left Dropbox to pursue personal projects.

In a fast-paced industry like tech, Sanghvi encourages females to stand their ground.

“The tech industry is a really powerful industry to be in because you can have impact immediately, and you can impact billions of people,” she said. “Don’t be afraid to voice your opinion. Don’t be afraid to ask for opportunities—raise your hand and ask for those opportunities. When you’re offered a seat on a rocketship, don’t ask which one, just take it.”

Steps ahead

Nitya and Anika both see themselves moving forward in the male-dominated field, confident that things will change by the time they are in graduate school.

“I think that the only way to break the gender gap is to get in when you’re the minority gender,” Nitya said. “I feel fine, because there are going to be enough women around me. By the time that I get a Ph.D., there will be a lot of women with me, because I think it’s changing.”

As a senior next year, Anika plans to take the CS advanced topics courses Expert Systems and Computer Architecture, as well as the advanced mathematics topics courses Differential Equations 2 and Signals and Systems.

“I think within a decade we’ll definitely have a lot more women in higher positions in STEM, and having those leaders as examples will provide yet another push for women to enter the fields,” she said. “Once the fields start evening out, I’m confident that they’ll progress until they reach equilibrium, however long that may take.”

Female alumni have gone on to success in STEM fields. Forbes’ 2014 “30 Under 30” list in science and health care featured Surbhi Sarna (‘03), who founded nVision Medical, a technology intended to improve ovarian cancer detection. Currently, several of the most prominent Bay Area tech companies are led by female Chief Executive Officers such as Susan Wojcicki of Youtube, Marissa Mayer of Yahoo, and Meg Whitman of Hewlett-Packard. Sheryl Sandberg, Chief Operating Officer of Facebook, and Marissa Mayer declined an interview with The Winged Post.

Women currently in the industries foresee an influx of women entering STEM fields in the next five to ten years. For Emily Banks, lead mobile news editor of the Wall Street Journal and previous managing editor of Mashable, her introduction to tech began in the midst of her career at Mashable when she analyzed traffic to the site and learned programming. With the increased relevance and use of coding skills today, Banks sees more women taking these roles on, though change may be slow.

“We’ll still see more and more women stepping across the gap from the “softer” tech fields fully into tech, but they may be like me, without any formal (as of yet) STEM training,” she said. “They’ll be like my Journal colleague who previously managed the daily news production of the iPad app and crossed over to the tech side to be a product manager. But these roles as hugely important. Having these women pave the way means a more welcome workplace for women who choose to major in tech fields too.”

At Harker, Head of Academics Jennifer Gargano said she has explored some of the existing opportunities or initiative organizations that the Upper School currently has in order to improve any imbalance, including WiSTEM (Women in STEM), which was created 10 years ago to address female underrepresentation in higher-level math and science classes.

Improvement, according to her, is still on the agenda moving forward.

“I think we have a lot of really accomplished females in those areas. Why wouldn’t we want to push forward those efforts?” Gargano said. “We can do better, and we should do better.”

This piece was originally published in the pages of WingSpan on January 28, 2015.