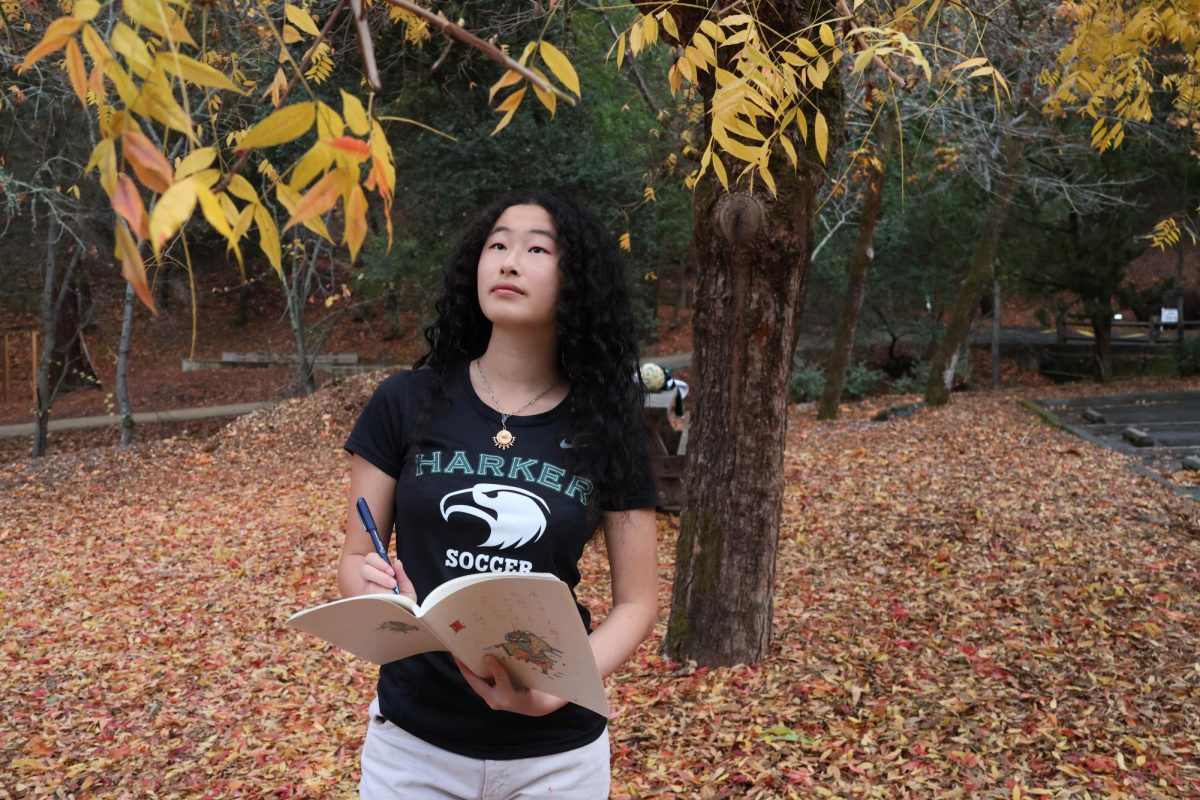

Humans of Harker: Watercoloring the past

Aryana Far (12) uses art to examine societal flaws

Anoushka Buch

“Whenever we visited Iran, I had to wear a hejab to cover my hair, [and] as a kid, I never understood why. I realized, through reading and asking my parents questions, that it was a symbol of repression of women. I wanted to represent that [repression] in art, because it was so prevalent in my family. I did collages to shed light on the negative impacts [of the culture],” Aryana Far (12) said.

A brush makes an organic, watery magenta stroke on thick paper, the first line on an otherwise pristine sheet. As time goes on and the color dries, the brush retraces its strokes on the paper and creates new ones, each swirl of color part of a bigger piece: a woman’s face, her beautiful eyes focused upon the viewer in a powerful, unwavering gaze.

Now look up, and you’ll see Aryana Far (12) working on her latest watercolor portrait. The woman on paper looks almost exactly like Aryana herself with her defined eyebrows, shapely nose, and full lips, save the cloth covering her hair and the expression on her face, one that hints at fear.

After taking AP 2D Studio Art in her junior year, Aryana has committed herself to exposing the flaws in society that she observes, specifically the repression of women, through her art. Aryana’s paternal grandfather was liberal and non-religious, and he served as a general in the former Shah’s army. As a result of his position, he was forced to go into hiding and his family fled the country.

“[After my grandfather was released] he worked as a lawyer [in Iran] to help the common people. He had to pretend that he supported the Islamic regime, but he wanted to help people, so he made [those] personal sacrifices,” Aryana said. “Every time I visited him when I was younger, everyone knew my grandpa – the grocers, the bakers, the bankers. He was always helping others, even when he faced hardship.”

Growing up in a family who struggled through and fought in the Iranian Revolution, which spanned from January 1978 – February 1979, helped Aryana detect the remnants of emotional impact still influencing her relatives’ everyday acts.

“People who’ve experienced the revolution [react] in different ways. My family leans towards rejecting oppression,” she said. “The women in my family work, [are] artists, vote, and raise their children like badasses. They’ll always remember their history, and it’ll affect how they act, but I couldn’t be happier to be raised by such resilient women.”

The revolution was the transition from authoritarian monarchy to a totalitarian Islamic theocracy. The U.S. did not support the change in government, and its violent aftermath affected the women in Aryana’s family tremendously. Though she didn’t experience the event firsthand, Aryana noted that specific cultural traditions highlight the revolution’s ramifications, as its leaders placed heavy emphasis on the hejab and imposed strict legislation that further restricted women’s rights.

“Whenever we visited Iran, I had to wear a hejab to cover my hair, [and] as a kid, I never understood why,” Aryana said. “I realized, through reading and asking my parents questions, that it was a symbol of repression of women. I wanted to represent that [repression] in art, because it was so prevalent in my family.”

As one of Aryana’s closest and earliest friends, Heidi Zhang (12) observed the impact of the revolution on Aryana and her family.

“On the first day of kindergarten, we became best friends because we were both wearing pink dresses, and we’ve been friends ever since,” Heidi said. “[The Iranian Revolution] is a really big part of her identity because she sees [the aftermath] every day.”

After finding photos of the her mother and aunts in situations that reflected this suppression and learning more about the constrictive acts that were simply regarded as ‘part of a culture,’ Aryana decided that she wanted to go further and expose the impacts those acts had on women, specifically those in her family, which she did by juxtaposing the photos she had found in her watercolors.

Finding a photograph of her mother modeling a big stack of pearls led Aryana to begin thinking about beauty standards and how they affected women. She then began to channel this thought and energy into her painting.

“I depicted my mother in watercolor with the pearls wrapped around her neck and shoulders, strangling [her]. Placing that next to the original photograph, I felt that I was dramatizing the symbol of pearls in a subtle way,” Aryana said. “I wanted this piece to start a conversation about beauty standards.”

Aryana’s mission of exploring societal flaws carried over to her work in AP 2D Studio Art, where she chose to create a collection of nine pieces which all traced the theme of women’s cultural repression. Her pieces “Handcuffs” and “Menstruation” reflected women’s suppression and the societal stigma surrounding female development, respectively.

Not only was Aryana inspired by the “hand-me-down” effects that the Iranian Revolution had on her family, but literal hand-me-down clothing from her older relatives prompted her interest in fashion and clothing.

“Since I’m the youngest, I always [received] my family’s hand-me-downs. I didn’t mind, though. I liked wearing clothing with a story,” Aryana said. “As I grew up, I became more conscientious about consumer culture and unethical practices in the clothing industry, so I kept with the theme of wearing clothing with a story. I started thrifting, upcycling, and sewing. I value sustainability and ethical production, so I embody that in what I wear, and I have fun with it.”

Aryana’s family played a large role in shaping her character. Aryana’s father, with his enthusiastic outlook towards learning, also affected Aryana’s own perspectives.

“I grew up having my dad come back from philosophy conferences and talking about Nietzsche and all those other crazy things I didn’t understand,” Aryana said. “He would work on electrical engineering inventions at night, just always doing something to enrich his own mind. I admire that, and I want to do that too.”

Her close friend Kelsey Wu (12) noticed that Aryana’s aspiration to constantly be learning was reflected in her personality and behavior towards those around her.

“A lot of people have seen her art or heard her singing, but academically and as a friend, she’s always wanting to learn about your life and what you’re doing,” Kelsey said.

Aryana’s goal to deepen her understanding of the world manifests itself in her attention to the little details in her work, her personality, and the other aspects of her life; visual arts teacher Joshua Martinez noted Aryana’s tendency to constantly try to improve.

“She has this really wonderful ability to critique herself without making herself feel bad,” Martinez said. “She has this resiliency, which is the hardest thing for an artist to teach [herself] to do. She’s found a way to work through a lot of strategic problems which make a lot of [other] artists back off.”

![Setter Emma Lee (9) sets the ball to the middle during the match against Pinewood on Sept. 12. “[I’m looking forward to] getting more skilled, learning more about my position and also becoming better friends with all of my teammates, Emma said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/DSC_4917-2-1200x795.jpg)

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasnt been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but Ive had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. Theres so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesnt exist, you can build it yourself, Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“Animation just clicked in a way. I had been interested in art, but that felt different. [Animation] felt like it had something behind it, whereas previous things felt surface level. I wasnt making that crazy of things, but just the process of doing it was much more enjoyable, Carter Chadwick (22) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Screen-Shot-2022-08-16-at-9.44.08-AM-900x598.png)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and its played such a major role in who Ive become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something Im [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala (21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

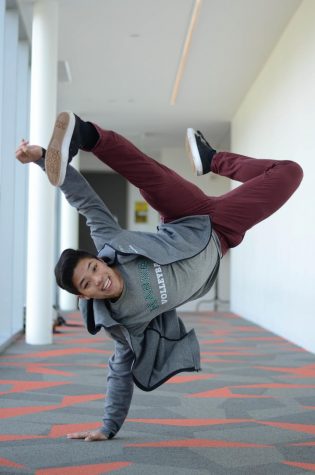

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“Im not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that theres a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyones so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you arent going to get those championships if you arent fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)